It's September, but island beaches from the Aegeans to Zante are still buzzing in Greece. Mykonos has been the summer's Go-To spot for superstars and supermodels; the mainland and cities are also seeing the British and Europeans coming back.

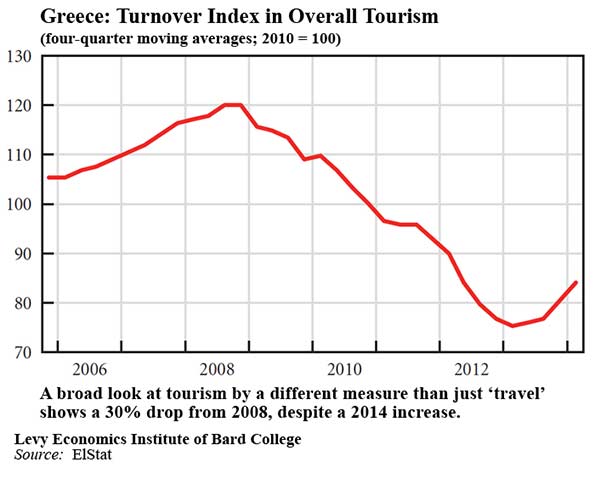

Greece's reemergence on the tourist circuit and the celebrity-watch sites has brought travel revenue, which accounted for 12 billion euros through April, actually above the previous peak in 2008. And, based on arrivals, the national tourism agency predicts that visitors will account for 13 billion euros this year.

So did the appearance of Lindsay Lohan and friends in the Greek isles signify, as one newspaper put it, a template for Greece's economic recovery?

It didn't. It's even still possible that Greece's economic troubles have yet to hit bottom — no one really knows. There is one definite, though. Even with a dramatic increase in its significant tourism industry, the dance floor under Greece's summer parties has been resting on a breathtakingly shaky foundation.

The debt-ridden economy has now endured 24 quarters of negative output. Young Greeks continue to flee, straining the country's pension system.

Extreme austerity regime policies — fiscal tightening — have resulted in the most extreme unemployment rate in Europe, 27 percent.

Private investment remains in a free fall, with a decline of more than 10 percent over 2013. Financial institutions are barely lending. The gross total of doubtful and nonperforming loans by major banks is up from 5 percent to 25 percent since 2010.

And, while tourists are crowing about Greece's fantastic bargains, those low prices are partly a reflection of the salary squeeze on Greek workers. Wage deflation is at a pace never before experienced in a post-WWII era developed country, even as household taxes continue to rise.

Those facts are just shorthand — an almost random selection from the reams of data we've compiled and analyzed at the Levy Economics Institute that document the continued precariousness of the economy.

This isn't the first time in recent months that a seemingly positive sign in Greece has been wrongly celebrated as the start of a recovery. The country's return to the bond markets in April was cheered as the end of a four-year exile. But the exercise was a public relations play. Demand for the bonds reflected the state of excess global liquidity, not investor confidence in Greece as a good risk. (Not to mention that the bonds were implicitly guaranteed by the European Central Bank.)

The improvement in tourism isn't a sham like the bond market show. It's real — but it's such a small portion of the overall picture that it's having only a minimal impact on the terrible employment problem, and on Greece's balance of payments.

Millions of tourists may keep landing at Greece's airports. I hope they do. But don't expect ordinary Greeks to be planning their own luxury vacations anytime soon.

Dimitri Papadimitriou is president of the Levy Economics Institute of Bard College. The publications, conferences, workshops and congressional testimony of the institute have a wide international audience.

Flickr photo by efilpera: Clouds over Mykonos, September 2014.