Paul Krugman got it right. But it should not have taken a Nobel Laureate to note that the emperor's nakedness with respect to the connection between the housing bubble and more restrictive land use regulation.

A just published piece by the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston, however, shows that much of the economics fraternity still does not "get it." In Reasonable People Did Disagree: Optimism and Pessimism About the U.S. Housing Market Before the Crash, Kristopher S. Gerardi, Christopher L. Foote and Paul S. Willen conclude that it was reasonable for economists to have missed the bubble.

Misconstruing Las Vegas and Phoenix: They fault Krugman for making the bubble/land regulation connection by noting that the "places in the United States where the housing market most resembled a bubble were Phoenix and Las Vegas," noting that both urban areas have "an abundance of surrounding land on which to accommodate new construction" (Note 1).

An abundance of land is of little use when it cannot be built upon. This is illustrated by Portland, Oregon, which is surrounded by such an "abundance of land." Yet over a decade planning authorities have been content to preside over a 60 percent increase in house prices relative to incomes, while severely limiting the land that could have been used to maintain housing affordability. The impact is clearly illustrated by the 90 percent drop in unimproved land value that occurs virtually across the street at Portland's urban growth boundary.

Building is largely impossible on the "abundance of land" surrounding Las Vegas and Phoenix. Las Vegas and Phoenix have virtual urban growth boundaries, formed by encircling federal and state lands. These are fairly tight boundaries, especially in view of the huge growth these areas have experienced. There are programs to auction off some of this land to developers and the price escalation during the bubble in the two metropolitan areas shows how a scarcity of land from government ownership produces the same higher prices as an urban growth boundary

Like Paul Krugman, banker Doug French got it right. In a late 2002 article for the Nevada Policy Research Institute, French noted the huge increases auction prices, characterized the federal government as hording its land and suggested that median house prices could reach $280,000 by the end of the decade. Actually, they reached $320,000 well before that (and then collapsed).

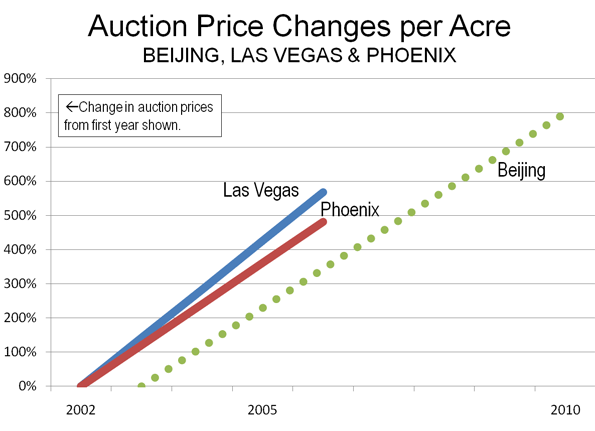

In Las Vegas, house prices escalated approximately 85% relative to incomes between 2002 and 2006. Coincidentally, over the same period, federal government land auctions prices for urban fringe land rose from a modest $50,000 per acre in 2001-2, to $229,000 in 2003-4 and $284,000 at the peak of the housing bubble (2005-6). Similarly, Phoenix house prices rose nearly as much as Las Vegas, while the rate of increase per acre in Phoenix land auctions rose nearly as much as in Las Vegas.

In both cases, prices per acre rose at approximately the same annual rate as in Beijing, which some consider to have the world's largest housing bubble. According to Joseph Gyourko of Wharton, along with Jing Wu and Yongheng Deng Beijing prices rose 800 percent from 2003 to 2008 (Figure). This is true even thought we are not experiencing the epochal shift to big urban areas now going on in China.

The Issue is Land Supply: The escalation of new house prices during the bubble occurred virtually all in non-construction costs such as the costs of land and any additional regulatory costs. It is not sufficient to look at a large supply of new housing (as the Boston Fed researchers do) and conclude that regulation has not taken its toll. The principal damage done by more restrictive land regulation comes from limiting the supply of land, which drives its price up and thereby the price of houses. In some places where there was substantial building, restrictive land use regulations also skewed the market strongly in favor of sellers. This dampening of supply in the face of demand drove land prices up hugely, even before the speculators descended to drive the prices even higher. Florida and interior California metropolitan areas (such as Sacramento and Riverside-San Bernardino) are examples of this.

Missing Obvious Signs: There are at least two reasons why much of the economics profession missed the bubble.

(1) Unlike Paul Krugman, many economists failed to look below the national data. As Krugman showed, there were huge variations in house price trends between the nation's metropolitan areas. National averages mean little unless there is little variation. Yet most of the economists couldn't be bothered to look below the national averages.

(2) Most economists failed to note the huge structural imbalances that had occurred in the distorted housing markets relative to historic norms. Since World War II, the Median Multiple, the median house price divided by the median household income, has been 3.0 or less in most US metropolitan markets. Between 1950 and 2000, the Median Multiple reached as high as 6.1 in a single metropolitan area among today's 50 largest, in a single year (San Jose in 1990, see Note 2). In 2001, however, two metropolitan areas reached that level, a figure that rose to 9 in 2006 and 2007. The Median Multiple reached unprecedented and stratospheric levels in of 10 or more in Los Angeles, San Francisco, San Diego and San Jose- all of which have very restrictive land use and have had relatively little building. This historical anomaly should have been a very large red flag.

In contrast, the Median Multiple remained at or below 3.0 in a number of high growth markets, such as Atlanta, Dallas-Fort Worth and Houston and other markets throughout the bubble.. Even with strong housing growth, prices remained affordable where there was less restrictive land use regulation.

Seeing the Signs: Krugman, for his part, takes a well deserved victory lap in a New York Times blog entitled "Wrong to be Right," deferring to Yves Smith at nakedcapitalism.com who had this to say about the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston research:

It is truly astonishing to watch how determined the economics orthodoxy is to defend its inexcusable, economy-wrecking performance in the run up to the financial crisis. Most people who preside over disasters, say from a boating accident or the failure of a venture, spend considerable amounts of time in review of what happened and self-recrimination. Yet policy-making economists have not only seemed constitutionally unable to recognize that their programs resulted in widespread damage, but to add insult to injury, they insist that they really didn’t do anything wrong.

Maybe we should have known better: beware economists bearing the moment’s conventional wisdom.

------

Note 1: The authors cite work by Albert Saiz of Wharton to suggest an association between geographical constraints and house price increases in metropolitan areas. The Saiz constraint, however, looks at a potential development area 50 kilometers from the metropolitan center (7,850 square kilometers). This seems to be a far too large area to have a material price impact in most metropolitan areas. For example, in Portland, the strongly enforced urban growth boundary (which would have a similar theoretical impact on prices) was associated with virtually no increase in house prices until the developable land inside the boundary fell to less than 100 square kilometers (early 1990s). A far more remote geographical barrier, such as the foothills of Mount Hood, can have no meaningful impact in this environment.

Note 2: William Fischel of Dartmouth has shown how the implementation of land use controls in California metropolitan areas coincided with the rise of house prices beyond historic national levels. As late as 1970, house prices in California were little different than in the rest of the nation.

Wendell Cox is a Visiting Professor, Conservatoire National des Arts et Metiers, Paris and the author of “War on the Dream: How Anti-Sprawl Policy Threatens the Quality of Life”

Photograph: $575,000 house in Los Angeles (2006), Photograph by author

ridiculous

Hey Wendell, if building is largely impossible, how did clark county manage to add 260,000 housing units from the early-mid 2000s? Just to put this in perspective, there are 292,000 units in suffolk county, MA -- that is, the city of boston. So essentially, they added almost an entire city of boston in a city where it is "largely impossible" to build. Sorry, no "victory lap" for paul k...

Land Use Policy vs. Lending Standards?

Seems to me that in most cases many feel the need to explain the housing market collapse as a black and white situation; its got to be the fault of either the mortgage industry (and its political affiliates) or those presiding over land use regulatory power. The debate certainly provides for some good rhetoric, but rarely links each together.

Let's face it - many of the mortgage products being pushed to just about anyone with a pulse would have never come to exist were it not for the extreme under supply of housing in many of the nation's growth poles. And I think most would agree those shortages were a direct result of land use policies that - in some form or another - restricted the supply of entitled land or the rate of delivery of new housing product.

Don't get me wrong, I am all for the intended purposes of growth restrictions - preservation of important natural amenities/resources, lower public infrastructure costs, and the list goes on and on. However, I believe the controlled experiments we have coined as "smart growth" have failed. Time to try a different approach.

Furthermore, local land use policies are not geographically isolated (as some would argue). What has come to be the norm in California, for example, clearly affects the Phoenix and Las Vegas housing markets. Households and employers do have the choice to leave exorbitantly high cost locations. And if and when a significant number of them do...they put strong upward pressure on other markets. For that reason I don't think anyone can point to Phoenix or Las Vegas as arguments against the linkage between land use restrictions and the housing bubble. If more housing was permitted to be built in California during the past decade...do you really think prices in Phoenix or Las Vegas would have ramped up so dramatically??? I doubt it.

More houses in Vegas and Phoenix

I am an avid reader of New Geography, but claim no expertise in these issues - just an interested layman.

That said, a couple of things just don't connect for me in this analysis. And for the sake of transparency, while I allow for land use policies as a factor in local prices and local boom/bust cycles, it seems pretty apparent to me that both in the markets you cite (Vegas and Phoenix) and nationally, the most recent crash had much more to do with lending practices and speculation.

First, it seems far-fetched to believe that these two cities would have been spared the national housing crash with looser building policies. And if so, the only thing that looser building policies during the boom would have gifted us with here in 2010 would be more housing inventory in these two markets. How is that a good thing?

Second, do you believe that availability of land is the only constraint on building in the Southwestern desert? How about water? Non-renewable aquifiers are diminishing; river supplies are over-subscribed and snow pack may well be in long-term decline.

I suspect we are of different idealogical bents, but I find it hard to believe many people can visit the greater Phoenix area and conclude that the main thing it suffers from is a surfeit of land use restrictions.

Check out the Williamson Act

Check out the Williamson Act of 1965 (please take note of the Act's year, thank you):

http://www.conservation.ca.gov/DLRP/lca/Pages/Index.aspx

In addition to what I've posted below, the artificial scarcity of land for housing and development in ALL areas of California was *intentional* due to pressures brought to bear upon politicians and planning agencies by members of the "Conservation Movement" which later morphed into the "Environmental Movement."

One example is the Theodore Payne Foundation and the Sierra Club purchasing large tracts of land adjacent to Hwy 138 through the west-end of the Mojave Desert. The State of CA tried to widen this highway (aka: "Blood Alley") due to the many crash-related deaths that took place each and every year simply because the road usage had increased with population growth in my State.

Highway 138 serves as a metropolitan bypass route of sorts as well as an alternate route to Highway 395 and Freeway 15 to Las Vegas.

The State was blocked for many years due to "Conservation" groups and then later "Environmental" groups buying up land to thwart highway safety measures such as widening the highway by one lane in each direction. Their excuse was some random small lizard of non-descript character and so each group sought to block development out of spite for the rest of the populace.

To this very day, only a portion of this deadly highway has been widened - the rest is "locked up" by private purchase as described above.

The "Eco" Movement has A LOT of blood on its hands for what they have done.

These movements' early adherents consisted of young adults in the 1960's who were influenced by Rachel Carson's "Silent Spring."

Code words for artificial land scarcity:

"open space"

"green belt"

"common areas"

"community space"

"nature preserve"

"open space preserve"

"open-access public space"

Note the collectivist terminology used in these code words.

~Misstrial

4th Generation Californian

Need to learn basic structural urban economics

The current confusion in the United States about the cause of housing bubbles is truly remarkable.

It is well understood within Australia and New Zealand now - even dare I say it within the economics profession - that artificial regulatory fringe urban scarcities are the problem.

Mike Insulmann of Metrostudy in the United States explained this extremely well at a recent Real Estate Editors Conference in Texas. As Mr Insulmann clearly stated, it takes a "scarcity trigger" to get housing bubbles underway and finance is simply the fuel. Equity, bubble equity or mortgage debt - it doesnt much matter. It's not mortgage debt fueling China's bubble for example.

I highlighted Mike Insulmann statements within a Scoop NZ article "Americans slow learners about housing bubbles".

Americans obviously need to be reminded that Texas is still part of the Union. Why aren't we seeing delegations of public officials and others from the US bubble markets visiting Texas to see what they are doing right?

On my website Welcome Page I provide a definition of an affordable housing market. Just follow the numbers for individual bubble markets, by checking out if there are artificial regulatory scarcity values on the fringes. If there are - its a bubble market.

Mr Cox within his excellent article above has clarified the "fringe scarcity value" situation with respect to Phoenix and Las Vegas - something a number of economists who should know better, have made confusing public statements about.

Unless the real cause of these unnecessary housing bubbles is correctly understood, real solutions cannot be put in place. The great mystery is why there has not been a constructive public conversation on these issues in California in particular. After all - this State triggered the Global Financial Crisis.

Hugh Pavletich

Performance Urban Planning

www.PerformanceUrbanPlanning.org

Christchurch

New Zealand

Krugman's point is misunderstood.

Krugman's said that some areas of the country were more vulnerable to housing bubbles because a variety of factors make it more difficult to build there. In his words:

"...in the Zoned Zone, which lies along the coasts, a combination of high population density and land-use restrictions - hence "zoned" - makes it hard to build new houses. So when people become willing to spend more on houses, say because of a fall in mortgage rates, some houses get built, but the prices of existing houses also go up. And if people think that prices will continue to rise, they become willing to spend even more, driving prices still higher, and so on. In other words, the Zoned Zone is prone to housing bubbles."

His point was that the Fed should have recognized the bubble and taken action to curb the excesses in the financial system. If you read his columns and his blog, he makes this point again and again:

http://krugman.blogs.nytimes.com/2010/01/06/bernanke-and-the-bubble/

http://krugman.blogs.nytimes.com/2010/01/04/bernanke-in-atlanta/

http://krugman.blogs.nytimes.com/2010/01/12/bubble-denial-2/

http://krugman.blogs.nytimes.com/2008/12/23/bubble-blindness/

In other words, Krugman points the finger at the Greenspan Fed, not at land use regulations, for essentially ignoring the bubble and instability in the financial system.

So does Krugman think we should have fewer land use regulations to prevent housing bubbles? I'll let him answer that:

"Oh, and someone will surely raise the claim that this shows that you mustn’t have “smart growth” policies because they cause housing bubbles. Can I say that this is deeply stupid? On one side, we’re supposed to believe that markets are efficient and wonderful; on the other, we’re supposed to believe that anything which constrains buildable land — which, you know, sometimes happens for entirely natural reasons — will send markets into wild irrational swings. Those poor, fragile, omnipotent markets, able to handle anything except mild government intervention …"

For the rest, read here: http://krugman.blogs.nytimes.com/2010/01/06/desert-bubbles/

Agreeing with Krugman with a Qualification

Peter...

Thank you for your comment.

Krugman's point is really no different than mine. The first cause of the housing bubble was clearly laxity in the financial markets (as I have said for years, see, for example, my 2007 open letter to the Bank for International Settlements: http://demographia.com/db-bis.pdf). The metropolitan areas with stronger land restrictions were more vulnerable to bubbles. The bubble occurred only where there was strong land use regulation.

The mortgage losses were concentrated in these metropolitan areas. Without the strong land use regulations, the extraordinary price escalation in these markets might not have occurred and the losses would have been less intense. All of this might have made it possible to avoid the Great Recession, or softened it considerably.

The subject of my article was the Boston Federal Reserve paper that specifically criticizes Krugman on his position that the housing bubble was limited to metropolitan areas with strong land use restrictions. The Boston Fed was wrong, as Las Vegas and Phoenix, the two metropolitan areas used in the criticism have most of their "abundant land" for development behind the virtual urban growth boundaries of government owned land.

My perspective on smart growth is different from Krugman's. Smart growth has been broadly associated with higher house prices in a broad range of economic literature and this association is not circumscribed to bubble environments (for references, see: http://demographia.com/db-dhi-econ.pdf). All things being equal, prices will be driven up where the demand for housing exceeds the supply of affordable land on which to build housing.

My interest is that US households should enjoy the best standard of living possible. That begins with housing affordability. Median Multiples (median house price divided by median household income) that are materially above the 3.0 norm have occurred only where there is more restrictive land use regulation (before, during and after the bubble). If housing costs more than necessary, then households have less to spend on other goods and services. As a result, they have a lower standard of living. In word, this is immoral.

Best regards,

Wendell Cox

Demographia

www.demographia.com

On the contrary...

I have no doubt that the bubble was nation-wide. I live in California and grew up and moved from the Southeast with family members in TN, NC, and GA. I moved to CA in 2000, at which point there had already been the beginning of a bust in the dot-com bubble. Afterward there was a mad rush for "safe" investments and that was determined to be real estate.

Some have made these wild claims that there was no bubble in such places as TN, GA, and TX. But there are many factors that determine a bubble, one of which is the rapid rise in real estate prices. For example, when I left home, you could seriously buy a house for $40,000. Within a few years the same type of houses were going for $75,000 and at the height of the boom they were going for $120,000 or so. That sounds like chump change to people from the coasts but percentage wise represents a tripling in value. This was especially true in places like Atlanta where many of the lower income areas saw marked appreciation during the bubble. If Atlanta wasn't a bubble city then how come it suffers from one of the worse foreclosure rates in the country? Its all a matter of perspective and the so-called "cheap" cities didn't escape the fallout. Sure- some might be doing better than others. But the housing bubble was indeed nation-wide.

Does this clarify things for you, TX1234?

TX1234, your anecdotal evidence is contrary to the statistical evidence collated by people like Wendell Cox and Robert Shiller.

Look at THIS graph for a real eyefull:

http://www.newgeography.com/content/00500-case-shiller-index-housing-pri...

It is important to concentrate on "median multiples" when analysing and comparing housing affordability. Here is where I think your anecdotal analysis is misleading:

1) Prices of existing property in rapidly growing jurisdictions DO rise on account of their convenient location relative to the expanding urban fringe. (Sometimes called "Ricardian rents").

2) The LOCATION of the low-price options you describe merely shifts a few miles from where you knew they were originally located.

3)Incomes also rise in rapidly growing jurisdictions. This is why prices could rise due to "location" advantage, and "average prices" for the jurisdiction rise, yet the median multiple could remain roughly the same.

What happened in these jurisdictions was nothing remotely comparable to California and the other land-restricted bubble jurisdictions. Again, look at Robert Shiller's graph.

Atlanta, Georgia, is a special case. How much do you know about the "Community Reinvestment Act"? THIS guy predicted way back in 2000, what the results would be:

http://www.city-journal.org/html/10_1_the_trillion_dollar.html

Atlanta is "ground zero" for this stuff.

The bright side for Atlanta is that property prices remained so low thanks to low regulation of supply, that the amounts of money lost by the financial system on these defaults, is a miniscule fraction of what has been lost through the California insanity. In California, we are talking about millions of "million-dollar mortgages". In Atlanta we are talking about a million or so $40,000 - $100,000 mortgages.

Land Use Restrictions = High Home Prices

I figured out long ago that once local and State-wide land use regulations including "green belt" and "nature preserve" requirements were enacted by the 60's Leftist crowd, that it would be highly unlikely I would ever be able to buy a home since prices would endlessly rise due to an enforced and intentional scarcity.

Further, NIMBY's are none other than the 60's Baby Boomer group who determined to enforce population and land development controls for their financial and marxist ideological benefit.

They succeeded in this endeavor due to the support they received from politicians, Planning Commissions, and Land Use agencies such as LAFCO in Los Angeles County. These agencies benefited from higher and higher developer fees and building fees that were passed on to new home buyers. Mello-Roos taxes are another one.

Existing property owners benefited from ever spiraling upwards home "values" which they understood to be a source of wealth, thus contributing to the mindset that "saving is for losers" and other thought-forms that discouraged thrift and saving money which actually strengthens our nation's financial security.

Only now with the downward move of residential real estate prices, have I a chance of purchasing a home here in California.

~Misstrial

4th Generation Californian