There are two key lessons that the US can learn, from the competition amongst European countries to attract knowledge-intensive jobs. One lesson is that it is possible to encourage the growth of knowledge-intensive jobs in regional clusters. Another is that while several high tax European countries have fallen behind the competition for knowledge-intensive jobs, Sweden and other Nordic nations combine high taxes with strong concentration of knowledge-intensive jobs. Nordic countries also have the best ability to attract investment capital into start-ups, despite high taxes.

A key reason for this success is a smart tax policy, through which funds from a successful investment in one company may be invested in new companies, and taxation applies first when the gains are realized. Also, Sweden is among European countries that have abolished taxation of wealth and inheritance – which has limited effect on the tax base but makes the country significantly more attractive for entrepreneurs and investors. The European experience might provide useful insights for US policymakers, which face the challenge of fostering knowledge-intensive jobs in a time when there is a push for increasing private-sector tax revenues.

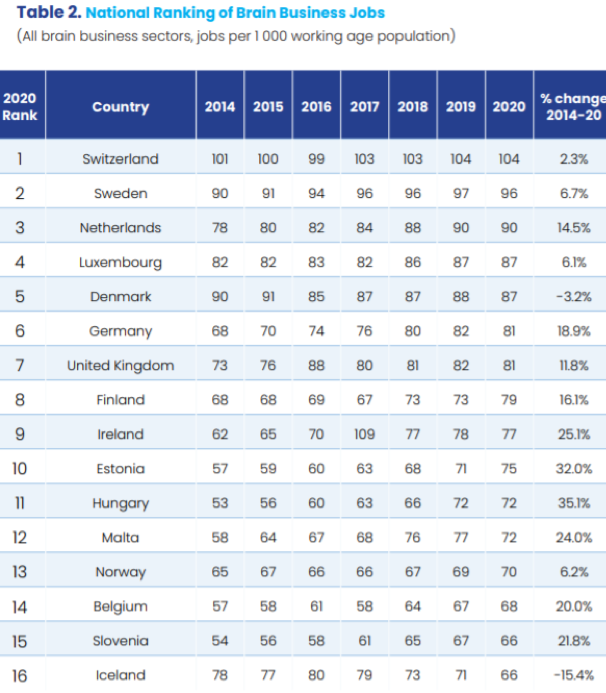

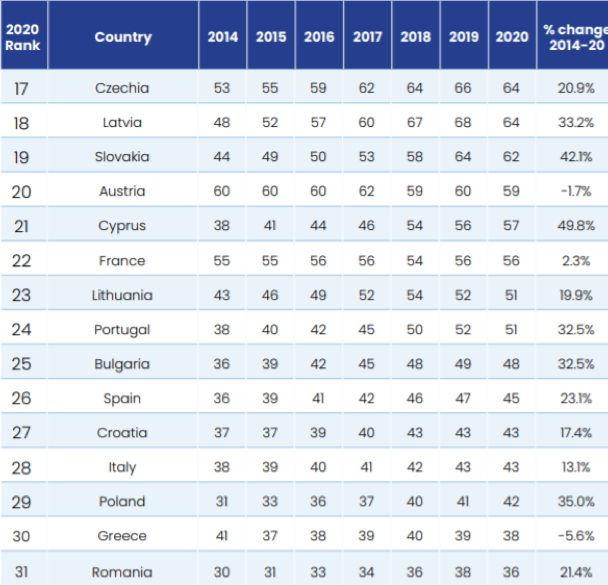

The European Centre for Entrepreneurship and Policy Reform (ECEPR) has in collaboration with Nordic Capital, a leading Nordic private equity firm, for the fifth year in a row mapped the knowledge-intensive jobs of Europe through the Brain Business Jobs Index. As we have previously written in New Geography, geographical equalization of knowledge-intensive jobs is a strong trend in Europe. Growth is particularly strong in Eastern and Central Europe, and some Southern European nations.

A challenge for US innovation is that, while many of today’s large companies grew from small operations set up in garages of Silicon Valley, prices there have risen so much that young entrepreneurs often cannot even rent a garage. Developed innovation regions such as New York, Los Angeles, and San Francisco attract many young talents. Yet, the cost of living is so high that even some young talents hired by tech companies have a strained economic situation. A similar situation exists in Europe, with regions such as London and Paris having many brain business jobs, but relatively stagnant development. Growth is instead occurring in lower-cost regions that have a good talent supply.

Knowledge-intensive firms in expensive European regions often focus on climbing the value chain and outsourcing new jobs, such as programming, to Eastern European capital regions. Southern Europe is also benefiting from this shift. Countries such as Portugal, which previously had low concentrations of knowledge-intensive work, are increasingly attracting young global nomads with programming skills, who appreciate the many sun hours and low cost of living.

We believe there are two key policy lessons for the US, from the European development of knowledge-intensive jobs. One is the opportunity to encourage growth of knowledge-intensive jobs in regional clusters, an already ongoing trend in the US. Perhaps a more important challenge is how the US can maintain the growth of knowledge-jobs, while business taxes may be raised. In Europe, some high-tax countries have fallen behind the race. France, Austria, Belgium, and Norway already have a lower share of their working-age population employed in knowledge-intensive businesses than Estonia and Hungary.

Out of 31 European countries, France ranks at 22nd place when it comes to the share of the share of working age population employed in highly knowledge intensive sectors. Only 5.6 percent of the French working age population is employed in such sectors, and the rate of growth is best described as stagnant. Between 2014 and 2020, brain business jobs concentration grew with as little as 2 percent in France.

Cyprus currently has surpassed France, with 5.7 percent working in brain business jobs - an increase of 50 percent since 2014. Austria ranks slightly above Cyprus, with 5.9 percent of working age population employed in highly knowledge intensive companies. But there is no growth happening in Austria, which in fact has lost 2 percent of the highly knowledge intensive jobs since 2014. In Slovakia, as comparison, the growth during the same period has been 42 percent. Currently 6.2 percent of the population of this former communist country is employed in brain business jobs, outpacing Austria.

Estonia, a country whose economy was in shambles when the Soviet Union collapsed some three decades ago, is the Eastern European country which has highest concentration of knowledge-intensive jobs. Since 2014, the rate of change has been 32 percent, and currently 7.5 percent of the Estonian population is employed in brain business jobs. The capital of Estonia, Tallin, is a small city - yet an innovative IT-hub.

Clearly, much of the growth is happening in up-coming nations that combine lower cost of talent with overall lower tax rates. Yet, Sweden next to Switzerland has the second-highest concentration of knowledge-intensive jobs in Europe, despite relatively high taxes. Sweden has fully 9.6 percent of its working age population employed in highly knowledge intensive jobs. And while the rate of increase since 2014 is just below 7 percent, it is a relatively ok development for a country with already high level of development.

The Nordic region was the only greater region of Europe that managed to add brain business jobs even during the 2020 pandemic-year. A possible explanation is that Nordic firms have good access to growth capital. In the 2021 brain business jobs index, we find that the average highly ranked innovation firm in Nordic brain business regions attracted 85 million Euros in investment. This is far higher than 35 million in Western Europe, 23 in Southern Europe and 10 in Eastern Europe.

Higher levels of taxation have been, and continue to pose, a challenge for countries such as Sweden. But the level of taxation is not the only factor that matters. Tax revenues are 24.5 percent of US GDP, according to the OECD, considerably lower than 42.9 percent in Sweden. Yet Sweden has neither wealth nor inheritance tax. Sweden also has tax participation exemption for capital gains and dividends from investments in unlisted assets, including start-ups. Proceeds from a successful investment in one company may be invested in new companies through a holding company, i.e. “recycled”, without triggering any tax payment. Taxation only applies when the gains are extracted from the holding company to the individual owner(s). Taxes always matter, particularly so for high-risk investments. But with a smart tax design, even high-tax countries can attract innovation capital.

Dr. Nima Sanandaji is the Director of European Centre for Policy Reform and Entrepreneurship (ECEPR). He has written more than a hundred policy papers on subjects ranging from integration and womens career progress to the changing geography of successful enterprise and the future of jobs. His work, which includes 18 books, has been quoted in media around the world and translated to several languages.

Klas Tikkanen is the chief operating officer of Nordic Capital. Previously, he was a management consultant with McKinsey & Company, followed 19 years working in senior management functions, mostly as a chief financial officer in private equity or bank-owned portfolio companies.

Photo: TechCrunch via Flickr under CC 2.0 License.