South Florida connotes a certain lifestyle in media and popular culture. Miami’s bright, tall energy has always been intertwined with the Florida Everglades’ quiet, flat landscape – low, grassy plains soaked with swamp water and edged by dense jungle. The seam where these two opposites meet is neither active nor passive; it is, instead, a third thing, where man’s activity has subtly modified the landscape, and nature has slowed man’s pace closer to its own. The edge of the Everglades has an almost off-kilter Caribbean or Central American sense of place that feels exotic and familiar at the same time. Its pleasant tension reassures me there is still an edge to Florida, when the scratchy blanket of protective regulation is thrown off to reveal informal, naturalized structures that blend beautifully into the natural environment.

Southwest of Miami lies the city of Homestead, Florida, famous for being the front door through which Hurricane Andrew entered Florida in 1992. Today, Homestead is an exurb of Miami, with a relentless street grid extending west and south. Homestead’s housing, schools, and commercial strips grew after Andrew’s devastation, ending only at the hard edge of the Everglades National Park.

Along this line, the housing and farmland stops, and is taken over by the wide 'River of Grass' –the term of the writer Marjory Stoneman Douglas, which has come to be synonymous with the Everglades' ecosystems of marshes, swamps, mangrove forests, rocky land, and marine environments. Douglas, as well as local writers Patrick Smith and Carl Hiassen, has brought this unique place to life, with vivid descriptions of the colorful, offbeat character of the people who seem attracted to its vastness, and the freshwater river under it that flows down to the Caribbean Sea.

Homestead’s western frontier is a jagged edge, a squared-off, pixilated curve defined by a patchwork of rear property lines and rural roads. On one side, houses pop up in between rows of beans; on the other, there grows a green a jumble of ficus and palmetto. At more than one location abandoned asphalt strips crumble into the jungle’s interior, a subdivision extended a little too far. Here, no one ever built a home, and the empty lots pass into a suburban archeology of rusted street signs and vine-choked fire hydrants, a developer’s dream faded away.

In the agricultural areas, open fields with crops alternate with tropical fruit groves. Mango, papaya, banana, and coconut bloom in the spring, their fragrant scents wafting in the early morning air. Workers in the field are dwarfed by the flat landscape, a world away from the America’s eighth largest metropolitan area.

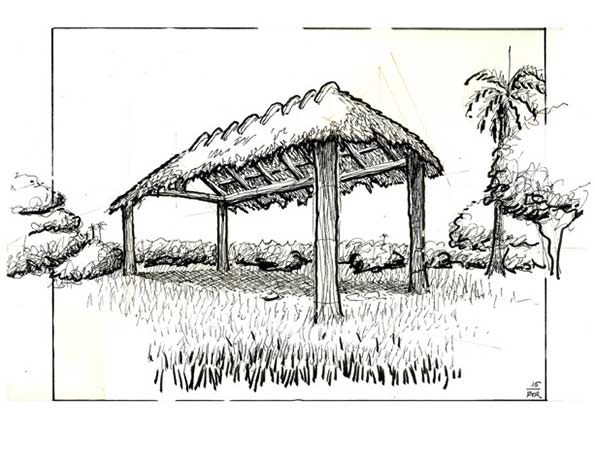

Here, the vernacular building style is a colorful, deliciously un-Miami-like mix of shipping containers and barn tin. The traditional Seminole chickee —a rough, open hut with a raised floor, on a log frame — lends a tropical, exotic flair to this spotty rim of human inhabitation, pressed against nature’s vast size. The chickee's thatched palm fronds create a natural insulation barrier that blocks the sun’s heat, and the fully open sides allow the tiniest of breezes to move air through the space underneath. This native response to the land is more appropriate than the thick-walled, stucco-buttered architecture imported from arid Spain and grafted onto Florida’s humid, wet character. The Seminole answer was to work with nature, have a light touch, and when a hurricane blows it all away, build it again. The classic Florida Chickee is an informal structure that the Seminole tribe builds. Some still use as living quarters in a way similar to camping (for those who prefer air conditioning, power, and plumbing, a more modern house is used).This zen approach to fulfilling the human need for shelter is decidedly un-modern and soft, and the chickee presence at the edge of the Everglades lends a certain amount of respect to the power of nature just beyond.

Civilized life is stripped away, layer by layer, on the margin of the city. Abandoned subdivisions and Native American chickees coexist together, creating a sense of place that overlays the premodern chickee onto the failed subdivisions of modernity. This sense of place tends to mark man’s over-reach into the wilderness. Yet another marker can be found on buildings constructed by modern means, where layers of veneer have not been added: raw materials, unpainted and unadorned, stand crude and timeless against the trees and the sky. The edge’s presence can be sensed where structures start to dissolve into informality.

Everglades National Park is a hard, urban boundary on the map, but on the ground it is a blurred zone where the slow-moving river of grass influences human activities. The nuanced edge continues into the Everglades themselves, where Florida’s subtle water-nature is uninterrupted. Water flows in a gentle, slow sheet across Florida’s flat limestone bed, coated with organic material barely thick enough for life to cling to. Where the limestone base dips a few inches, grass fails to grow; where a nub rises a few inches above this hard plain, unique tree islands gather. These islands are too densely vegetated to admit any human. Their edges are wrapped in a thick tangle of branches and leaves, a sort of bonsai-forest in miniature. Insects, birds, and other small creatures inhabit these infrastructures, forming their own natural urban civilizations of city-states, out of man’s reach.

In between approaching jets and the distant rumble of airboats, a larger silence takes over. Penetrating the membrane between inside and outside gives us a new perspective. To confine our efforts to areas that are already strongly modified by human activities suddenly makes philosophical sense. Boundaries, once created, harden over time, and the softness of the western edge of humanity against the eastern boundary of the Everglades seems destined to harden. In its current state, this snapshot of the feathered, nuanced edge of civilization seems to be delicately balanced between the rural and the natural. Agricultural industry on the periphery of the great conurbation of Miami moves at a pace that is in between the seasonal flow of the Everglades and the nanosecond street culture of contemporary western civilization.

Florida’s ubiquitous industry, tourism, mixes with agriculture even here at the edge of the wetlands, with the airboat rides, fruit stands, and alligator wrestling shows that pepper it. The vernacular architecture of the Everglades is not quite agricultural, yet not quite contemporary Florida either. Its flavor is connected to the Caribbean tropicalism one finds on islands like Puerto Rico, Barbados, and Hispañola. Endlessly adaptable shipping containers sit cheek-by-jowl with chicken coops and thatch awnings to create an ad hoc pedestrian space under palm trees. All is a little too clean and, well, 'inspected,' to be really offshore. But it’s also a little more relaxed than the uptight, postmodern built environment we’ve come to expect in America.

Heading east out of the Everglades is a somewhat wistful journey forward in time. Rural roads lined with mango trees abruptly give way to fruit processing plants, which back up to grocery store strips, and the standard parade of global brand names enters the windshield, a gateway back into contemporary America. Stoplights take longer, the traffic pace quickens, and today’s Florida, like a hair shirt, envelops you in a cocoon of highly regulated infrastructure, put there for your own protection.

Richard Reep is an architect with VOA Associates, Inc. who has designed award-winning urban mixed-use and hospitality projects. His work has been featured domestically and internationally for the last thirty years. An Adjunct Professor for the Environmental and Growth Studies Department at Rollins College, he teaches urban design and sustainable development; he is also president of the Orlando Foundation for Architecture. Reep resides in Winter Park, Florida with his family.

Photos by the author: (top) vernacular building style on the edge of the Everglades; early morning workers arrive in Homestead by bus; protypical Chickee hut; unpainted structure, common on the edge of the Everglades.