For many years, critics of the suburban lifestyles that most Americans (not to mention Europeans, Japanese, Canadians and Australians) prefer have claimed that high-density housing is under-supplied by the market. This based on an implication that the people increasingly seek to abandon detached suburban housing for higher density multi-family housing.

The Suburbs: Slums of the Future?

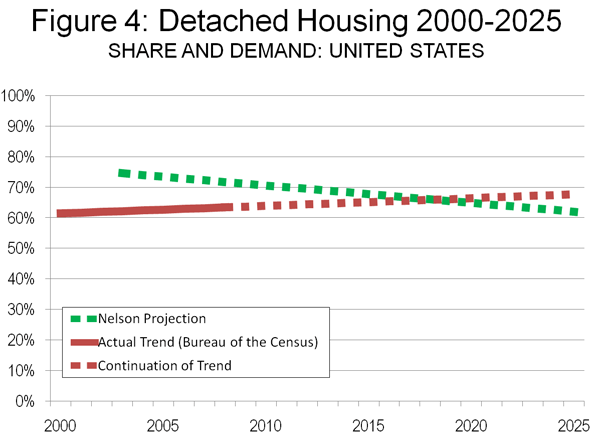

The University of Utah's Arthur C. (Chris) Nelson, indicated in an article (entitled "Leadership in a New Era") in the Journal of the American Planning Association. that in 2003, 75% of the housing stock was detached and 25% was attached, including townhouses, apartments, and condominiums. By 2025 he predicts that only 62% of consumer will favor detached homes, (Note 1). He also predicts a major shift in consumer preferences from housing on large lots (defined as greater than 1/6th of an acre) to smaller lots (Note 2). This, he suggests, would create a surplus of 22 million detached houses on large lots.

This predication is largely made on the basis of "stated preference" surveys which the author, Dr. Emil Malizia of the University of North Carolina (commenting on the article in the same issue), and others indicate may not accurately reflect the choices that consumers will actually make. Dr. Nelson's article has been widely quoted, both in the popular press and in academic circles. It has led some well-respected figures such as urbanist and developer Christopher Leinberger to suggest in an Atlantic Monthly article that "many low-density suburbs and McMansion subdivisions, including some that are lovely and affluent today, may become what inner cities became in the 1960s and ’70s—slums characterized by poverty, crime, and decay."

The Condo Market Goes Crazy

Misleading ideas sometimes have bad consequences. The notion that suburbanites were afflicted with urban envy led many developers to throw up high-rise condominiums in urban districts across the country. Sadly for these developers, the Suburban Exodus never materialized, never occurred. As a result, developers have lost hundreds of millions, if not billions of dollars and taxpayers or holders of publicly issued bonds could be left "holding the bag" (see discussion of Portland, below).

This weakness has been seen even in the nation's strongest condominium market, New York City, where one developer offered to pay purchaser's mortgages, condominium fees and real estate taxes for a year as well as closing costs.

But the damage is arguably worse in other major markets which lack the amenities and advantages of New York.

Take, for example, Raleigh (North Carolina), where low density living is the rule (the Raleigh urban area is less dense than Atlanta). The News and Observer reports that the largest downtown condominium building (the Hue) "considered a bold symbol of downtown Raleigh's revitalization," has closed its sales office and halted all marketing efforts. The development’s offer of a free washing machine, dryer, refrigerator, and parking space were not enough to entice suburbanites away from the neighborhoods they were said to be so eager to leave.

This is not an isolated instance. Around the nation, condominium prices have been reduced steeply to attract buyers. New buildings have gone rental, because no one wanted to buy them. Other buildings have been foreclosed upon by banks; and units have been auctioned. Planned developments have been put on indefinite hold or cancelled.

Miami: Of Little Dubai and Cadavers

Miami’s core neighborhood (downtown and Brickell, immediately to the south) has experienced one of the nation's most robust condominium building booms. More than 22,000 condominium high rise units were built between 2003 and 2008. Miami could well have more 50-plus story condominium towers than any place outside Dubai.

As a result, Miami has suffered perhaps the most severe condominium bust in the nation. According to National Association of Realtors data, the median condominium price in the Miami metropolitan area has dropped 75% from peak levels (2007, 2nd Quarter). By comparison, the detached housing decline in the metropolitan area was 50%; the greatest detached housing price decreases among major metropolitan areas were from 52% to 58% (Riverside-San Bernardino, Sacramento, San Francisco and Phoenix).

The most recent report by the Miami Downtown Development Authority indicates that 7,000 units still remain unsold. The Brickell area is home to the greatest concentration and largest buildings and has the highest ratio of unsold units at 40%.

Icon Brickell (see photograph above) may be the largest development in the core. Icon Brickell consists of three towers, at 58, 58 and 50 floors and a total of nearly 1,800 units. Despite opening in 2008 and offering discounts of up to 50%, barely one-third (approximately 620) of the units have been sold, according to the Daily Business Review, which also reported on May 13 that the developer had transferred control of two of the towers to construction lenders.

One building, Paramount Bay, was referred to by The New York Times as a "47-story steel and glass cadaver" with a lobby "like a mortuary." A real estate site indicates that only one of the buildings 350 units has been sold.

More recently sales have inched up in the core but due not to any suburban exodus. According to The Miami Herald, huge discounts that have lured Europeans, Canadians, and Latin Americans to the core. The real estate and consulting firm Condo Vultures notes that more than 1,000 of the sales are to a few bulk buyers, a market segment some might refer to as "speculators."

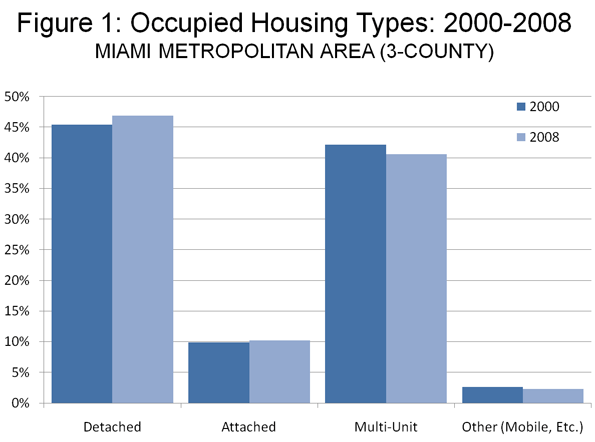

The latest data from the US Bureau of the Census confirms that there is no fundamental shift away from detached housing in the Miami area, as housing trends point toward more detached housing. In 2000, 48.1% of residents in the Miami metropolitan area lived in detached housing. By 2008, the figure had risen to 49.2% (Figure 1). Essentially, the Suburban Exodus remains a mirage.

Portland: Gift Certificates for Distressed Developers

If developer greed was the motive in Miami, government subsidies have been the driving force in Portland. The city of Portland will soon have issued nearly $450 million in urban renewal bonds, provides 10-year tax property tax forgiveness, and reduced development fees, which the Portland Development Commission (PDC) has called "gift certificates" for developers (Note 3).

Gift certificates have not been enough to cure Portland's sickly downtown condominium market. The Oregonian reported that prices were down, on average, 30% over the year ended the first quarter of 2010. Remarkably prices in the much ballyhooed Pearl District are plummeting even more than those in the rest of the Portland area. According to DQ News, the median sale price of a house in the Pearl District dropped four times the average in Multnomah County and an even greater six times decline relative to suburban counties over the past year.

There is more. Just this year, the Pearl District has seen its Eddie Bauer, Adidas, and Puma stores close.

One condominium building the Encore, is reported to have sold only 17 of 177 units. A recent auction of units at the largest building in the city, the John Ross brought prices "far below the replacement cost" according to The Oregonian's Ryan Frank, who noted that "it will likely be years before there’s a new high-rise condo built." Late last year, the Pearl District's Waterfront Pearl was reported to have sold only 31% of its units and had not sold a unit for a year.

The Portland Development Commission itself has become part of the condominium bust story. PDC had indicated it was considering relocating its offices to a new 32-story mixed use tower (Park Avenue West), which was to have included condominiums, offices, and retail stores. For more than a year, the proposed 32-story tower has been an unsightly hole in the ground, with construction suspended. PDC decided to stay put in its older, less expensive offices. Even before PDC decided not to locate in Park Avenue West, the developers eliminated the plans for 10 floors of condominiums, doubtless because it made no economic sense to add to an already flooded market.

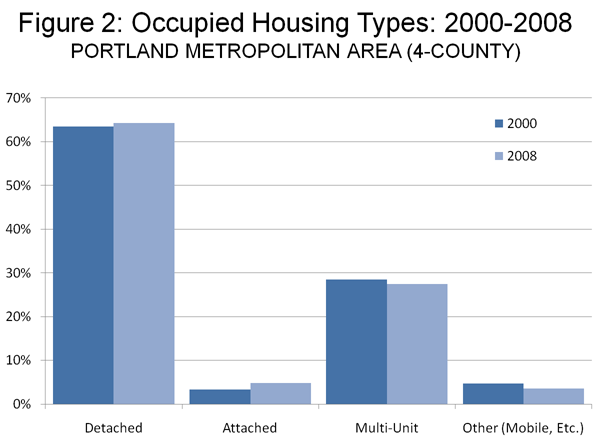

In Portland, like in Miami, the fact remains that suburbia has not been abandoned. Despite the high density over-building in the Pearl District and elsewhere in the core, detached housing has become even more popular in the region. According to data from the Bureau of the Census, the share of households living in detached housing in the Portland metropolitan area rose from 63.7% in 2000 to 64.5% in 2008 (Figure 2).

High-Rise Condos: Slums of the Future?

To say that the high-rise condominium market has fallen on hard times would be an understatement. The condo bust in New York has become so acute that Right to the City, a coalition of community organizations has called upon "the City to acquire the tax delinquent buildings through tax foreclosure and convert vacant units into permanently affordable housing for low-income New Yorkers." In a report entitled People without Homes and Homes without People: A Count of Vacant Condos in Select NYC Neighborhoods, Right to the City points out that there are more than 4,000 empty condo units in 138 buildings, with owners delinquent on nearly $4 million in taxes to the city.

Owners of new condominiums around the nation who paid pre-bust prices for their units may not be inclined to stay around if they are surrounded by less affluent renters who have been attracted by desperate building owners and lenders.

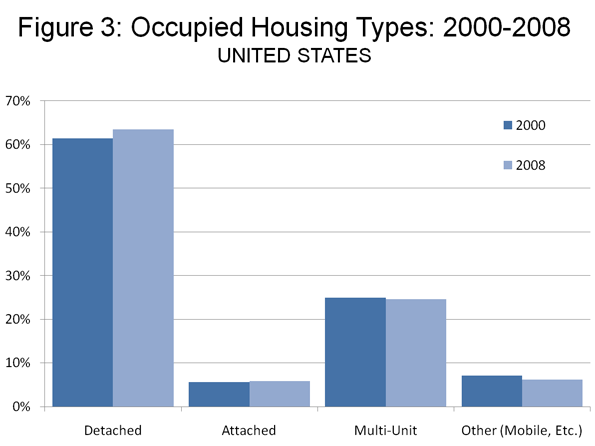

Are these dark towers of discounting the slums of tomorrow? Only the data and time will tell and it's too early to know, but preliminary findings show little of the predicted shift toward higher density living (Figure 3). Certainly national data indicates, if anything, a slightly strengthening market for detached, rather than attached housing (Figure 4).

• Between 2000 and 2008, the share of households living in detached housing rose from 61.4% to 63.5%.

• A similar trend is shown by the national building permits data. Between 2000 and 2009, 75.2% of residential building permits in the United States were for detached housing. This is up strongly from 69.6% in the 1990s and nearly equals the highest on record (the 1960s), when 77.7% of residential building permits (housing units) were detached houses.

Looking at the data, there remains little evidence that the stated preferences on which the predictions relied have been translated into the reality of a shift in preferences toward smaller lots in cores or inner ring suburbs. Domestic migration continues to be strongly away from core counties to more suburban counties. Core cities are growing less quickly than suburban areas. Exurban areas are growing faster than central areas, including inner suburbs.

Clearly, the Suburban Exodus has not begun and there is little reason to believe that it will anytime soon.

Note 1: In estimating the 2003 share of detached housing (75%), Dr. Nelson uses "one-unit structures" data from the 2003 American Housing Survey Table 2-3. US Bureau of the Census American Housing Survey personnel responded to my request for clarification, indicating that "one-unit structures" includes ... single detached housing units, mobile homes, and single attached housing units (such as a townhouse)." Thus the 75% detached estimate is high because it includes mobile homes and single attached housing. As is indicated above, data from the US Bureau of the Census data indicates that the share of detached housing of detached plus attached housing in 2000 was 61.4%. This figure, coincidentally, is virtually the same as the 62% Dr. Nelson predicts for 2025.

Note 2: The assumption that consumers prefer small lot detached housing may not be sufficiently robust and may even be exaggerated. Dr. Nelson appears to principally rely on research by Myers and Gearin (2001) (in the journal Housing Policy Debate) for concluding that consumers prefer small lot rather than larger lot detached housing, defining small lot development as 1/6th of an acre or less or less than 7,000 square feet. Yet neither figure appears in Myers and Gearin. Moreover, a National Association of Home Builders commenter (also in Housing Policy Debate) questions how its data was characterized by Myers and Gearin in justifying a finding of preference for smaller lots (the survey is unpublished). Without access to the original surveys referenced in Myers and Gearin, it is impossible to judge what respondents may have had in mind as the dividing line between large lots and small lots.

Note 3: This characterization was on the Portland Development Commission website (accessed January 2, 2007). It was cited in our report, Zero Sum Game: The Austin Streetcar and Development and subsequently removed from the website. A large share of Portland's urban renewal bonds are insured by Ambac Financial Corporation, which has reported losses exceeding $1 billion in the last two quarters. Ambac indicated that it has "insufficient capital to finance its debt service and operating expense requirements beyond the second quarter of 2011 and may need to seek bankruptcy protection." Ambac was the insurer of State of Nevada bonds to build the Las Vegas Monorail, which has already entered bankruptcy and is unable to pay its bonds.

Wendell Cox is a Visiting Professor, Conservatoire National des Arts et Metiers, Paris. He was born in Los Angeles and was appointed to three terms on the Los Angeles County Transportation Commission by Mayor Tom Bradley. He is the author of "War on the Dream: How Anti-Sprawl Policy Threatens the Quality of Life.”

Photo: Icon Brickell, Miami

emoney

There's also a website dedicated to the series and all of the latest news surrounding it, Sugar Plum Ballerinas, which may be found here emoney

Thomson Three

recent bank jobs also called for the involvement of clerks to detect initial stages of finance fraud through the use of specific software technology or copyrighted tools within the Finance institution Thomson Three

That is very interesting

That is very interesting Smile I love reading and I am always searching for informative information like this. This is exactly what I was looking for. Thanks for sharing this great article.Chatrandom.com

Long on data, short on argument

This is a masterful example of using irrelevant and cherry-picked data to back into a desired conclusion. The claim Mr. Cox would like to refute is that consumer preference will shift away from low-density detached living towards higher-density urban lifestyles. Interestingly, he mentions that stated preference surveys (in scare quotes, of course) actually do indicate that the market for higher-density urban living is under-supplied relative to demand. The Urban Land Institute, a developer trade association whose ultimate interest is in following the market, pretty much agrees.

But rather than spend time confronting the findings of these studies head-on, Cox instead tries to refute them by citing the poor performance of central city hi-rise condos. He leads with the following sentence: “The notion that suburbanites were afflicted with urban envy led many developers to throw up high-rise condominiums in urban districts across the country”. This dramatically overstates the ambitions of condo developers (a very difficult thing to do). Developers never intended for their product to compete head-on with the suburbs. To do that, they would have had to market to families with children, which they recognized would have been foolish – the high-rise lifestyle is something that very few families want, as we would all agree. Instead they pursued two small, but growing markets: unmarried singles/couples and empty-nesters. All the evidence, even the articles that Mr. Cox himself links to but does not refute, establishes that these households have a much greater preference for condo living than family households, which will likely continue to prefer single-family dwellings.

The problems in the urban condo market, then, have very little to do with a failure to lure suburban families to the cities. They were products of a credit bubble and expectations of continued employment growth in city-based industries (i.e. finance).

This bubble, of course, affected every part of the country, and every property type to one degree or another. But in forwarding his anti-urban agenda, Mr. Cox completely fails to provide this context. William Lucy in his recent book Foreclosing the Dream, studies foreclosure patterns in the largest 35 metro areas and finds that foreclosures usually emanate outwards. While some urban neighborhoods certainly suffered (typically ones that were already very poor), it has been newer suburbs and exurbs that were hit the hardest (The book is based on a paper available here http://www.virginia.edu/uvatoday/pdf/foreclosures_2009.doc). DC is a representative metro area, where prices declines got progressively steeper the further out you move from the core ( http://thecityfix.com/moving-through-the-recession-part-5-are-exurbs-sti...). And, for every anecdote of a failed condo project, you can find five stories of ghost town suburban subdivisions and abandoned suburban retail centers.

Using the state of the condo market to gauge demand for urban living is deeply misleading in another important way: High-rise condos represent only a small portion of total housing stock in most cities. Far more common in dense urban areas are single-family attached homes (rowhomes), low-rise apartments, and yes, even detached homes. Take the Boston metro area, for example. Somerville, an independent city on the north side of the Charles River, is actually denser than the City of Boston proper, at over 18,000 people per square mile. In its density, land use patterns, and transportation, it is thoroughly urban, at least by American standards. Yet its bread-and-butter house form is the detached two-family house, which can yield a density of more than 20 units/acre. There are only a handful of apartment buildings in the entire city. By focusing on condos and ignoring the housing stock that actually exists in the urban neighborhoods of places like Somerville, it is impossible to get a true picture of demand for urban lifestyles. Taking a more inclusive view, these urban neighborhoods and inner suburbs have performed much better through the bubble than farther-out suburbs.

The data on housing type trends is also of little use in gauging demand for city living, for the simple reason that, in housing markets, supply is very slow to respond to demand. This is in large part due to long-standing zoning restrictions, suburban transportation networks that can’t handle density, entrenched NIMBY attitudes towards new growth, and institutional inertia on the part of government officials, financiers, and conventional developers who are comfortable with the well-worn business model. The point of the research done by Nelson, Lucy, and the ULI, among others, is that getting our development industry to meet where the market is going, given these hurdles, will be a very difficult task. It's especially difficult when someone’s idea of a fair-minded discussion consists of gleefully recounting failed condo projects.

Getting a handle on unintended consequences

EPar, You make some important points that I really expect people like Wendell Cox to provide the answer to.

Your analysis does attempt to get below the surface statistics, but where you need to further progress with your analysis, is in the vast difference between urban markets with tight controls and high land prices, and with relaxed controls and low land prices.

The connection between urban growth boundaries and housing bubbles has been so conclusively made now, that it is mystifying why it is taking so long for this realization to become "mainstream". The smartest speculators on Wall Street, such as John Paulson, Steve Eisman, and Kyle Bass, were concentrating their "derivatives" based shorting of markets, on mortgages in the growth limited areas - way back in 2006 and 2007. They made around a billion dollars each out of this.

These guys "got it" before the bubbles burst; most others still have not "got it" 2 years after.

In markets like Houston, there was no bubble and no crash. But furthermore, ironically, low land prices meant that inner city redevelopment was able to be aimed at low-price buyers and tenants. The reason for the predominance of high priced Condos in tightly controlled land markets, is simply that only wealthy people could afford ANY homes that were going to be offered, given that the land was so inflated in price. This is also why the intended "densification" is actually hindered, not helped, by tight urban limits.

Meanwhile, lower income people are forced by rising land prices, into long commutes from the "least unaffordable" options out near the urban limits - but even these are several times as expensive as their Houston equivalent. THIS is why foreclosures end up concentrated around these areas. The reason for fewer foreclosures being in the inner city condo market, is simply that there was few of these anyway and the buyers of them tend to be well-off and with stable high incomes.

To study this phenomenon, you need to plot a few charts, for low land value jurisdictions and for high land value jurisdictions. You need to plot the value of land, at the urban limits, and rising towards the urban center; and then plot the value of existing houses and structures on this land; then plot the combined values. Then; you need to plot the values of potential redevelopments at higher density and the ultimate prices for which they will have to sell. Do this, and it will hit you in the face, why urban densities end up higher than normal TOWARDS THE URBAN LIMITS (not in the inner areas) in jurisdictions where land prices are forced up by urban limits.

This is just another lesson in "unintended consequences" of regulation of the kind that Milton Friedman and Friedrich Hayek delighted in telling us.

growth controls & the bubble

Restrictive zoning has many undesirable consequences, but the financial crisis was not one of them. The relationship between price declines and land use regulations is very loose. Just look at the Case-Shiller Index peak-to-trough prices for the top 20 metro areas (http://calculatedriskimages.blogspot.com/2010/05/case-shiller-house-pric...) and match up those markets with their land use regulations as described in Brookings "From Traditional to Reformed" report. Las Vegas and Phoenix were relatively permissive and had the largest declines; Boston and Denver have heavy regs and saw some of the smallest declines. And yes, the anti-planning Texas markets declined the least. Then again, Seattle and Portland with their much-loathed UGB's had declines towards the modest end of the spectrum. All this says is that there were other, much more important factors.

Put simply, zoning & growth boundaries explain rising prices over long periods. They don't explain prices that doubled & tripled in 5 years and then crashed, as happened in the worst markets. The only thing that explains it is speculative demand fueled by cheap credit and unsustainable mortgage products.

I find it funny that over

I find it funny that over the past 4-5 years there have been numerous stories floating around about the coming collapse of suburban America- that somehow all of those people who moved away from the cities are foolhardy and living an unsustainable lifestyle.

There's somewhat of a self-righteous tone to that argument. My take is that those hip urbanites might seek justification for paying out the wazoo for staying in their more densely populated, often expensive urban environments. All I can say is that if the suburbs are supposedly on a downward trend then the current numbers don't show it. For the last several new home reports the results show the most robust activity happening in the Southeast. A region that is currently experiencing rapid economic and infrastructural growth. Last year Pulte Homes bought Centex. Primarily because Centex owns large quantities of land in North Carolina and Texas- two states with the fastest growing populations.

I think this shows that the equation for determining what people prefer and where growth tends to happen. The bottom line is that most Americans prefer single family homes. Secondly they also prefer homes that are within financial reach.

Bob, you gotta extend your time horizon a bit.

It's not that you're wrong here, but I'm worried your critique here might be mischaracterizing the argument regarding the sustainability of suburbia.

I'll ignore our factual dispute on the numbers (which I'd argue do show it) and just suggest that few making the argument that suburbia is going to collapse expect it to be visible in "the current numbers." Nor do they expect us to be able to evaluate their argument over the next 4-5 years. I don't know any self-respecting urban planning theorist who expects the total collapse of the suburban lifestyle in the next 4-5 years. I know few who expect it in the next 20. (Perhaps I need to speak with more hyperbolic urban planners or something.)

But if the costs of oil are to increase considerably, and our government loses the ability to continue to subsidize the cheap loans, road maintenance, and massive urban services infrastructure required to make suburbia work, things will gradually change. Suburbia--and the many economic subsidies that supply it and make it "within financial reach"--took almost a century to install. So trying to evaluate its collapse on a five-year timescale is like predicting winter won't come based on one sunny day in early November.

Even that being said, I think few expect suburbia to collapse in the real estate market and everyone's tastes to just shift to condos tomorrow. What is expected is the gradual increasing of costs associated with continuing suburban development: taxes on existing properties, the cost of expanding public infrastructure, the costs of driving, the increased difficulty of getting energy from the ground, rising deficits to meet these obligations, yet more demands for home loan subsidies, etcetera. Suburbia might stay cheap and keep getting developed while all these other things just keep ratcheting up, slowly but surely.

In other words, I guess the critique of suburbia's sustainability is based less on the price of housing and the short-term economics of the real estate market and more what's going on everywhere else to keep suburbia in business.

It's same here in Dallas

Mr. Cox's descriptions of vacant towers and shuttered businesses resemble what has gone here in many of the high-density projects initiated in the last few years in and around downtown Dallas. One high-profile office building-turned-condo tower is now offering rentals. Another brand new Philip Stark-designed condo tower with over 120 units has only 4 tenants. The newly planned district in which it is located,Victory, is an agglomeration of modern towers with vacant storefronts at ground level as far as the eye can see. It's evident that its developer, Ross Perot Jr., mad a foolish bet in believing that people want to be able to walk to work. That is, if only the alternative of a huge house on cheap but expansive land didn't seem so enticing.

I write more about the ghost-town that Victory Park in Dallas has become at my blog, as well as how some suburbanites would rather seek entertainment close to home:

http://architectureandmorality.blogspot.com/2009/06/empty-victory-when-u...

The inevitable growth of suburbia

Mr Cox sets out clearly why the suburbs will thrive for the foreseeable future.

There are two major issues those advocating core residential developments persistently fail to mention.

Firstly, the construction costs of large inner city residential developments cost well in excess of twice as much per square ft to construct than stand alone residential housing in suburbia.

Secondly, provided serviced lots are available on the fringes, new residential development has the capacity to respond quickly to increased market demand. On the other hand, the larger and more costly inner city residential developments take years to plan and develop.

As Mr Cox's article illustrates, these large and often hugely expensive inner city developments too often are completed when the market sours. The risks to developers and their financiers are enormous.