A couple weeks ago I outlined how the Ohio River Bridges Project in Louisville had gone from tragedy to farce. Basically none of the traffic assumptions from the Environmental Impact Statements that got the project approved are true anymore. According to the investment grade toll study recently performed to set toll rates and sell bonds, total cross river traffic will be 78,000 cars (21.5%) less than projected in the original FEIS. What’s more, tolls badly distort the distribution of traffic that will come such that the I-65 downtown bridge, which is being doubled in capacity, will never carry just what the existing bridge carries right now anytime during the study period, and won’t exceed the design capacity even slightly until 2050. Meanwhile, the I-64 bridge that will remain free will grow in traffic by 55% by 2030, when it will be 34% over capacity.

A nearly identical scenario is playing out in Portland with the $2.75 billion I-5 Columbia River Crossing. Joe Cortright of Impresa consulting unearthed the information through freedom of information requests looking into the investment grade toll study on that is being conducted for that bridge. You can see his report here (there’s also a summary available).

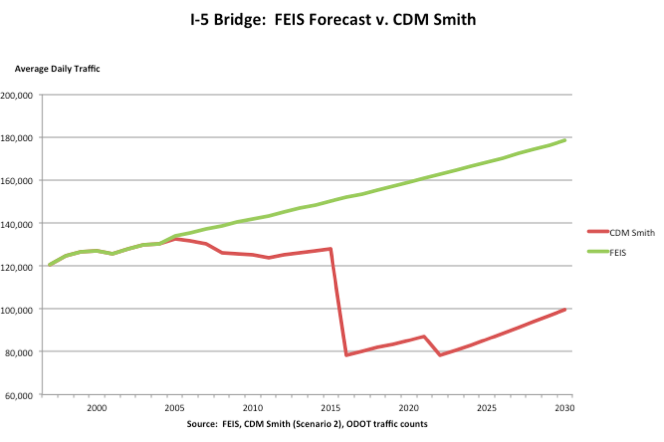

I’ll highlight some of his truly eye-popping findings. Traffic forecasts are inflated, of course. The toll study is suggesting traffic increases of 1.1% to 1.2% per year when over the last decade traffic has actually declined by 0.2% per year on average even though there are no tolls. But it’s the addition of tolls that badly distort cross-river traffic and make a mockery out of the EIS. Here’s the money chart for the I-5 bridge itself:

How is it possible that after building a gigantic multi-billion dollar bridge traffic declines? For the same reason as Louisville: tolling will cause huge amounts of traffic to divert to the I-205 free bridge. By 2016 traffic on I-205 would rise from 140,000 per day to 188,000 – and up to 210,000 by 2022 (full capacity).

This is so eerily similar to the Louisville situation, that someone suggested, only half in jest I suspect, that they must be having “how to” training sessions on this stuff over at AASHTO HQ.

Unlike Louisville, where a docile press is basically in cahoots with the state DOTs pushing the project, Portland’s media started asking questions. And one local paper even caught a civil engineering professor from Georgia serving on the independent review board for the project labeling the tolling scheme “stupid.” (Louisvillians take note).

Oregon DOT director Matt Garrett released a letter in response in which he says, “This work is fundamentally different than the traffic analysis completed for the Final Environmental Impact Statement, and with very different goals in mind.” I agree. The FEIS was performed with the goal of getting this bridge the DOT wanted built approved. The toll study was designed to withstand financial scrutiny on Wall Street and be relied on in selling securities. I’ll let you be the judge of which is more likely to be closer to the truth. What’s more, Cortright addresses this very issue by saying in his report, “Neither federal highway regulations nor federal environmental regulations authorize or direct using multiple, conflicting forecasts for a single project, or using one set of traffic numbers for one purpose, and a different set for another.” I might also add that the DOTs in Louisville have not to the best of my knowledge made similar claims to explain away an identical discrepancy there. Nevertheless, the rest of Garrett’s letter acknowledges that I-5 will see a big traffic drop and there will be diversion from tolling. So he appears to just be doing the bureaucratic equivalent of “pay no attention to that man behind the curtain.”

Again, want to know how it is that we spend so much money on transport infrastructure and get so little value? It’s because far too many of our highway dollars go into boondoggle mega-projects ginned up through political pressure (watch this space as I have another example coming soon) instead of into projects that make transportation sense. It may well be that there are legitimate problems with the existing I-5 river crossing, but these numbers give no confidence that the Oregon DOT has come up with a good or cost-effective plan for dealing with them. Unlike some, I do think we need to build more roads in America. Unfortunately our system is set up to ensure the survival of the unfittest instead of projects that make actual transportation and economic sense.

Aaron M. Renn is an independent writer on urban affairs and the founder of Telestrian, a data analysis and mapping tool. He writes at The Urbanophile, where this piece originally appeared.

Photo of current Columbia River crossing by Jonathan Caves.

Thomas Rubin on the pointless bridge specs

Informative comment from Thomas Rubin recently.

"Unless someone on the inside spills the beans, we’ll never know for sure, but, if you just take a hard look at the Columbia River Crossing (CRC) design, you wonder if there was a deliberate attempt to make the bridges extra expensive to ensure that it could not be financed without tolls.

The best example of this is the lower deck on both spans. These were to be two five lane upper decks for rubber tire transit with lower decks. On the downstream, South-bound one, there would be the two light rail tracks. On the upstream, North-bound one, there was going to be pedestrian and cycle tracks.

Even if, for purposes of this discussion, one accepts that there will be light rail on the bridges, there is absolutely no reason why the pedestrian/cycle tracks could not be put on the same, downstream span, allowing the upstream span to be single deck.

Obviously, this would save a huge amount of money on everything from load to design to materials and labor just from removing the lower deck. However, since the key aspect (which this bridge design failed miserably) was for vertical clearance for shipping on the River, the requirement for a single deck upstream bridge is to match the clearance of the two-deck, downstream bridge. Since the upstream bridge could be single deck, that means that the traffic carrying level on it doesn’t need to be as high as the comparable level on the downstream double-decker. Therefore, measured from the ground-level at the end of this span at each end, the bridge can be shorter because the ramp-ups can begin and end closer to the bridge.

Using conservative estimates, if we assume that this takes fifteen feet off the “road level” and the “top” of the bridge, and a four percent grade (four feet of height gain over 100 feet), that means that the bridge could be approximately 375 feet shorter – at each end.

A bridge that is 15 feet shorter in height and 750 feet shorter in length, can be safely built with lower load-carrying capacity because a one-level, closer-to-the-ground bridge has a lot less mass that needs to be supported than a higher, two-level bridge. This is a massive difference in cost.

The documentation on CRC is massive and I certainly can’t say I’ve seen all of it, or even a significant portion of what has been made public, but I have found absolutely nothing that leads me to believe that there is anything that responds to the key question; in fact, I get the impression that there was a very clear effort to try to keep the key question from being asked.

That question is, what is the cost of putting light rail on CRC?

The real cost, not what is in the EIS or other plans, which were there to justify a large Federal grant for the project, but not so large that it would make it obvious how much the higher cost really is.

There is only real way to do that determination, which is, OK, we have the cost to do CRC with light rail, what would be the cost for a bridge with the same “rubber tire” traffic capacity without light rail?

By the way, if you are talking about a five-lane road bridge, the additional load from pedestrian and/or cycle lanes is very minor. This can be handled easily from what is, in essence, pretty light outboard lanes hung on the main bridge lanes on one or, better, two lanes added on the outsides of one or both spans (assuming that the best design for a non-light-rail crossing would still be two spans, which is a question that should be reconsidered for the design of the alternative). There is, most certainly, absolutely no requirement for a second deck, even assuming that there is a consensus that pedestrian and cycle facilities should be part of the design.

The light rail element was an important limiting factor in the shipping clearance. About the absolute maximum grade that rail can handle is six percent, but you really don’t want to go over four percent for any significant length, particularly if you need to be trying to accelerate up or slowing to a stop near the bottom of the grade. This is compounded by the needs at the Vancouver end, where the train would be street-running through downtown pretty close to the River edge, so it has to get up to the required shipping clearance level from a fairly low start in a relatively short distance of travel. (There could have been other ways around this, such as starting the upward grade earlier on the North shore, but this would have required that the light rail line be elevated through part of the City of Vancouver downtown, which would be both more expensive – which never appeared to be a major concern – and far more of a visual intrusion and a barrier dividing downtown, which, I’m sure, would have generated some negative feedback, on top of all that existed already.)

If we were starting the transportation design from a blank piece of paper, I would have really liked to examine the option of a Busway/HOV/HOT lane. There was what, in my opinion, a very half-assed attempt to pretend that this was being considered as an alternative, but an attempt to do so by good planners and designers who really wanted to do the best design to see what could work could have made a big difference. It is possible that the extra cost of the lane(s) could have been covered by bonding against projected revenues and that the bus service – including direct service to places other than downtown Portland – could have provided far more mobility at lower operating cost.

One interesting factor would be direction of travel. In some cases like this, there is a predominant direction of travel – in this case, I would assume Southbound to Portland in the morning and Northbound to Washington State in the afternoon – and there is the possibility of a switchable lane. Makes it a more challenging design, but certainly far, far, far simpler than putting light rail on CRC.

One problem is that, while there was finally a desire to add capacity over the River, and on the Washington side to some extent, the Oregon side remains dedicated to absolutely no addition to road capacity and certainly not any added freeway lanes. So, Southbound, if you have more capacity over the River, to one extent, what you have accomplished is to move the initial major plug point further South along I-5, etc......"

Free alternative routes and flow changes from new capacity

The point that bond issuers want projects like these is also important. At some stage, investors have to become "once bitten, twice shy" about bonds for tolled road infrastructure projects. I and several transportation economists I know would have told them it wouldn’t work, because they are trying to compete with alternative routes that are still free of charge.

I will explain the extent of the problem; few people, even in the transport sector, understand this.

The graphed relationship between “demand” and “flow”, is a backwards-bending curve. That is, a tipping point in demand is reached when traffic that was flowing at a certain rate, becomes “stop-start”. Suddenly, even though demand has increased, flow has decreased. It is this phenomenon that road planners are fools to allow to happen.

But it has happened – then, bingo, an ignorant private investor builds an alternative toll road. It only needs a few percent of existing users of the congested route, to switch; and suddenly the previously-congested free route, is a free-flow route again, throughputting MORE vehicles at the crucial peak period, than what it was when traffic was “stop-start”.

The trip destinations are on a massive winner – i.e. the businesses and property owners; the toll road investors take a haircut. (I actually like this as a means of the public getting a free new road out of stupid investors).:-) It is actually nonsense to imply as anti-car activists usually do, that the problem is “lack of demand” (this straight after arguing for years that induced traffic will re-congest any expansion in capacity); the throughput of the total system is actually massively increased even though even the old routes APPEAR to be carrying LESS vehicles at peak. They are actually carrying more, but not under the old "stop-start" conditions.

Of course a lot of this is time and route switches, but it is inherently more efficient that people can plan their commute around efficient times of attendance at work, not “beating the traffic”. And the point remains that the car drivers are perfectly happily paying the cost of their car, petrol, repairs, insurance, whatever – adding up to 20 cents a km for an efficient little car; more for bigger ones. They just can’t be bothered paying more to travel on a new toll road that offers less time savings than the stupid private investors thought it would.

The correct time to apply “pricing”, is not when capacity is added sufficient to restore faster FLOW, but when there is stop-start congestion. Once demand has risen again to the point that all routes are congested, turning one lane into a “priced” express lane will achieve impressive results. Such lanes, correctly priced, throughput MORE vehicles than the adjacent free of charge lanes which remain stop-start. Therefore no-one “loses”, because no-one who is “priced out” of the express lane(s) is adding to congestion in the free ones.

If you don’t “get it”, oh well, 99% of people, unfortunately don’t.