The 1990s proved to be quite a nice decade indeed for most of America's largest cities. It was an era of general prosperity in all of America to be sure, but in contrast to previous decades, the turnaround also extended from the suburbs to many of the nation's biggest cities, notably New York, Chicago, Miami, San Francisco and San Jose. The notion – popular in the 70s and 80s – associating cities with a sour and fatalistic sense of decline and dysfunction, or even anarchy, in the 90s finally began to evaporate. There emerged a bracing new sense of optimism that these large cities had found a new role for themselves in the world.

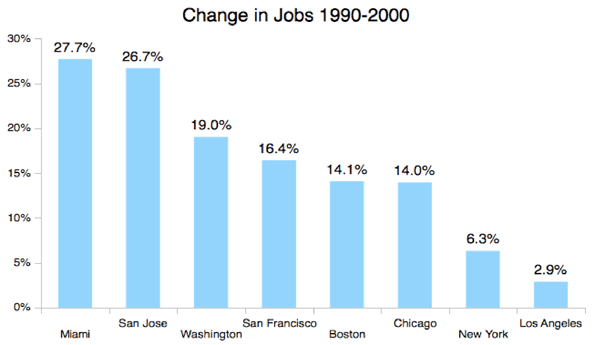

This is evident from the large decreases in crime in these cities where lawlessness once reigned and also from the job numbers from that decade, when all of America's tier one metros added jobs.

Some of these places lagged overall US growth, but considering their lower rate of population growth most of these cities enjoyed robust economies. The aerospace and defense center of Los Angeles, hit hard by the post-Cold War “peace dividend”, and the devastating 1992 riots, was a partial exception.

The 90s saw the convergence of two trends that profoundly benefited these cities: the digitization and globalization of business. The 90s were the heart of the digital revolution. At its beginning, corporate “data processing” was still dominated by mainframes and personal computers were not yet fully deployed even on corporate desktops. By the end of it, the internet was widespread and had caused a business revolution. In the middle were several waves of technology change and disruption: first client/server, then internet based computing, PC and mobile phone ubiquity in business, the Y2K retrofit, and the beginnings of integrated Enterprise Resource Planning systems.

The 90s also saw a lesser known revolution in American business: deregulation and structural changes. In the past many businesses that had previously operated on a local or regional basis – banking, utilities, retail, etc – got rolled up into much larger super-regional, national, and increasingly global players.

These shifts provided big benefits to these tier one cities. Obviously high tech havens like the Bay Area, DC, and Boston did particularly well in this decade. Also performing strongly were professional services hubs like Chicago. These rapid waves of technology and business change created a lot of new openings for professionals to master, not just by creating and implementing technology, but also in adapting business processes to the new realities as well as managing the organizational change journey. These newly rolled up businesses also needed the types of services firepower typically located in larger locales, stimulating further demand. Notably, virtually all of this demand was satisfied with employment growth on shore, much of it in these tier one cities.

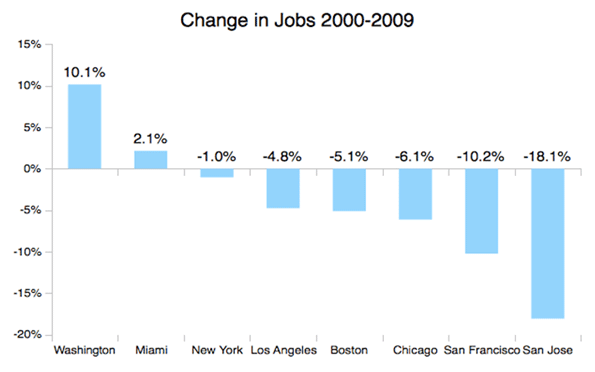

The 2000s, however, were a very different story. This decade began with the dot com bust and its associated recession, a funk from which the Bay Area economy has yet to fully recover despite Silicon Valley's continued reign as high tech capital. Similarly, while specialized professional services still flourish, the more mainline areas, such as IT implementations or business process outsourcing, found themselves under significant pressure as digital business matured.

This caused one commentator to famously declare that “IT Doesn't Matter.” Then the offshore wave, which had been a born in the 1990s, began to suck away services work just as had occurred previously in manufacturing. This included not just low skill business process outsourcing like invoice processing, but also high value IT engineering and other services not dependent on face to face interaction. This, we found out, could be performed by high skill, low cost labor in places like India.

This helped to create a so-called “lost decade” of job creation in the US during the 2000s. The tier one metros, save for recession-proof Washington, fared even worse, losing jobs during the decade.

These are facts and trends that barely impacted the world of urbanists, who continued to act as if nothing had changed. The media, located almost totally in primary cities, bought the message but rarely looked at the basic facts.

As a result, when it comes to thinking about America's big cities, too many people remain stuck in the 90s.

Partially this is understandable. The 2000s saw strong increases in GDP per capita in many of these cities. Also, they experienced huge real estate booms and an associated increase in high end amenities of all kinds: swanky hotels, starchitect buildings, upscale new restaurants and shops, etc. But a lot of this has proved somewhat self-delusional. Like Citigroup CEO Chuck Prince's now infamous statement that “As long as the music is playing, you’ve got to get up and dance,” these cities continued to party like it was 1999 even as their job base continued to erode and the real estate bubble headed for a crash.

Today, as the Great Recession has civic finances in a vice grip, and places like Chicago and Los Angeles face stunning budget shortfalls, people are less sanguine. Advocates for the big city model still refuse to face up to the core problems that face our large cities. The real issue should not be how to restart the condo boom, but how to restore what drove the resurgence of the 90s: job creation. This is a national problem to be sure, but not one that seems to interest most big city advocates. It’s almost as if there's an assumption the jobs will come without working for them. The stimulus and bailout, which helped key urban sectors like green building, university research and public employees, is now running out of steam and political support. In the long run they may have served largely to exacerbate complacency.

So rather than a focus on private sector job growth, many urban boosters have remained free to focus on other things like sustainability and lifestyle enhancers in the assumption they would generate jobs But what if it doesn't work out that way? What if the current economy, unlike those boom years of the 90s, does not generate enough money and employment to support these huge regions?

These cities would be well-advised to go beyond counting skyscrapers, new condo construction, green roofs, and bike share programs. Those things are all good, but basic measures of civic health and dynamism like job growth ultimately underpin those things for the long haul. More than anything, these cities need to be fundamentally focused on their commercial success. Their great challenge is figuring out how to recapture that previous era of job growth, and once again become engines of employment.

Aaron M. Renn is an independent writer on urban affairs based in the Midwest. His writings appear at The Urbanophile.

Photo by Werner Kunz (werkunz1)

I would like to say that

I would like to say that this blog really convinced me to do it! Thanks, very good post.

https://rebelmouse.com/reversemydiseasetodayreviews

Perhaps another challenge to

Perhaps another challenge to major cities is how to make themselves livable again to the middle class. It doesn't matter whether a big city has jobs or not. If all but the wealthiest people can't afford to live there then none of that job creation matters. If anything many major cities in the US have become a playground for the rich.

Well, that is a big aw shit

I am sure that Denver is somewhere in the middle.

Dave Barnes

+1.303.744.9024

A Song by the Same Name

You should really check out the song with the same title as this piece by Moxy Fruvous...