The skyscraper is an American invention. During the first 75 years of their existence, skyscrapers were concentrated in a small area south of 59th Street in Manhattan --- in 1962, only one of the world’s 10 tallest skyscrapers was outside that area (Cleveland’s Terminal Tower). It was not until 1975 that a non-US skyscraper entered the top ten (First Canadian Place in Toronto). But by 2000, six of the top ten were outside the United States, with the two Petronas Towers (Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia) being the tallest in the world (Photo 1). By this time, China had its first supertalls (buildings over 300 meters or 984 feet).

China and "Supertalls"

According to China Daily, “The Chinese mainland has five out of the world's 10 tallest skyscrapers,” and “China also has 678 of the 1,478 skyscrapers worldwide with a height of over 200 meters.” (656 feet), including buildings to be completed by 2022. Meanwhile, only one US skyscraper ranks in the top ten, the New York’s One World Trade Center, at 7th.

Given this dominance, it came as a surprise when the Chinese government announced that no more “Supertalls” would be permitted.

According to Beijing’s Global Times, a “general limit suggests any new skyscrapers higher than 500 meters may be subject to daunting approval processed” Further, The circular noted that if a locality legitimately needs to erect a skyscraper taller than 500 meters, the building's design must pass robust tests to ensure its fire safety standards are sufficient, and that it is earthquake-resistant and energy-saving. Then it needs further reviews by the two relevant ministries.

China and Weird Buildings

Dezeen reported that under the ban "building plagiarism” and “copy cat behavior” is to be strictly prohibited. According to Dezeen the policy seeks to “show the style of the times, and to highlight Chinese characteristics” (our emphasis).

Dezeen points out that “In the past, numerous monuments and buildings constructed in China have been direct replicas of those in Europe. London's Tower Bridge, Paris' Arc de Triomphe, Sydney's Opera House and the Eiffel Tower have all been recreated in the country.”

For some time there have been indications that architectural reform was on the agenda. According to The Wall Street Journal, President Xi said in 2014 that “buildings such as the CCTV headquarters, which is one of Beijing’s most iconic towers and is nicknamed “Big Pants” for its design akin to trousers, should no longer pop up in the city” (Photo 2). At the time, President Xi urged architects not to “engage in weird building”— The Journal continued: “the CCTV tower … has been the brunt of jokes among Chinese netizens for years.”

Earlier, Fast Company had reported that “odd-shaped” buildings would no longer be allowed in China. “Bizarre architecture that is not economical, functional, aesthetically pleasing, or environmentally friendly will be forbidden” according to a government directive.

A Tour of Supertalls in China

A quick tour of supertalls in China follows.

Supertall City: Shenzhen: I visited Hong Kong in 1999, and took a trip on the Kowloon and Canton Railway to Guangzhou. On the way, the train passed the Shun Hing Tower (Photo 3) in Shenzhen, the eighth tallest in the world, This later photo, also shows the KK100 building to the left, which supplanted the Shun Hing Tower as the city’s tallest building for a few years (442 meters or 1,449 feet).

Shenzhen seems likely to be most impacted by the new policy. Shenzhen, a mere fishing village before 1979, was designated as a special economic zone by Deng Xiaoping, who is celebrated by a famous billboard near the Shung Hing Tower (Photo 4), Shenzhen has been the fastest growing city in the history of the world. Just four decades old, the 2020 census counted a population of 17.5 million residents, adding a stunning 7,000,000 since the 2010 census.

Shenzhen has become China’s “supertall” city, boasting, according to Emporis, 16 supertalls. By comparison, Guangzhou has nine supertalls, Hong Kong six, Tianjin six (including Goldin Finance 119, see below), Shanghai five, Chongqing five, and Beijing two.

Shenzhen’s tallest building is the Ping An Finance Center (599 meters, 1,965 feet) and the world’s fifth tallest (Photo 5). It is located adjacent to the Futian high speed rail station, from which trains travel directly to Hong Kong, Guangzhou, Wuhan and Beijing. According to Emporis, Shenzhen has the third most skyscrapers of any city in the world (684), trailing number one Hong Kong (1,912) and New York (843). It is worth noting that Shenzhen itself is less than half as old as the Empire State Building, which was the world’s tallest from 1931 to 1973 (replaced by Chicago’s Sears Tower, now the Willis Tower).

Upon arrival in Guangzhou, I was surprised to see the Citic Tower, 7th tallest in the world (Photo 6, middle), across the plaza from Guangzhou East Railway Station. That tower, then city’s tallest, is now the northern focal point of Zhujiang New Town (Guangzhou’s new central business district). This includes the 8th tallest building, the CTF Tower (Photo 6, left), at 530 meters (1,739 feet) and the 27th tallest Guangzhou International Finance Center. (Photo 6, right) at 439 meters (1,472 feet).To the south, and across the Pearl River (Zhujiang) is the Canton Tower, which is even taller, at 600 meters (1,969 feet), but like other principally observation and television towers, does not meet the definition for inclusion in most tallest building lists (Photo 7).

Shanghai: Greatest Concentration: In Shanghai, three of the world’s tallest buildings are in closer proximity than any other of the world’s tallest buildings. The world’s third tallest (632 meters/2,073 feet), the Shanghai Tower (top photo, left), is directly across the street from the 12th tallest (492 meters/1,614 feet) Shanghai World Finance Center (top photo, right), as well as the 35th tallest (421 meters/1,380 feet) Jin Miao Tower (top photo 7, middle).These three buildings are all located in of Shanghai’s Pudong “Lijiazui” business district (Photo 8, right), across the Huang Pu (river) from the Bund.

Suzhou: First Casualty of the Decree? In Suzhou, which borders Shanghai, the Suzhou IFS Tower is the world’s 21st tallest and located in one of China’s larger edge cities (Photo 9). Across Jinji Lake, there is another edge city, Suzhou Center, with its distinctive “Gate to the East” (Photo 10). There had been plans to build another supertall, the Suzhou Zhongnam Centre, across the street from the Gate to the East that would have been the second tallest in the world. However, the Global Times reported this to be the “first casualty” of the new policy, with its planned height reduced from “729 meters to 499 meters to comply with the new rule.” A photo of the now shelved larger design is here.

Tianjin’s Unfinished Supertall: When on a day trip by train from Nanjing to Harbin in 2014, I looked forward to seeing the Goldin Finance 117 building in Tianjin, and photographed the nearly topped-out tower (Photo 11). But two years later, headed from Shanghai to Changchun (Jilin), there it was again, still unfinished. The building is still not occupied, even though it has reached its maximum height of 597 meters (1,957 feet), which would make it the sixth tallest in the world. Lists of the world’s tallest buildings now tend to ignore it.

Other Examples: The supertalls been built in many other cities of China.For example:

- Wenzhou,in Zhejiang, added a supertall, the Wenzhou World Trade Center (322 meters, 1,056 feet), in 2010 (Photo 12).

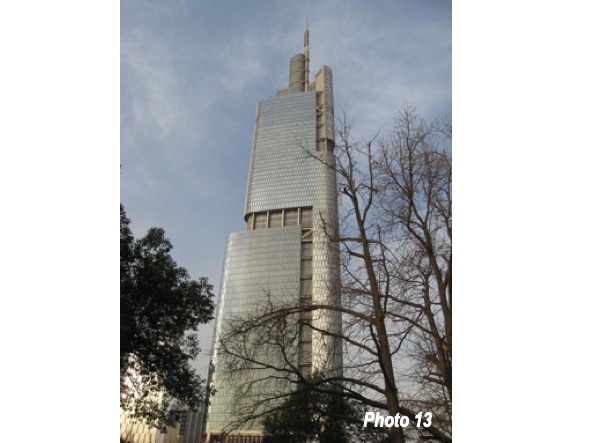

- Nanjing’s concentrated (for China) central business district (see: Downtown China) is crowned by the Zifeng Tower (Photo 13) at 450 meters (1,476 feet).

- One of China’s smaller capitals (Gansu province), Lanzhou, has Honglou Times Square (313 meters or 1,027 feet), nearing completion in this 2018 photo (Photo 14).

The Future of Supertalls

China’s ban is not all of the bad news for supertalls. The Kingdom Tower in Jeddah, planned to replace Dubai’s Burj Khalifa as the world’s tallest building has been suspended after reaching approximately only one-third of its intended height, due to labor issues with a contractor. Moreover, there are no other types of structures so threatened by remote working and fears of continued or future pandemics, which tends to disperse, rather than concentrate employment. On the other hand, a new supertall in Kuala Lumpur, Merdeka 118, is expected to open in 2022 and will displace the Shanghai Tower as the world’s second tallest. It seems likely that supertall stories will be much less about China from now on.

Wendell Cox is principal of Demographia, an international public policy firm located in the St. Louis metropolitan area. He is a founding senior fellow at the Urban Reform Institute, Houston, a Senior Fellow with the Frontier Centre for Public Policy in Winnipeg and a member of the Advisory Board of the Center for Demographics and Policy at Chapman University in Orange, California. He has served as a visiting professor at the Conservatoire National des Arts et Metiers in Paris. His principal interests are economics, poverty alleviation, demographics, urban policy and transport. He is co-author of the annual Demographia International Housing Affordability Survey and author of Demographia World Urban Areas.

Mayor Tom Bradley appointed him to three terms on the Los Angeles County Transportation Commission (1977-1985) and Speaker of the House Newt Gingrich appointed him to the Amtrak Reform Council, to complete the unexpired term of New Jersey Governor Christine Todd Whitman (1999-2002). He is author of War on the Dream: How Anti-Sprawl Policy Threatens the Quality of Life and Toward More Prosperous Cities: A Framing Essay on Urban Areas, Transport, Planning and the Dimensions of Sustainability.

Photograph: Shanghai Tower, Shanghai World Finance Center and Jin Mao Tower in Shanghai. Photos from street between (all photos in article by author).