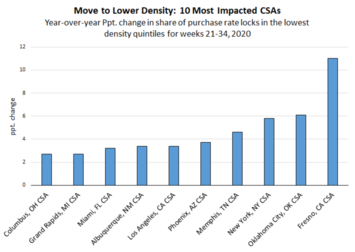

The Great American Land Rush of 2020 is underway in many metro areas across the country. Large numbers of American workers are untethered from a central office. As a result many are moving to less dense areas with less expensive land (and homes) and more of both. The greater New York City and Los Angeles metros are the hardest hit. Take NYC where single-family residential land per acre is 24 times as expensive in the densest quintile of zip codes as compared to the least dense quintile ($3.06 million vs. $129,000). But most large metros are experiencing intra-metro movement to less dense and less expensive areas.

For the first time, we are able to empirically measure this land rush within metro areas by using high frequency loan transaction data combined with land prices at fine levels of geography.

COVID-19 has been the catalyst for this Land Rush. First is the unprecedented shift to working from home. At-home workers are highly educated, with above average incomes and a tendency to live in large, coastal urban areas, especially New York City, Los Angeles, San Francisco, San Jose, Seattle, and Boston. An estimated 42 percent of the 155 million U.S. labor force is working from home full-time during the pandemic, up from 5.2 percent in 2017. Business leaders and employees think increased levels of remote work is here to stay. Post-pandemic, the share of days spent working at home is expected to increase fourfold, from 5 percent to 20 percent. And will likely be even higher in large coastal metros. In a recent survey that asked home buyers what they want, these 6 answers accounted for 90 percent of the responses: more space to work, more space, a bigger yard, more recreational space, more home learning space, and a less expensive home. If working from home is an option: a more spacious, less expensive home on more land and further away from traditional job centers addresses all six.

Second, these same coastal urban areas have benefited from agglomeration benefits due to economies of scale and network effects. Think of it as a gravitational pull that has allowed them to grow bigger and bigger economically. But they are also known for sky high state and local taxes, housing and land costs. These act to counter the favorable gravitational forces and are largely self-inflicted wounds. They are the result of choices made, including excessive land use regulations that make land both expensive and scarce, high public pensions, burdensome business regulations, and in some cases, rent control. As long as employers required knowledge workers to work centrally, these workers (and employers) were willing to put up with being poorly treated.

Decades ago Walter Wriston (Citibank CEO from 1967 to 1984) had this insight: “Capital goes where it’s welcome and stays where it’s well treated.” Areas will find that their financial and human capital will flee if not treated better.

Consider if only 15 percent of households in an area decided to no longer put up with this poor treatment and move. It might be 10, 15, 25, or 50 miles, which would have a large impact on many central cities. Or 200, 500 miles, or a thousand miles, with varying impacts on metros, states, and regions. A move to welcoming places that offer bigger lots and more spacious homes, lower taxes, less crime, and lower density. These areas may not have the same urban amenities as the cities they are leaving, but restaurants, gyms, and coffee shops tend to follow their customers.

Read the rest of this piece at American Enterprise Institute

Tobias Peter is the director of research at the American Enterprise Institute’s Housing Center, where he focuses on housing risk and mortgage markets. Working closely with the director of the AEI Housing Center, Mr. Peter has coauthored a variety of reports on housing policy, specifically on the impact of federal policy on housing demand and homeownership, housing finance risks, and first-time home buyers.

Edward J. Pinto is a resident fellow and the director of the AEI Housing Center at the American Enterprise Institute (AEI). He is currently researching how to increase the entry-level housing supply for first-time buyers and renters who earn hourly wages, as well as examining the current house price boom that began in 2012. This continues his previous work on the role of federal housing policy in the 2008 mortgage and financial crisis.