Tucked away in the bottom corner of the San Francisco Bay, tech royalty make themselves at home in their silicon castles. Santa Clara County is the wealthiest county in California, and 14th in the nation, boasting an average median household income of $96,310. However, where there are kings, there must be subjects. Despite its affluence, Santa Clara remains one of the most unequal counties in the United States. The combined forces of enormous wage gaps, exorbitant housing prices, and shifts in the regional economy have compounded over recent years, resulting in a shrunken middle class and increased poverty levels.

Santa Clara County contains just over 1.9 million people and is home to much of the Silicon Valley. The relatively recent explosion of growth in the high-wage technology industry has generated a new rank of upper-middle class to fabulously wealthy individuals. But, even in the economic miracle that is Silicon Valley, poverty remains a prevalent force and affects a disturbing number of lives in the region. Although, according to the Census Bureau, only 8.3% of Santa Clara County residents live at or below the Federal Poverty Level (FPL), this number drastically underestimates the true number of people that are experiencing financial hardship in the region. In a study conducted by United Way, it was found that the real cost budget for a family of four residing in Santa Clara County stands at $65,380 per year, or 281% of the FPL.

High regional housing costs account for much of the discrepancy in poverty levels between the county and the nation. A study out of the California Budget and Policy Center calculated that the poverty rate in Santa Clara County soars to 18% when factoring in housing costs, meaning nearly one in five residents live in poverty.

It is for this reason that the region has one of the largest homelessness populations in the nation, with around 7,600 homeless individuals residing within Santa Clara County. When local homeless individuals were surveyed regarding obstacles to securing housing, the top four answers were as follows: No job/income, no money for moving costs, bad credit, and lack of available housing. Of course, poverty is cyclical, and these answers affect one another to some extent: a lack of income means no money for moving costs, which may lead to bad credit and which could then lead to an inability to secure permanent housing. Around 56% of survey respondents also reported being homeless for over a year, up significantly from 47% just two years prior, indicating that the homeless in Santa Clara County continue to face significant obstacles to securing housing. High homelessness rates are symptoms of a greater trend: the fact that gross income inequalities in Santa Clara County have created a society of have’s and have not’s, separated by an income gap that shows no sign of closing.

Housing Trends

The most significant impediment to financial security in the county is the volatile housing market and the exorbitant cost of owning a home. According to a report conducted by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development on the South Bay Area, the average price of houses sold in 2014 stood at $788,500 for an existing home and $828,000 for a new home. This is over four times the median value of homes nationally, which stands at $178,600. The disparity is even more prevalent in the areas of the region closer to large technology firms, such as Palo Alto, where the average home costs $2.43 million. San Jose also has the 7th largest share of renters in major U.S. cities, 56 percent, a rate that only continues to increase as housing costs do the same. The median gross rent in Santa Clara County stands at $1705 per month, nearly double the national average.

Current trends indicate that the increasing housing costs show no signs of reversing, which does not bode well for residents that are already struggling financially. A study from the California Budget and Policy Center found that, in 2013, over 50% of households classified as low-income were at risk of moving out of the area due to increased housing costs.

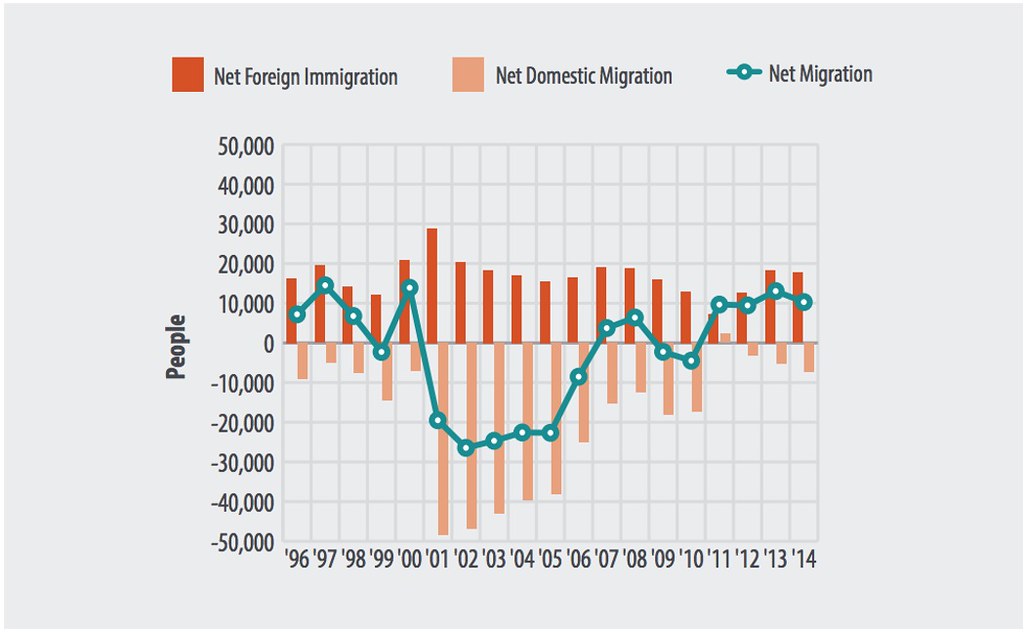

Net domestic migration in Santa Clara County is overwhelmingly negative.

The result of high housing costs? Net domestic migration has been negative every year since 1996, except 2011, and appears to be dipping further, despite the fact that the population of Silicon Valley has grown continually in recent years. This can be attributed to a combination of natural births and massive foreign immigration rather than domestic migration. Therefore, negative net domestic migration suggests that a large portion of residents are leaving the area due to a lack of an income that cannot keep up with rising costs of living.

However, for those who stay, high housing prices lead to a plethora of other disadvantages, creating a cycle of poverty that decreases social mobility in the region. A search for cheaper housing has led many to seek living arrangements in the southern and eastern parts of San Jose, where housing is cheaper, but comes at the cost of higher crime rates and worse school districts. Additionally, job growth has been concentrated in the western parts of the county. The search for cheap housing has led to an increase in overcrowded households, as residents move in with one another in order to share the costs of rent. The Santa Clara County Department of Public Health concluded in 2014 that 14% of residents were living in overcrowded households, with 5% living in severely overcrowded households. Latinos in the region are disproportionately affected, with 31% living in overcrowded households and 12% living in severely overcrowded households.

The combination of these factors limits social mobility by undermining each individual’s access to economic opportunity. Moving into an overcrowded house in an underfunded public school district limits potential to obtain a quality education that may provide access to high-skilled, high-wage jobs.

The Income Gap

Inequality in the region is perpetuated by a growing income gap, and the ardent hunt for afford-able housing may be explained by the gross income disparities among residents. As housing prices have skyrocketed over recent years, incomes simply have not kept up with costs of living, particularly at the lower end of the spectrum.

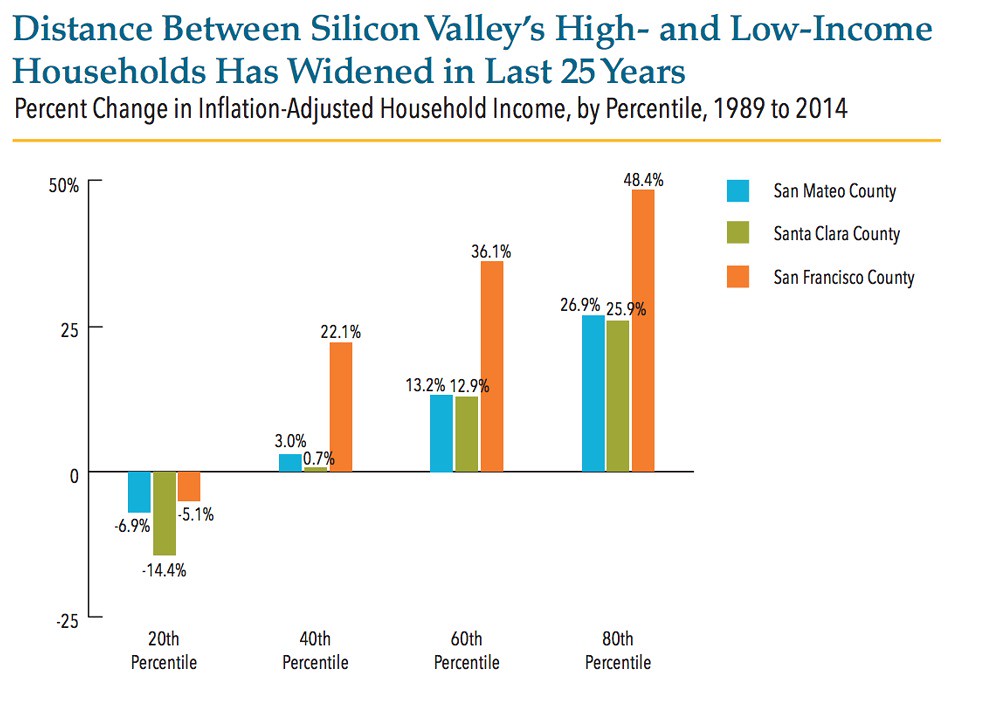

Santa Clara County’s income gap has widened considerably since 1989.

Economic gains in the region have flowed overwhelmingly to the top quintile of income-earners, who have seen their wages increase by over 25% over the past 25 years. In a shocking comparison, income levels have declined for low-income households since 1989, a clear sign of a widening wealth gap in the region. Those at the bottom also find themselves working harder for less money: the average income for those living above the previously described real cost of living in Santa Clara County stands around $27 per hour, whereas the average income for those living below the real cost of living comes in at a bit over $10, around the current California minimum wage.

To make matters worse, government efforts have proven relatively ineffective in remedying regional inequality. A recent study has shown that even when a family is a recipient of CalWORKS and CalFresh benefits, government-funded initiatives to provide benefits to needy families, an average family of four is still tens of thousands of dollars away from comfortably subsisting in Santa Clara County. Additionally, government benefits are not reaching populations that would benefit from them the most: a United Way study found that less than 19% of single mothers and less than 5% of immigrants statewide subscribe to these programs.

Shifts in the Regional Economy

Efforts to increase wages of low-paying jobs may alleviate financial hardship to a certain degree, but these actions fail to consider an underlying trend in Santa Clara County: low-skilled, blue collar jobs are disappearing. Wage increases in industries heavily populated by lower income earners matter little if those jobs do not exist. Historically, Santa Clara County was a manufacturing hub, famous for producing semi-conductors along with other components vital to the burgeoning technology industry. However, recent years have seen manufacturing jobs leaving the area in droves, either to other parts of the country or abroad.

Sector growth in the region, percentage change, 2000-2014.

The chart above shows that job growth in Santa Clara County has only been observed in a few sectors of the local economy. Despite this growth, total nonfarm payroll employment has decreased in the past 15 years, and the impact of this job loss may be observed across the economy. The most significant reductions of the workforce have occurred in sectors referred to as “blue-collar,” typically middle income jobs that may or may not require higher education. These types of jobs cover many of those within the goods-producing sectors, comprised here of the mining, logging, construction, and manufacturing industries.

The rapid decline of “blue collar” jobs in the region may be attributed at least in part to the explosive growth of Silicon Valley. As the region attracts more skilled workers, increases the region’s desirability, and pays workers competitive wages capable of keeping up with costs of living, those very expenses will continue to drive upwards. As a result, workers across all economic sectors have demanded higher wages, a sentiment exemplified in the recent minimum wage hikes. Unfortunately, this drives lower-paying blue-collar industries to relocate, often out of the state, so they can lower their input costs, creating a polarized society of high-wage earners in the information sector along with low-wage earners in a service sector dedicated to the needs of the technocrats.

Santa Clara County is a place of immense, but heavily-concentrated wealth. Multi-billion-dollar technology campuses dot the landscape like behemoths, yet the wealth and progress that accompanied the growth of the Silicon Valley has also left a significant proportion of its population behind. The environment is increasingly hostile to social mobility, the manufacturing sector has skipped town, and government efforts to mitigate the effects of these changes have proven relatively unsuccessful. Trends have shown that the region’s poor are increasingly confined to specific industries and geographies, and their freedoms restricted as they are subject to a degree of economic violence that shows no immediate signs of relenting. Significant shifts in local policy are needed to reverse the current social and economic trends and ameliorate the situation in an increasingly polarized Santa Clara County.

Alex Thomas is currently a sophomore at Chapman University pursuing a major in Political Science. He is originally from San Jose, California, and has worked extensively within the city and surrounding areas. He hopes to further his interest in local politics through continued study and community involvement in the upcoming years.

Photo: Coolcaesar [CC BY-SA 3.0], via Wikimedia Commons