“Shame is fear of humiliation at one’s inferior status in the estimation of others.”—Lao Tzu.

Sitting with fellow Clevelanders at a since-demolished bar, July 7th, 2010, LeBron James, local boy, uttered the words that hurt: “I am taking my talents to South Beach”. It was a shot heard around the world, but felt sharply inside the Rust Belt city’s heart.

“He had before invoked all the connotations of home, only to leave it,” wrote Cleveland sports columnist Bill Livingston the next day, in a piece entitled “By rejecting his hometown team, LeBron James earns his slot on the [Art] Modell list of shame”. Livingston upbraided LeBron for scheduling a cable event to “exploit this city's suffering”. His words were intent on shaming LeBron for leaving, yet in doing so reared Cleveland’s collective shame for having again been left.

Collective shame is an underappreciated subject. But it, like other collective emotions—think fear and pride—run our societies as noted by the great sociologist Emile Durkheim.

For decades, Cleveland has been held together by a solidarity in loss, especially the collective shame that came with it. Unlike guilt, which is about what one did, shame is an affront on the self, or what one is.

And what was blue-collar Cleveland without a wealth of blue-collar jobs? It was a city of losses—be it of income, population, and a way of life.

Walk down many Cleveland streets and you can see how this loss has played out in disinvestment. Often, the effect on the viewer is the same: status was here, but no longer. The constant reminders of loss give shame currency. Cleveland is not alone here. Cities the world over are afflicted with the hangovers of history. From the “Geography of Melancholy” in the American Reader, the author writes:

Nearly every historic city has its brand of melancholy indelibly associated with it—each variety linked to the scars the city bears. Lisbon has its saudade: a feeling of aimless loss tied to the city’s legacy of vanishing seafarers, explorers shipwrecked in search of Western horizons. Istanbul has huzun: a religiously-tinged brand of melancholy rooted in the city’s nostalgia for its glorious past.

Instead of seafarers, Cleveland had steelworkers, and others who’ve had their working-class status stripped. Yet while the loss was personal, it was the result of macro forces, leaving many feeling powerless and alone. This aloneness was tied up in the feeling of shared suffering. “The very fact that shame is an isolating experience,” notes the author of “Shame and the Social Bond”, “also means that if one can find ways of sharing and communicating it this communication can bring about particular closeness with other persons.”

There are many ways collective emotions are shared. Much of the vessels are informal. Think oral tradition and rumors. Fashion is another channel, like a city’s t-shirts. In fact perhaps nothing says implicit understanding between natives like city mottos emblazoned chest level. Cleveland’s most famous t-shirt said simply: “Cleveland—you’ve got to be tough”. It was made in 1977, in the heyday of the city’s decline. You had to be tough in the face of a post-industrial headwind. Today, iterations remain on this “the world is against us” mentality. “Defend Cleveland” and “Cleveland VS Everybody” t-shirts are worn liberally. Another favorite that tips more toward shame than to a defensiveness against judgment says: “Cleveland Low Life”—a play on “Miller High Life”.

Is all this productive? No doubt, collective shame, according to scholars, can strengthen the bonds between members of a group which, in turn, can lead to a process of self-exploration and restoration of a social identity. Or it can be chronic. Cleveland is well-known for its self-flagellation. It’s especially obvious to folks who aren’t native Clevelanders.

“I have, in fact, never lived in a place whose proud residents so consistently and gleefully disrespect their hometown as Cleveland,’ notes legendary Jeopardy champ Arthur Cho in his recent Daily Beast piece “Cleveland Comes Crawling Back to LeBron: The Masochism of Rust Belt Chic”. Cho, a Cleveland newcomer, goes on to write that though he hates to “engage in victim-blaming”, the reason “everyone dogs on Cleveland is that we ask for it”. Why? Cho concludes: “If we weren’t suffering, we wouldn’t be Cleveland anymore.”

But this Cleveland mindset does little for opening the region up to new ideas. Just as the messages become defensive, so do the policies and politics. Nativist culture reigns. Nepotism and patronage become the grease that runs the status quo. And so the communal shrouding effectively disables the possibility of possibility. Hence, the region’s struggles in its economic restructuring in the era of global connectivity.

In that sense, Cleveland’s collective shame can be a source of bad policies which ensure the collective shame. But why would a city want to do that, albeit implicitly, subconsciously?

“Economic struggle can be a cultural unifier in a community that people tacitly want to hold onto in order to preserve civic cohesion,” writes urban theorist Aaron Renn in Governing. Beyond that, those with power can lose it with community change. Continues Renn:

…[I]t isn’t hard to figure out that even in cities and states with serious problems, many people inside the system are benefiting from the status quo.

They have political power, an inside track on government contracts, a nice gig at a civic organization or nonprofit, and so on. All of these people, who are disproportionately in the power broker class of most places, potentially stand to lose if economic decline is reversed. That’s not to say they are evil, but they all have an interest to protect.

Does this mean Cleveland is doomed? Hardly. The region is experiencing a brain gain. It has incredible assets—namely, its educational, hospital, and cultural institutions—that have been dragging it along toward a point of turning the page. But more is needed. Specifically, more perspective—a perspective that the city’s inferiority complex isn’t about what others think of Cleveland, but about what Clevelanders are compelled to think about themselves.

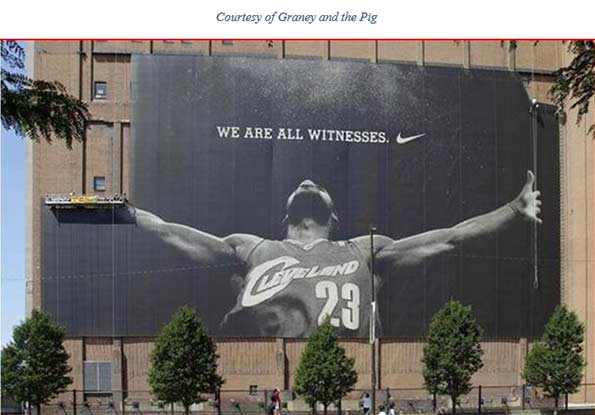

Which brings us back to LeBron. Soon after his announcement that he was leaving, The Onion wrote a satirical piece called “Despite Repeated Attempts To Tear It Down, Massive LeBron James Mural Keeps Reappearing”. In it, the iconic “We are All Witnesses” banner keeps hauntingly resurfacing. At one point in the piece, city workers removed it panel by panel, “only to find an identical mural hanging directly behind it”. The article ends, “As of press time, nobody outside the Cleveland area had seen the mural once since it was originally taken down…”

The takeaway, then: When suffering has become your identity, you have clearly suffered long enough.

Cleveland’s path to progress means letting go of that which has stubbornly remained. There’s hope that the change is coming, largely due to the presence of the new generation.

In many ways LeBron is an embodiment of the next generation of Cleveland and the Rust Belt. His return epitomizes possibility. No, I am not talking about championships here, nor the collective Prozac-effects that a parade down E. 9th St. would have on the region’s psyche. Instead it is about perspective.

The day LeBron announced his decision he was leaving Cleveland, he was in Akron. According to an ESPN piece, he knew the decision would hurt people, and that nothing would ever be the same for him. “Somehow he got through the final day of his annual basketball camp in Akron without confessing,” the authors write. “By the time [former teammate] Damon Jones drove him to the airport, where he would fly to Connecticut and reveal his infamous decision to the world, there was a lump in his throat.”

LeBron, like all sons and daughters of the Rust Belt, is a product of collective shame, and so his self-battle with leaving is no surprise. But sometimes leaving is the answer. No person should ever self-sacrifice out of a loyalty to place. And sometimes coming home is the next answer. If only because intermittent personal aspiration will often take a backseat to that evolutionary and endearingly human need to belong.

The secret sauce, here, is the perspective gained in the journey. And then bringing it back to a community that could use more than its fair share.

Richey Piiparinen is a Clevelander, writer, and Senior Research Associate heading the Center for Population Dynamics at Cleveland State University.

Lead photo courtesy of Michael Lapidakis.

Cleveland may have more than it thinks

You might want to check this out. Cleveland may be at the front end of a new American beginning:

http://www.thenation.com/article/cleveland-model