Recently I suggested that in New Zealand we are heading into the perfect housing storm. Now we have news that house prices and rentals are on the climb again, although stocks remain tight, as an annual inflation rate of 5.3% hits a 21 year high. The economists are suggesting this is good news, although it means interest rates may have to be pushed up sooner than expected.

Well the bad news is that the housing crisis might just have worsened.

Sure, its not an across-the-board crisis, but it is very real to large and important sections of our population. Lack of housing affordability remains a threat to social sustainability and economic recovery. So how are we responding to the threat -- or perhaps now the reality -- of a perfect housing storm? What provisions are we making in our urban plans?

Smaller boxes – bigger footprint

Urban planners are still more preoccupied with fitting more dwellings into smaller areas than they are with responding to people's needs for housing. It might help shift this fixation to point out that the preferred compact city solution is not only socially destructive, because it doesn't reflect need and does nothing for affordability, but it is also environmentally short-sighted.

Think about the metrics.

Take 100 people and house them at 1.5 residents per dwelling. That’s arbitrary, but it reflects a widespread expectation that most new dwellings will house smaller households in central locations.

In the interests of sustainability, let’s assume the resulting 67 dwellings are small, so that we can fit more of them onto less land. Say, 120 sq meters per dwelling. That totals 8,000 sq metres or thereabouts (more if we count the common areas in apartment buildings), 80 sq metres per person. It’s also 67 kitchens, 67 lounges, maybe 67 media centres, at least 67 bathrooms, maybe some additional lighting for common areas and even some lifts.

Now take 100 people and fit them in at 3 people per dwelling, terraces, duplexes or fully detached houses. Let’s make the dwellings bigger, say 200 sq metres. We now need only 33 dwellings, 6,600 sq metres of dwelling, or 66 sq metres per person. Less space per person, sure, but that's okay because now we need just half the kitchens, bathrooms, lounges and media centres. However we look at it, we’ve used a lot less resources and have a spare 1,400 sq metres for open space, extra gardens, courtyards, whatever. And with the capacity for extra bedrooms, we have much more flexible housing stock.

So which is the more sustainable? Surely bigger dwellings with higher occupancies. Surprised?

Can we plan for higher occupancies?

Now, we can’t engineer household size, can we? Well, actually we already do. With a housing shortfall we now require young adults to stay longer with their parents, force singles to move in with others, require couples to take on boarders, or even promote multi-family living, all boosting occupancies.

So let’s at least understand that building more, smaller dwellings, especially medium- or high-rise apartments, does not necessarily deliver sustainable urban settlement, nor does it provide the flexibility to make the higher occupancy "solutions" we force on people easy to live with.

Larger dwellings do allow for diverse living arrangements, but its more multi-generational living, more non-family households, more sharing. Like them or not, such arrangements are likely to increase, if only in response to the affordability issues we seem intent on entrenching.

So what’s happening to demand?

So why are planners trying to put more people into smaller dwellings anyway? How relevant is the expectation that average household size will be smaller in the future than it has been in the past?

Most forecasts of housing “demand” simply extrapolate diminishing occupancy across demographic projections. Its all about the coefficients, and the assumption that household structures won’t change much in the medium to long-term.

Well, it’s not that simple.

Things like an unexpected boom in the dissolution of relationships over the past three or four decades, the rapid growth in migration, and the recent stabilisation and even reversal in occupancy rates undermine the conceit that we can accurately forecast the structure, preferences, and behaviour of households 20 or 30 years hence. If that's the case, why are our prescriptions for housing increasingly rigid?

Projecting household types

To understand this let’s stay with the current ”best” projections of what households might look like in the future, and think about the implications for housing.

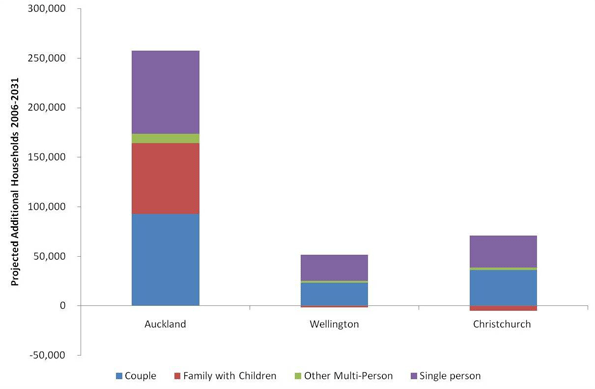

Statistics New Zealand (SNZ) medium projections to 2031 indicate that families with children will account for a minority of household growth in our main cities (see chart). The figures may even shrink in Wellington and Christchurch. According to this projection, they will make up 28% of new households in Auckland, though, so we could still need over 71,000 new dwellings for families there. It’s reasonable to expect that detached housing will still work best for them.

|

| Household Category Projections, Statistics New Zealand |

Couples will account for more growth, though, maybe 36% of new households in Auckland according to SNZ, and singles for 32%. So let's think about the preferences of the small household segment.

So what will the small household segment look like?

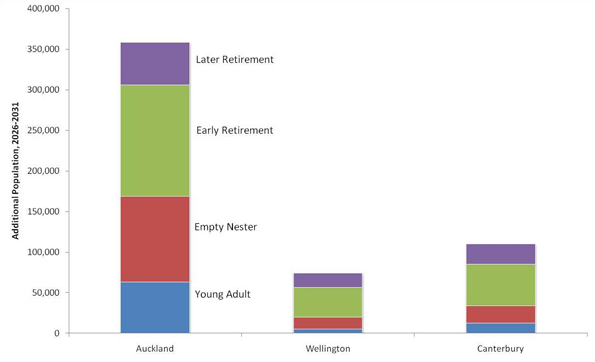

To get a feel for this, I divided the SNZ age projections into four (setting aside the main family age cohorts) : young adults (aged 20-29), empty nesters (the kids have left home, aged 50-64); early retirees (65-79), and later retirees (80+). These are the groups most small households will come from. But they have quite different housing preferences, so the nature of future demand for smaller dwellings depends on which ones grow the most.

|

| Age-Based Housing Demand Segments (based on SNZ Projections) |

So who will dominate growth?

Empty nesters and retirees will dominate the demand for new houses. And these are not usually people who want to move into small, centralised apartments, at least not as a primary residence.

Many of them have significant financial equity in their existing homes and emotional equity in their neighbourhoods. If they move into smaller dwellings, they won’t be that small! They will expect them to be well appointed and well located, probably close to where they already live.

They won't want high or even medium rise. And they are likely to seek three or four bedrooms. They will need the space to maintain active lives into their seventies and eighties, more so than past generations. They will be accommodating visiting family and friends; they will need offices, hobby areas, workshops, and storage.

Here’s a model to take seriously if we are serious about sustainability

And as the baby boomers eventually become less independent, we might expect them to head into retirement villages, already a booming – and highly sustainable – form of housing.

In fact, we should look seriously at retirement villages if we want to understand the sorts of arrangements that could dominate new housing demand over the next 30 years. Here, the market seems to have got it right.

They offer varied living arrangements – detached and semi detached housing, terraces, apartments, and even on-site nursing facilities. They offer medium density living with plenty of green space and gardens; common areas and shared facilities for recreation and leisure; plenty of on-site activity to cut down transport needs but also on-site parking to reflect the realities of modern living. They achieve density and sustainability with style. And – there must be a lesson here – they do it overwhelmingly in suburban if not city edge localities.

So let's not assume that rising house prices mean a return to business as usual. Far from it - freeing up the housing market must remain a top priority if the economy is in recovery mode. And let's start looking to the suburbs and beyond for the housing solutions that might just help it stay that way.

Phil McDermott is a Director of CityScope Consultants in Auckland, New Zealand, and Adjunct Professor of Regional and Urban Development at Auckland University of Technology. He works in urban, economic and transport development throughout New Zealand and in Australia, Asia, and the Pacific. He was formerly Head of the School of Resource and Environmental Planning at Massey University and General Manager of the Centre for Asia Pacific Aviation in Sydney. This piece originally appeared at is blog: Cities Matter.

Photo by flickr user: Adam Foster.

Good design, not numbers, is the solution

1. I've not yet come across a planning policy in NZ that limits dwelling sizes in intensification scenarios, only in the 'traditional' suburban development that you suggest is a better model. In central areas the rules are usually exactly the opposite - eg, Auckland City's old minimum (not maximum) area apartment standards. So just where do you get the idea that planners are forcing people into smaller units for central development? Developers build small central apartments as a result of market demand, not due to planners' restrictions, because there is a real demand for that product. No market demand, no small apartments, right? Unless you admit the market-led model is flawed of course....

2. I'm totally with you on the desirability of building larger homes as part of intensification, including amenities like gardens suitable for children. I've lived in homes like this in other countries - the models exist, we just don't do them well yet in New Zealand. Intensification does not automatically equate to shoeboxes, period, and any assertion that it does signifies a lack of awareness of design solutions, and lack of awareness of the consumer demand for a large house with garden in a central, established neighbourhood. As usual, relying on planning 'metrics' without reference to actual housing designs misses this issue, which is why the new Auckland Plan pays specific attention to what makes a quality housing product and how it can be delivered in central areas.

Being able to afford these for most people is of course a much more broadly influenced issue encompassing a huge range of drivers in addition to the role planning plays. Not least is the role of the product suppliers in the marketplace. If all the products we build equate to Holden Commodores and Suzuki Swifts then we will miss out on the large middle-market sector who want a Toyota Corolla or any of the moderately sized and priced variants that cater to various lifestyle / lifestages.

3. I'm not clear how you can reconcile your general argument that planning for intensification housing leads to poor results, and then observe that retirement villages can employ all of the usual intensification design strategies and be successful. The argument that these are all suburban is clearly fallacious - do you want me to run off a list of those within a short bus ride of Auckland CBD?

4. What really puzzles me is how much of this contradicts the research observations that you record from interviews with people in the work you did for CHRANZ this year (available on their website). Are you really suggesting here that the people who chose to live in intensification housing models are unhappy or suffering in some way? Your research evidence seems to contradict your opinions.

Undoubtedly there is much to improve with the quality of intensification housing. But this is really a design problem, not a planning problem, according to your own research. Not surprising that we have poor intensification results through reliance to date on crude RMA-based mechanisms, given the legislation's lack of attention to urban considerations and design considerations.

I'm not talking about high-end design...just good design of the basics of housing: space, light, privacy, orientation, amenity, character, personalisation. The stuff that is easy to achieve in large-lot suburban models (although we still see enough poor outcomes here due to lack of attention), but needs more thought and consideration when neighbours are closer. It's not impossible to achieve, it just needs design attention. It needs more than "Planning" alone.

Tim Robinson

Architect & Urban Designer, Auckland, NZ