Overall, immigration has both positive and negative effects, something rarely acknowledged by advocates on either side. An intelligent approach would try to minimize the negatives, for example by keeping out immigrants with ties to radical anti-Western groups or who lack employable skills, while looking to attract newcomers with the right skills, work ethic, and entrepreneurial gifts.

The most compelling argument for mass migration lies in demographic trends, particularly in high-income countries. Globally, total population growth in 2021 was the smallest in a half century. Sixty-one countries are expected to see population declines of at least 1 percent by 2050. The world’s population is due to peak sometime later this century. Populations are expected to halve by 2100 in more than 20 countries, including Spain, Portugal, and Japan. The decline in fertility rates is an almost universal phenomenon as countries become more economically developed. Fertility rates will remain above replacement in Sub-Saharan Africa at least in the near future, meaning that its population and its share of the global population will likely continue to grow.

Low fertility rates mean a shrinking workforce. In the U.S., workforce growth has slowed to about one-third the level of 1970 and seems destined to fall even further. This decline harms public finances by wrecking the assumptions under which old-age benefit programs were designed. It also accounts for a significant portion of the concomitant decline in average economic growth compared with earlier decades.

Innovators, Entrepreneurs — and Servants

John Maynard Keynes warned that “chaining up of the one devil [of overpopulation] may, if we are careless, only serve to loose another still fiercer and more intractable.” Historically, rising populations and the young workforce they imply drove economic growth and innovation, as was clearly the case during Europe’s early modern heyday as well as in the great economic expansion of the U.S. Similarly, East Asia in the first decades of this century benefited from an enormous “youth bulge” of younger workers at a time when overall fertility rates had begun to decline.

In countries of net immigration such as the U.S., immigrants are critical to labor-force growth. They account for roughly 18 percent of the U.S. workforce, up from 15 percent in 2006. Newcomers and their offspring are more likely to be entrepreneurial risk-takers. Latinos, for example, now account for upwards of 80 percent of all new business in the U.S., starting at a rate three times the national average. Similarly the Asian-American share of all U.S. business has more than doubled since 2000. Foreign-born workers, overwhelmingly from Asia, make up a remarkable three-quarters of all of Silicon Valley’s tech workforce.

Immigrants make up 20 percent or more of the workforce in industries such as construction, transportation, agriculture, and leisure and hospitality. The demand for labor in these fields seems likely to continue for now, although, it could be reduced through developments in artificial intelligence and robotics.

A Smarter Approach to Immigration

In the short run, at the very least, most Western and East Asian countries will need more workers to sustain growth. But this does not necessarily mean that more is always better. Countries, including the U.S., may need immigrants but only in ways congruent with the national economic interest and political stability. Control of the border, and a thought-through, properly enforced immigration policy, is a foundation for this.

Read the rest of this piece at National Review.

Joel Kotkin is the author of The Coming of Neo-Feudalism: A Warning to the Global Middle Class. He is the Roger Hobbs Presidential Fellow in Urban Futures at Chapman University and and directs the Center for Demographics and Policy there. He is Senior Research Fellow at the Civitas Institute at the University of Texas in Austin. Learn more at joelkotkin.com and follow him on Twitter @joelkotkin.

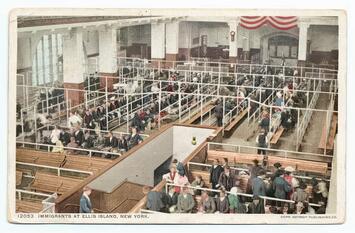

Photo: Historic immigration processing center at Ellis Island, NYC via Picryl, in Public Domain.