The world may not be turning upside down, but it’s certainly tilting. In the long shadow of the pandemic, with war on the European continent and the West and China entering a new cold war, the “new economy” of bits and bytes that was supposed to connect and shape the world has hit a rough patch. Meanwhile, the much disdained “old” economy of manufacturing, agriculture and energy is thriving.

Today, it’s not steel companies or gas plants that are experiencing mass layoffs, but firms such as Goldman Sachs, Meta, Amazon, Microsoft, Snap and Google. Last year, media companies lost $500 billion in value and tech firms have shed $4 trillion off their valuations. Industrial spaces are in high demand while downtown offices sit half-empty. The fossil fuel giants are enjoying record profits as the beneficiaries of ultra-subsidized renewable schemes, which excited investors with dreams of guaranteed profits, flounder.

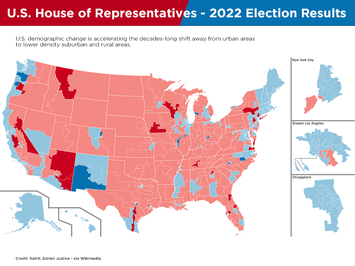

The work-from-home revolution was sparked by the pandemic but has endured long after the lockdowns ended, accelerating the decades-long shift away from urban areas. Ten years ago states dominated by big cities, such as New York and California, were riding high, or could at least pretend they were. Today virtually all the rapid growth in population and the biggest growth in new jobs is taking place in redder, lower density states like Texas, Arizona, Tennessee and Florida.

These trends amount to a fundamental geographic shift and suggest the possibility of a transformed political map. The center of American power has moved around the country time and again, starting with the frontier ascendancy over the New England elites led by Andrew Jackson two centuries ago. Lincoln, backed by the Midwest and rapidly industrializing Northeast destroyed the old south while the Roosevelts, representatives of an ascendant New York-led urban politics, shaped the first half of the last century. Later, California’s ascendancy sparked the rise of Richard Nixon, Ronald Reagan and, briefly, Jerry Brown.

Now we could be entering a new era, with people and economic power shifting to sunbelt states, some parts of the Heartland and the suburbs almost everywhere. Since 2015 smaller metros and urban areas have been gaining people at a rate far faster than the traditionally dominant big cities. Between 2010 and 2020, suburbs and exurbs accounted for about 80 percent of all US metropolitan growth.

The pandemic intensified these trends. Last year, New York, California and Illinois lost more people to outmigration than any other states. Demographer Wendell Cox notes that the largest percentage loss of residents occurred in big core cities such as New York, Chicago and San Francisco. In contrast, populations grew in sprawling areas such as Phoenix, Dallas and Orlando.

Immigrants, who previously headed to the West Coast, the Northeast and Chicago, are migrating instead to places like Dallas, Miami and even small towns in the Midwest. Los Angeles’s foreign-born population declined over the past decade.

Even before the pandemic, affluent young professionals were heading to less expensive and congested cities in search of homes they could afford. Regulations have made starting or expanding businesses in the deep blue states increasingly difficult. Last year, the biggest upsurge in new business formation took place in the Deep South, Texas and the Desert Southwest while New York and the West Coast economies lagged. According to recent analysis by Zen Business, Texas and Florida are now the country’s high-growth hotspots and are also attracting the most tech workers.

Read the rest of this piece at The Spectator.

Joel Kotkin is the author of The Coming of Neo-Feudalism: A Warning to the Global Middle Class. He is the Roger Hobbs Presidential Fellow in Urban Futures at Chapman University and Executive Director for Urban Reform Institute. Learn more at joelkotkin.com and follow him on Twitter @joelkotkin.

Photo: U.S. House 2022 Map via Wikimedia under CC 4.0 License