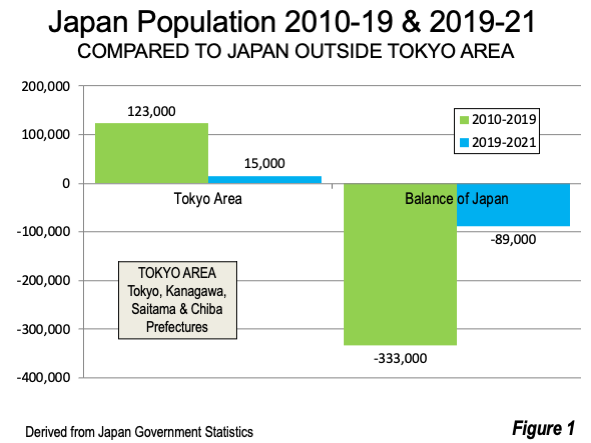

As Japan fell into population decline early in the last decade, the Tokyo area (Tokyo, Kanagawa, Saitama and Chiba prefectures), in something of a paradox, experienced population increases. Between 2010 and 2019, the Tokyo area added 123,000 new residents annually, reaching a population of nearly 37 million, remaining the world’s most populous urban area. In contrast, the rest of the nation lost 333,000 annually. During the pandemic, however, the Tokyo area suffered a huge loss in population growth, to 15,000 annually from 2019 to 2021, while the rest of Japan substantially reduced its annual loss to 89,000 (Figure 1). For background, the second level of government, analogous to states or provinces is 47 prefectures, four of which constitute one of the metropolitan definitions of Tokyo (Note).

Much of this near reversal was related to moving from the densest urbanization to areas where households are able to obtain more space for living, a pattern also evident in the United States, Canada, Australia and many other nations. The government of Tokyo prefecture “has repeatedly, and repeatedly again, called for the avoidance of the "Three Cs" (Closed spaces, Crowded places, and Close-contact settings).”

Net Internal Migration

With its low birth rate, differences in population growth between prefectures will tend to be principally driven by net internal migration (referred to herein as “internal migration”). Unlike the US, Australia, Canada, New Zealand and much of the EU, immigration is only a marginal factor in Japan.

Between 2014 and 2019 (the last pre-pandemic year), the nation lost 1.1 million residents. During the same period, net internal migration to the Tokyo metropolitan area (Tokyo, Kanagawa, Saitama and Chiba prefectures) was more than 780,000. This is an annual average of about 130,000. Net internal migration peaked in 2019, reaching 149,000. In that same year, only four of the other 43 prefectures experienced net gains, for a total 13,000 net migrants. Thus, the Tokyo area accounted for 92% of the net internal migration gains among the prefectures.

The pandemic changed things materially. Between 2019 and 2021, net internal migration dropped by more than 99% in the Tokyo area, to 1,300. The Tokyo area’s share of net internal migration gains dropped by 92%. The number of gaining prefectures rose from 8 to 22, while one of the Tokyo area prefectures fell into decline. As a result the gaining prefectures outside the Tokyo area rose from four to 19.

At the same time, outside the Tokyo area, net internal migration rose from minus 149,000 to minus 1,300.

Net Internal Migration in the Tokyo Area

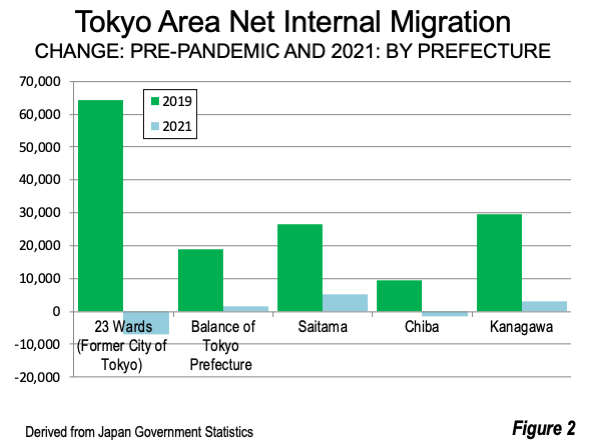

The drop in migration to the Tokyo area was concentrated in the urban core, which consists of the special wards that formerly constituted the city of Tokyo (which was merged into Tokyo prefecture in 1943). The 23 wards experienced net internal migration in 2019 that exceeded both the number and percentage achieved by any of the prefectures outside Tokyo, with a gain of 64,000. By 2021 that figure had fallen to minus 7,000.

Net internal migration also declined in the balance of Tokyo prefecture, as well as in Kanagawa, Saitama and Chiba. However, the losses from 2019 were far smaller in these areas outside the 23 ward urban core (Figure 2).

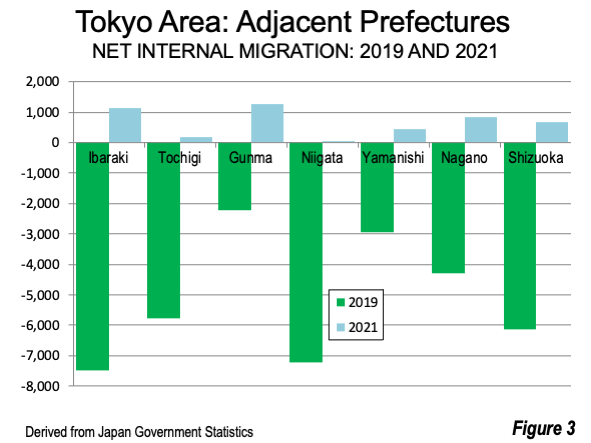

Further, decentralization is indicated by movement to the prefectures just outside the Tokyo area. These seven prefectures had all lost migrants in 2019, as a net 36,000 residents left. All these prefectures , however, gained migrants in 2021 representing a gain of 4,600, more than 3.5 times the net migration to the Tokyo area (Figure 3).

Net Internal Migration in the Osaka and Nagoya Areas

The nation’s other two most populated areas, the Osaka Area (Osaka-Kobe-Kyoto) and Nagoya experienced decentralization similar to that of the Tokyo area.

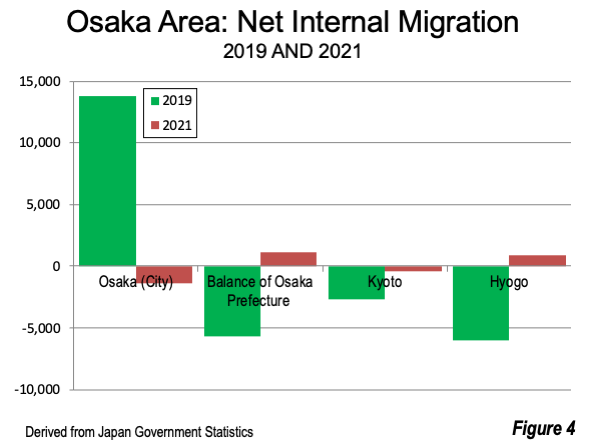

In the Osaka Area (population 18 million), the core city of Osaka gained 14,000 net domestic migrants in 2019. The balance of Osaka prefecture, as well as Kyoto, Hyogo (Kobe) and Nara prefectures all declined. By 2021, the city had a migration decline, while areas outside the city of Osaka had small gains and a small loss, all improving on their previous internal migration in 2021 (Figure 4).

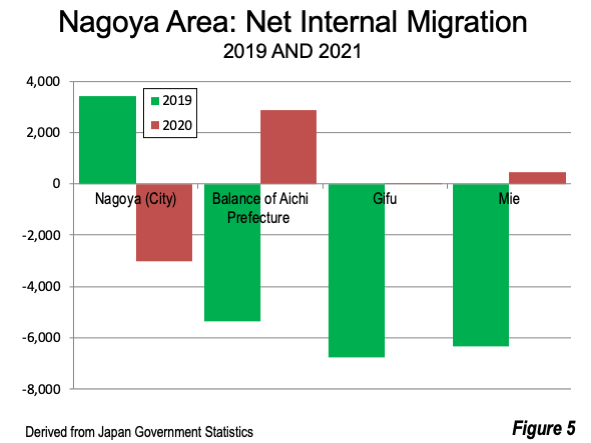

In the Nagoya area (population 11 million), the city of Nagoya had gained 3,000 migrants in 2019, but lost 3,000 in 2021. The areas outside the city all lost internal migrants in 2019 (balance of Aichi Prefecture as well as Gifu and Mie). Each of these areas outside the city of Nagoya gained between 2019 and 2021 (Figure 5).

The Future?

There is a general perception that the decentralization trend will continue. In a December 2021 article entitled “Tokyo exodus: Is the capital losing its luster among businesses,” The Japan Times cited a Cabinet Office survey of Tokyo workers indicating that 38.1% “were interested in relocating outside of Tokyo’ and that the “trend was especially pronounced among those in their 20s.” The article also reported that an international accounting firm has relocated two floors of operations from nearby Tokyo Station, arguably among the most accessible by Metro (subway) and suburban rail in the world. Yahoo Japan is vacating 40% of its space “in respond to the high percentage of employees working remotely.”

In an article entitled “Why are Tokyo residents saying sayonara to Japan’s capital,” The Guardian quotes Hiroshi Takahashi, chairman of the Hometown Return Support Centre, a nonprofit that helps people relocate from the Tokyo region to rural areas, as suggesting that a national government project “to revitalise Japan’s regions is bearing fruit.” Takahashi expects the “goodbye Tokyo” to continue after the pandemic — “In the past, work was all that mattered, but now families are thinking about their living environment, too. People’s values have changed.”

Although Tokyo has arguably the world’s best transit system, the burdens of commuting remain substantial. Tokyo has the highest transit ridership in the world, and its unparalleled rail system (also the largest Metro and suburban rail systems) and suffers from intense overcrowding during rush hour. In 2018, Soranews24 reported that 11 Metro (subway) and suburban rail (private for profit) lines operated at more than 180% of capacity during rush hour — which is calculated assuming that capacity includes not only seats, but also straps used by standees. The worst case was 199%.

According to Quartz, “In five to 10 years time, it’s possible that there won’t be crowded trains anymore,” according to a private rail executive. What’s going to drive those changes is that more companies and people will become comfortable working from home, or stagger their commutes to avoid peak hours.

Of course, Japan could resume its trend of the 2010s toward hyper-centralization, as was evident in the net migration to the Tokyo Area and the cores of the Osaka and Nagoya Areas even as the rest of the nation was losing population. Given the lower birthrates in dense urban areas, this would also accelerate the country’s continuing depopulation and rapid aging.

Yet Japan is a resilient society, and civilization. It could also embrace decentralization, as is happening in so many other areas around the world, and create a more humane, more sustainable country.

Note: The term “metropolitan” is avoided to minimize confusion. First, there are multiple metropolitan area geographic area metropolitan definitions. Further, the Tokyo prefecture government name translates into “Tokyo metropolis” and is sometimes referred to as the “Tokyo metropolitan government,” including in some of the links in this article. In fact, Tokyo prefecture is “sub-metropolitan,” with about 40% of the population in the Tokyo metropolitan area, in its least populous form (14 million of the 37 million as defined above by the Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications). There are many instances of media and even academic mischaracterization of Tokyo prefecture data as metropolitan rather than sub-metropolitan.

Wendell Cox is principal of Demographia, an international public policy firm located in the St. Louis metropolitan area. He is a founding senior fellow at the Urban Reform Institute, Houston, a Senior Fellow with the Frontier Centre for Public Policy in Winnipeg and a member of the Advisory Board of the Center for Demographics and Policy at Chapman University in Orange, California. He has served as a visiting professor at the Conservatoire National des Arts et Metiers in Paris. His principal interests are economics, poverty alleviation, demographics, urban policy and transport. He is co-author of the annual Demographia International Housing Affordability Survey and author of Demographia World Urban Areas.

Mayor Tom Bradley appointed him to three terms on the Los Angeles County Transportation Commission (1977-1985) and Speaker of the House Newt Gingrich appointed him to the Amtrak Reform Council, to complete the unexpired term of New Jersey Governor Christine Todd Whitman (1999-2002). He is author of War on the Dream: How Anti-Sprawl Policy Threatens the Quality of Life and Toward More Prosperous Cities: A Framing Essay on Urban Areas, Transport, Planning and the Dimensions of Sustainability.

Photo: Yamanote Line (central loop) at Tokyo Station (by author).

East-West

Even with decentralization, the population increases are felt in the east of the main island, while the west (Sea of Japan side) returns to nature.