Joe Biden was right to propose free Pre-K education for 3- and 4-year-olds and free community college in his initial legislative package, rather than pushing for free public university education and the cancellation of college debt. All four progressive education initiatives would serve the public good by making education more available to millions. However, policies that promote university education do little to help the working class. They also feed into the false and damaging narrative that college is the right path to upward mobility for most people.

While free public universities could be transformative in the very long term, most of the benefits of this policy would go to higher-income families. They are more likely to live in areas with high-quality K-12 schools, and their children also are more likely to have the kinds of social and cultural capital that are especially advantageous for getting into and succeeding in college.

Similarly, while forgiving all or some portion of existing student loan debt would likely benefit low- and middle-income young people, who are more likely to have higher levels of debt than their more affluent contemporaries, this too has limited benefit for the working class, because it only helps those who have gone to college. That’s a large group, but forgiving their debts does nothing for the many others who aren’t in debt because they didn’t go to college at all or for very long.

Free public Pre-K and free community college, on the other hand, disproportionately benefit working-class children and adults. Free Pre-K will not only improve the educational prospects of children, but it also saves families money. For those currently using the cheapest day care, this would save some $10,000 to $15,000 a year – a significant increase in spending power for all income classes, but transformative for low- and middle-income family budgets. What’s more, for low-income parents who currently can’t afford day care and thus can’t work full time or at all, free Pre-K would allow them to work and earn more in the paid workforce.

Likewise, free community college would disproportionately benefit low-income adults and young people who cannot go to college full time because they need to work. Community college education includes apprenticeships and other pre-training that is needed for entry into many middle-wage jobs, including in the soon-to-be-expanding building trades. Free public university would mostly benefit those young people who have more time to take the long road, while free community college is more valuable for working adults who already have work and family responsibilities.

The class-skewed benefits of these initiatives are relatively complicated, but we should also pay attention to the messages they reinforce. Prioritizing free college and student debt forgiveness plays into a toxic narrative that has deep roots in our public discourse: that college-educated people are more valuable, more worthy of public subsidy, than the so-called “poorly educated.” This narrative accepts that college graduates deserve to be paid more, but it also offers a false promise: that the primary way to increase wages and living standards – or more grandly, to restore the American Dream of upward mobility — is for more and more people to get college degrees. Both these messages are false. The first reflects a nearly impregnable professional-middle-class prejudice, but the second is an intellectual error that, if corrected, could burst a professional-class bubble.

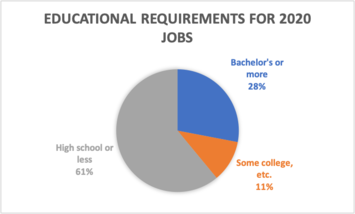

College education cannot be a path for widespread upward mobility because a large majority of jobs in our economy do not require a college education or anything like it. 61% require high school or less and another 11% require an associate’s degree, some college, or other postsecondary education – but not a bachelor’s degree.Only 28% of jobs in 2020 required a bachelor’s, a far lower percentage than the nearly 40% of workers over 25 who had that degree.

Read the rest of this piece at Working-Class Perspectives.

Jack Metzgar is a retired Professor of Humanities from Roosevelt University in Chicago, where he is a core member of the Chicago Center for Working-Class Studies. His research interests include labor politics, working-class voting patterns, working-class culture, and popular and political discourse about class. He is a former President of the Working-Class Studies Association.