“Hey!” says someone in Cincinnati every few years. “Here’s some obsolete infrastructure that should never have been built in the first place. Let’s spend a few billion dollars finishing it!”

They are referring, of course, to the infamous Cincinnati subway. If you’ve never heard of it, it is because it never operated. But if you are transit wonk, you’ve almost certainly heard of it and have probably heard some other transit wonk wax nostalgic about how wonderful it would have been if the city had ever completed it.

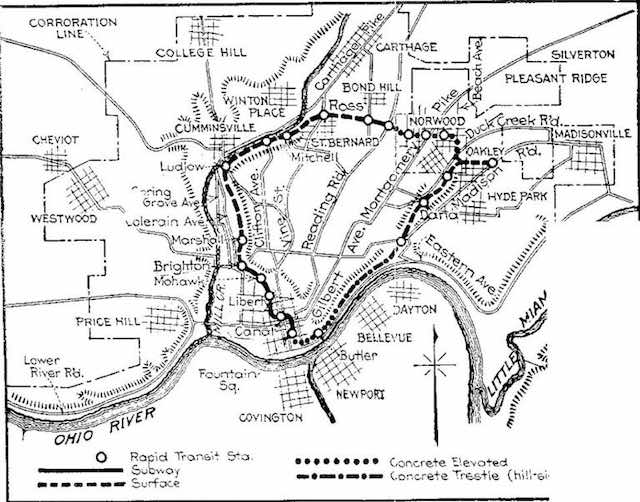

What exists of the rapid transit line (only 2 of the 16 miles would have been a subway) was built by the city in the 1920s. But when costs turned out to be double the original projections, the city was unable to finish it and gave it up as a bad job, building a highway over it instead. That road is heavily used today, but some people still believe it would have been better to have a subway.

As I noted here recently, some people naïvely believe that the New York City subway was privately built. In fact, it was built by the city using taxpayer dollars and then leased to private operators. The lease fees were supposed to repay the cost of construction but never came close. According to the 1930 census, New York City’s population was almost 15 times greater and more than three times denser than Cincinnati’s. If subways didn’t pay for themselves in the nation’s biggest, densest city, why would anyone think they could work in Cincinnati?

Map of the planned Cincinnati rapid-transit line, only two miles of which would have been underground.

The reality is that rapid transit was only rapid compared with horse-drawn wagons, but could never compete with cars in a middle-sized city such as Cincinnati. The proposed line would have circled the city but failed to reach most of its residents.

Yet otherwise sensible people say things like, the subway could be the “future for mass transit here in the city. . . . We could run light-rail vehicles in it.” Aside from the fact that the whole point of rapid transit is that it can be faster than light rail, the average Cincinnati bus (operated by the Southwest Ohio Regional Transit Authority) carried just 7.6 people in 2019. Other than to spend money, what would be the point of running nearly-empty rail cars instead of empty buses?

In 2019, less than 5.4 percent of workers living in the city of Cincinnati and less than 2.0 percent of those living in the Cincinnati urban area took transit to work. Less than 7 percent of workings living in Cincinnati live in households without automobiles and most of them don’t take transit to work. Cincinnati seems to work just fine without making more people dependent on an obsolete form of transportation.

Cincinnati’s streetcar, which was supposed to revitalize areas near downtown, trundled along in 2019 carrying fewer than 1,200 riders per weekday and performed such a non-vital service that the city shut it down during the pandemic. People should have learned from this boondoggle that transit dreams are more likely to become nightmares.

This piece first appeared at The Antiplanner.

Randal O’Toole, the Antiplanner, is a policy analyst with nearly 50 years of experience reviewing transportation and land-use plans and the author of The Best-Laid Plans: How Government Planning Harms Your Quality of Life, Your Pocketbook, and Your Future.

Photo: Jonathan Warren, via Wikimedia under CC 3.0 License.