“Almost all theories of the city are largely qualitative, developed primarily from focused studies on specific cities or groups of cities supplemented by narratives, anecdotes, and intuition.” Geoffrey West, Scale, 2017

This recent quote recalls Jane Jacobs’s seminal book, The Death and Life of Great American Cities (1961), in which she mused: “why have people professionally concerned with cities not identified the kind of problem they had?” as their colleagues in the life sciences did. She intuited that city problems “are all problems which involve dealing simultaneously with a sizeable number of factors which are interrelated into an organic whole.” Put simply, Jacobs ask the question, why is there no science of cities yet?

Presaging the birth of a science of cities, Jacobs later, intriguingly offered that, if she were to be remembered, it should be for “[…] the most important thing I've contributed [which is] my discussion of what makes economic expansion happen.” Could this be the key to finding the elusive “organic whole”? It now seems almost certain.

A Focus Shift

Two things happen when embracing Jacobs’s centrality of economic growth in describing a city.

First, a switch in perspective away from the habitual, close-up, bricks-and-mortar perception toward a vista in which a city entails much more than its built setting (e.g., streets and buildings). From this more expansive viewpoint, all of city’s physical elements are but an incidental stage, a backdrop, where city life unfolds. It unfolds by myriad purposeful activities of its people. (“Cities are fantastically dynamic places […], which offer a fertile ground for the plans of thousands of people,” wrote Jacobs.)

Though transient, mostly unnoticeable, and wholly unscripted these events and activities are of existential importance. When they subside, so does the city; its stage then a museum curiosity.

Figure 1. The Stage: The central square in Marrakech. An expansive sun-scorched emptiness during the day, the square blossoms with innumerable transactions in the evening, the “city buzz” on dazzling display. (photo by author)

Second, a realization that the activities of citizens are invariably transactional and interpersonal, irrespective of their nature or location. For interactions to happen, however, connections and contacts must exist or be created; that’s to say networks, both physical and social (formal or casual). The more connections, the greater the activity. From transactions to connections to networks, the city emerges from its physicality as a “neural” web, brimming with constant, random firings, akin to a sentient organism rather than an inert object in space. (“We ought [...] to make this living collection of interdependent uses, this freedom, this life, more understandable for what it is...” Jacobs, 1961)

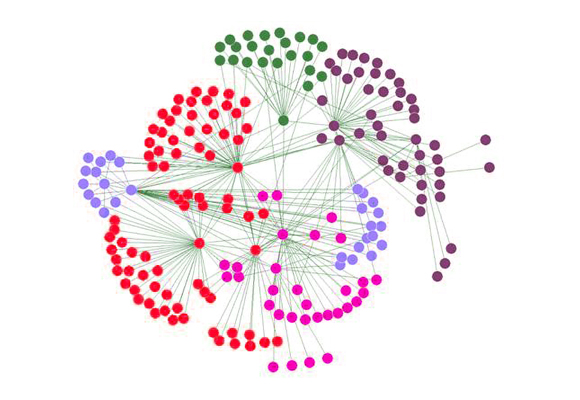

Figure. 2. Social Networks: the lens through which the city’s organic nature is revealed, the foundation on which a city is built, and the venue through which it can be studied. (Social network diagram, meso-level, Wikipedia)

To the extent this “neural” activity transcends the physical individuality of each city, it engulfs all specimens in the quest for a general city theory. Here is then a promising, dynamic, subject for study—the organic behavior of networks, revealed.

Dancing on a City Street – Intermezzo

The first three chapters of Jacobs’s book focus on streets and sidewalks; curiously, not those of small-town Scranton she grew up in (the nostalgic, postcard type), but of New York—the great metropolis to where she migrated (as did millions). Her personal journey is typical of a universal trend. Why this extensive focus on streets? Most likely because of the unavoidable sensory overload of innumerable in-person interactions taking place in plain sight. And in-person, planned, or spontaneous they had to be in the 50s; laptops and cellphones were in the future.

These interactions are The City Life on display, impossible to overlook, a natural focus of her observations. Yet, sensorially overwhelming as it may be, this sidewalk ballet is only a fraction of the sum of transactions, connections, and networks that constitute the life of the city. For every sidewalk café waiter on stage, for example, there is a chain of numerous invisible enabling actors. Ditto for every schoolchild that walks to school or a street corner peddler. Dancers on the street are just the visible portion of a large invisible troop of which most dancers remain unseen. These must be revealed and counted in a complete theory of the city. Such a theory must encompass change too. Walkers now, perhaps even the majority of walkers, and even in company, interact with an invisible something via their cellphone, entirely oblivious to their surroundings—life, for them, is elsewhere, not on the street where they walk. The choreography of the city street has changed because the “city” invented a new interaction mode; the street ballet mutated.

Yet, despite these absentees, the sum-total of city life, when measured in daily transactions, has increased. This ballet is inextricably tied to culture; transitory and variegated; the glittering surface of a deep river.

The Fortunes and Fate of Cities

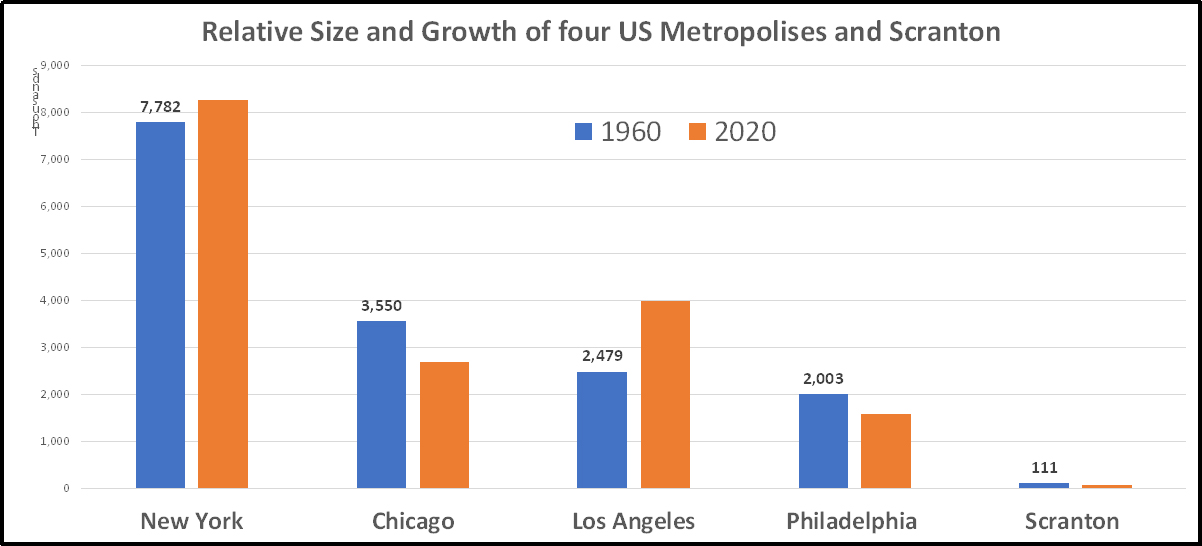

By 1961 (the year of Death and Life's publication), New York City had accumulated nearly 8 million people, twice the number of the second largest U.S. city, Chicago, and larger than 37 of 50 States.

Figure. 3. Two metropolises (New York and Los Angeles) grew in this period, two (Chicago and Philadelphia) lost population, and one (Scranton) almost emptied. (Chart by author)

Scranton, by contrast, registering just over 111,000 people, had lost 22% of its peak (1930) population and continued the slide to half by 2010. (New York City added about nine Scrantons in the same period.) Two cities, two diverging trajectories. What explains this divergence? And how can New York’s stunning growth be understood? Jacobs glimpsed at the answer.

Figure.4. Railroad yards in Scranton, c. 1895. (Wikimedia) The making and unmaking of Scranton: coal, iron, and steel. Resources and their trade shaped a city’s fate, once the “electric city.”

Sixty years since, after painstaking research, we gained a clear, scientific perspective on the Life of cities; their growth curve and what shapes it. We also now better understand the Death of cities, about which Jacobs also wrote. Her focus, however, was on the waning vitality and diversity, the wilting of community vibrance and its economic activity, most of which, she accused, resulted from unwise, ill-informed interventions by overconfident planners and regulators—Death by intervention and by squashing organic growth.

Real death rarely, if ever happens to cities despite most dramatic and catastrophic events that occasionally befall them. Miletus was sacked once (494 BC), Rome twice (410 AD and 1527 AD), London went up in smoke almost entirely (1666), Dresden’s center flattened (1945), and Hiroshima and Nagasaki were virtually obliterated (1945). Yet, all these cities revived and flourished. A city theory now explains that cities never really die because they reinvent themselves even when their physical settings are gone. They are complex, adaptive organisms—chameleon-like. Cities are not their streets and buildings.

The Primordial Journey and Economic Expansion

Wherein lies this regenerative capacity? The generic, and inadequate, “city” label and its reflexive evocation of streets and structures explains little, measures less and, by itself, stirs no desire to relocate—a plenty of indistinguishable choices. Yet certain cities attract scores of migrants and thus grow to become metropolises; others don’t grow so completely, or worse, lose residents. Among those that attract people, what exactly is their pull?

Most often a city’s “lore” creates the lure: a tale with scant facts, partly true and partly imagined but enticing and powerful. Unveiling, describing, and quantifying this magnetic force would be central to a city science that Jacobs sought. She herself succumbed to this undertow.

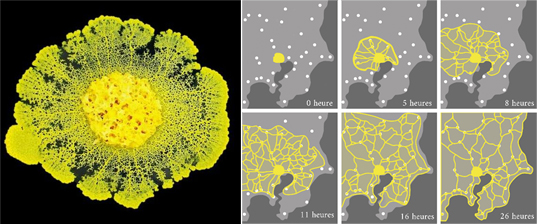

Figure 5. Slime Mold (Physarum polycephalum) finds its food and creates “supply channels” to feed its constituent parts. (Wikipedia)

Succumbing to the pull should not be surprising. From the first unicellular organisms (1.5 BYA) to the most advanced multicellular ones, the genetic survival guide reads: “follow the food.” With or without a brain, and with or without specialized locomotion mechanisms, organisms sustained themselves by moving, migrating to a food source. And therein lies the growth vector.

People are no exception: when “job” becomes a virtual synonym for “food” (or its refinement, “a better life”), they move. From journeymen to door-to-door merchants to industrial workers to expert planning consultants to retirees: a whole gamut of individuals marches on to procure “jobs/food” or, in personal terms, “a better future.” The pull is formidable, unyielding, irrevocable. When that future was distinctly fading in Scranton around 1935, its people fled. So did Jacobs.

Figure 6. What Jacobs saw: Organic growth: density, diversity, vibrancy and a mix of uses: the prime ingredients of the “good city” that together create its buzz and throb. (photo by author)

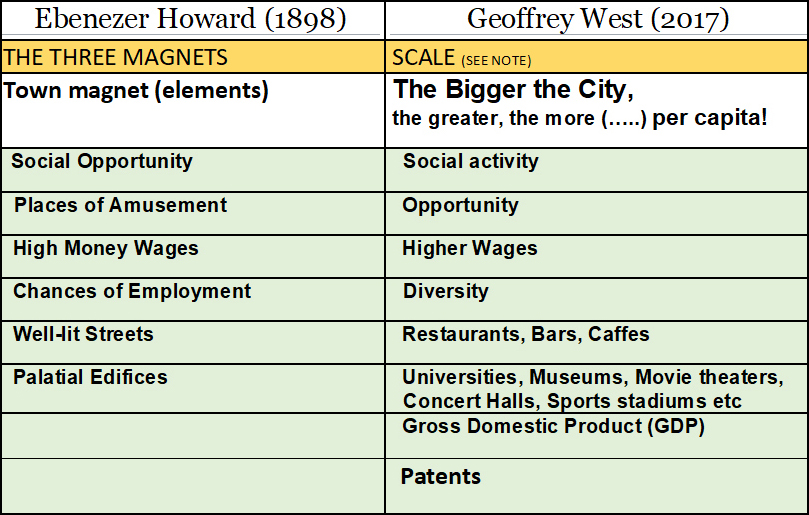

Why was New York City in 1960 such an irresistible magnet? It had diversity and vibrancy in addition to density, three interdependent attributes. Jacobs observed, and drew planners’ attention to the quintessential nature of these attributes. Mixed in with these indispensable ingredients was also a major but concealed attractor—job opportunities—of which she herself was a repeat beneficiary.

Far reaching research (furthering her initial guess), borrows principles from biology and physics, confirms that job opportunities and all three key characteristics are outcomes of economic growth and increase along with it. And, importantly, economic growth is both cause and effect of a settlement’s population size in a self-reinforcing, organic spiral. The scale of the city induces proportional pull and in turn increases opportunity, diversity, and buzz (“magic”).

Figure 7. The "call of the city." Two assessments of what draws migrants to cities. The century-old is purely observational while the recent is analytical, based on large data sets. Per capita is a critical, new measurement.

It turns out none of these attributes that so impressed Jacobs are unique to New York. They are as inevitably present in all of world’s 28 megacities as they are clearly absent in Scranton. In other words, the city “magic” springs from its population size—it is an epiphenomenon, an outcome of scale. Other, unpleasant outcomes are just as inevitable, but the subject of a future discussion.

This simple, powerful rule, along with the table list (Fig.7), allows predictions to be made, as any valid theory ought to make possible:

- There will be more megacities. This prognostication is already trending in literature. By 2030, six megacities will be added to the current number.

- Retroactively and speculatively (while not downplaying the multiplicity of factors at play) we could predict the birth of the industrial revolution in England, centered in London, based on these European 1800s stats:

- From 1820 on, England was the most urbanized European nation.

- In 1850, London was nearly twice the size of Paris, next-in-rank city.

- London had more universities that any other European city.

- China and Pacific nations will overtake the west in scientific progress. They are now experiencing staggering urbanization rates, and have the most megacities; a key to their future dominance.

Jacobs regretted the absence of true science of cities and bemoaned the practice of “pseudoscience,” berating the planning, engineering, and zoning practices of her day. What this new science implies for city planning should become a topic for further vigorous discussion. At least one thing is clear so far: We cannot cling to the “city” as an art installation in the landscape and praise or bemoan it “shape."

Note: This article owes its inspiration and most of its ideas to Geoffrey West’s book Scale (2017) and lecture as well as to Adrian Bejan’s book Design in Nature (2013)

Note 2: This article first appeared on Planetizen.

Fanis Grammenos is the director of Urban Pattern Associates in Ottawa, Ontario and the author of Remaking the City Grid: A Model for Urban and Suburban Development (i.e., the Fused Grid). Reach him by email with questions or comments.

Lead image: The archetypal, and misleading, image of the “City on a Hill.” Siena: The Wall Street of Tuscany during the Renaissance, enriching itself by being the largest regional bank. Now a UNESCO site (a living museum for tourists). Photo by author.