In a preceding article, I argued that a "city-as-an-artifact" approach to planning misses the organic nature of cities, and, when used in action, this approach could result in disappointing, if well-intended, outcomes. Similarly, biomorphic models for cities fail to construct a unified, actionable theory of planning.

The previous article pointed to the universal constancy of trip-to-work time as a clear example of a city’s self-organizing, adaptive nature, which produces robust outcomes without top-down intervention—a key identifier of an "organic whole." We also alluded to the possibility of more examples of a city’s self-organizing, adoptive nature. This article will examine a second example—the robustness of a city’s road network composition.

Self-Organizing Systems

Referring to the World Wide Web, University of Texas professor N. Salingaros writes: “None of this structure has been imposed -- it has all grown incrementally. Here we have an excellent example of self-organization, the process by which forces manage to act in balance to grow a complex system into a stable working structure.”

Similarly, while individual roads are normally built to a plan, their collective assembly tends to grow piecemeal, often in unpredictable ways, and partly because of their time scale, often many decades long. The outcome of all these separate influences resembles a patchwork rather that a neatly woven fabric. Each new addition to the system not only becomes context for the subsequent one, but is also conditioned by factors that emerge in the long interim—new modes of transportation, for example (i.e., a process analogous to morphogenesis). Moreover, once built, road systems may undergo changes that alter their composition either through gradual transformation or drastic intervention, as in the case of 19th century Paris with the works of Baron Haussmann.

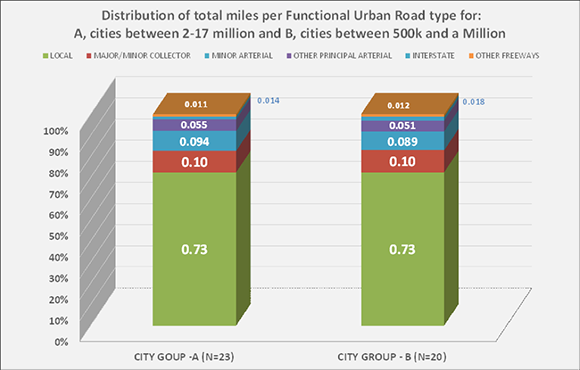

Fig. 1: Distribution of road miles by functional road type of two groups of US MSAs. These groups vary greatly in area, total road miles and population. (Source: Office of Highway Policy Information)

Given the sporadic, disjointed manner in which road networks are built, grow, and mutate, it might be expected that the outcome would be disorganized, even chaotic, as cities themselves frequently appear to be. Could there be hidden order in the apparent messiness?

What Data Show

Figure 1 answers the question of a robust working order. Though the network size of one group is a multiple of the other (341,861 vs 122,852 miles), the ratios of their parts are virtually identical (as shown by their percentages). These two groups contain cities that vary in age and geographic settings as well as to their populations, area, and densities. In spite of these differences, it seems that their road network systems maintain an invariable composition.

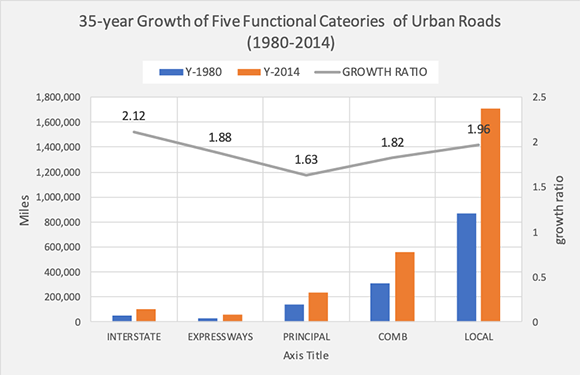

Fig. 2: Growth of Functional Road Categories in a 35-year period – nearly double. (Source: Office of Highway Policy Information. Chart by author.)

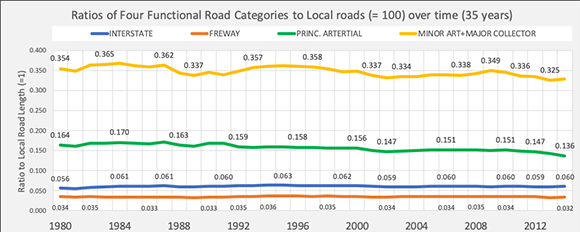

This invariable composition is true also in spite of substantial growth; in the 35 years between 1980 and 2014. (Fig. 2) they have almost doubled. It might be expected that growth might have introduced fluctuations in the network structure. As figure 3 shows, however, throughout this entire period the ratios between the constituent components of the networks have remained remarkably stable.

Fig. 3: Ratios between the six road network components, with local road miles set as a base=100 (not shown). (Source: Office of Highway Policy Information. Chart by author.)

Change and Stability

Existing city road networks regularly experience transformations—often minor, but also, infrequently, major. Examples of minor changes include the re-designation of residential roads into collectors or arterials, usually followed by selectively limiting access to the road by means of closures of intersecting streets or forced turns. Such changes sometimes necessitate widening of the pavement and adding a lane. Strategic local streets occasionally become de facto collectors or arterials by being designated for one-way traffic or by providing ramp access to a highway. Another common example of street transformation is pedestrianization, which removes a street from the vehicular network. Many more incremental changes occur over time—too many to mention individually. It is unknown whether such changes significantly affect the calculus of a system’s components given their incidental nature and their likely limited cumulative length.

Examples of major transformations at key historical points, as a result of exponential city growth, political upheavals, wars, or new transport means are limited but non-trivial. The sack of Miletus, a military event in 494 BC, gave birth to the Hippodamian grid. More recently, in the 19th century, a drastic transformation occurred in Paris, one that achieved iconic status and has been studied extensively ever since.

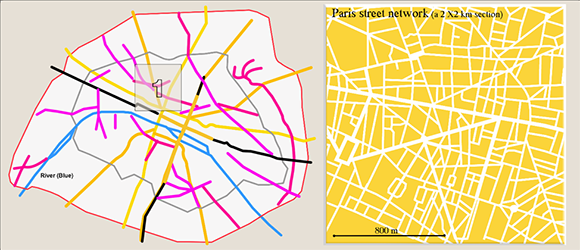

Fig. 4. Left: Hausmann’s staged (1854 -1870) circulation surgery, located within a 10 km diameter. Right: The shaded square–enlarged–showing the current grain of street structure that covers the gamut from narrow, crooked, short streets to wide, very long straight avenues (i.e., arterials); a patchwork maze of block sizes, shapes, and orientations. Graphics recreated from Paris Reborn and maps.

Change and Stability

The 19th century Paris, France’s main industrial and commercial center , experienced frequent revolts, rebellions, and uprisings, as well as consequent changes in government.. During the 20 years of Haussmann’s tenure as a prefect (Fig 4), Paris doubled in population, from nearly a million in 1850 to two million in 1870. This growth brought enormous pressures for change and adaptation on many fronts: social, political, institutional, economic, and, inevitably, infrastructural. Salingaros writes: “As it grows, a city requires larger and larger roads. A network is always driven to adjust its communication infrastructure towards and inverse power HIERARCHY. This is the reason why the mediaeval city -- with short-range pedestrian connections -- could not survive unchanged.” In this 1860s case, the infrastructure is streets, as existed in a century when the foot and the hoof were the predominant modes of transportation.

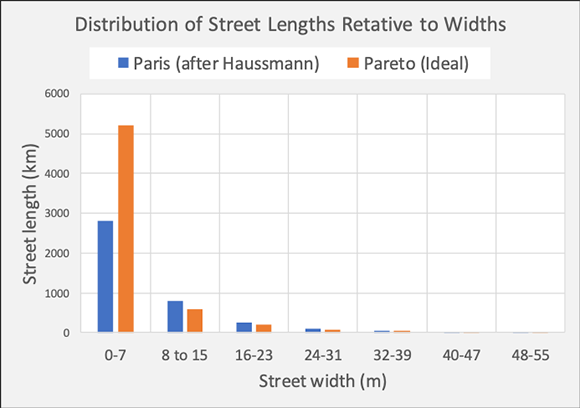

The modified Parisian network and its new organic hierarchy are shown through a chart of total street length by street width range. (Fig. 5)

Fig. 5. This graph shows the distribution according to width including the sidewalk. “The corresponding Pareto distribution is based on a fractal dimension of 1. 68, a high value that stresses a high street hierarchy.” The deviation from an ideal distribution is said to be low confirming its proximity to an optimum. (Source: Urban Morphology Laboratory. Graph reconstructed as an approximation by this author from City Forms by Serge Salat and maps.

Of the many diverse, well documented motives for the extensive transformation of Paris’ network, the restructuring of its network composition was not one of them; it was a coincidental, collateral outcome. Many old European capitals seem to have flourished without an expansive, Haussmanian surgery, instead undergoing slow, evolutionary adaptations.

The Road Ahead

This piece revealed the constancy of the distribution of road types primarily among U.S. cities over a lengthy period. This distribution inevitably reflects the multiple motorized modes that emerged in, and characterize, the 20th century, that were entirely absent in the 19th century. One might ask whether this distribution is the “correct” one for the current transportation needs. The answer can only be speculative: Not necessarily, but neither, arguably, very unlikely. If this distribution is seen as a product of organic evolution it must, in principle, serve its purpose satisfactorily or it would have been coerced into a different distribution. For now, we can only consider it as a robust outcome of a complex system. Assuming that it may somehow be found not ideal, would a Haussmann-type intervention be a proper response or the slow, bottom-up “organic” reconstitution? That's an open planning question.

This short excursion into the composition of current urban road networks confirms the possibility that road networks are one of the robust, invariant outcomes of a self-organizing system—the city - which are complex, “organic wholes,” and can be studied as such. It also raises once more the question of the precise role of planning in the evolution of cities.

Fanis Grammenos is the director of Urban Pattern Associates in Ottawa, Ontario and the author of Remaking the City Grid: A Model for Urban and Suburban Development (i.e. the Fused Grid). Reach him by email with questions or comments.

This article first appeared on Planetizen, reproduced here with thanks