By a majority of votes and voluminous citations, Jacobs tops the list of the 20th century's most influential urban thinkers. Had this been a transient fascination, as with literary works, it would be a major achievement in itself. In this case, it's far greater: an entire profession mesmerised in thought and action.

For any theorist, such total assimilation would be a triumph, complete vindication; fruits of one's ideas sprouting continuously in print and on the ground—a rare achievement. Yet, Jacobs saw the tangible outcomes of her vision as a betrayal: "They [New Urbanists] only create what they say they hate" she is quoted to have said. Such stern, unqualified rebuke of dedicated followers gives us pause for introspection. Was the rebuke justified? Do they?It matters to understand whether purposeful applications clash with theory or whether theory clashes with the realm of development. This article explores this ambivalence.

Fig. 1. Four buildings enclose a "main street" and are flanked by large parking lots on three sides at Bois-Frank, a New Urbanist development in Montreal. An unmistakable backdrop of 19th century gentry towns.

PLANNERS, PLANNING, AND NEW URBANISM

Jacobs was forthright about her disrespect for mid-20th century planning professionals, accusing them of practicing the "pseudoscience of bloodletting doctors." In a sustained, stinging criticism she exposed a pernicious and patronizing obsession with visual order and a lack of understanding of "the intricate and complex order" of the city as a living organism. Such admonitions and repudiations, along with the supporting revelatory insights, sunk in thoroughly. So complete was this hostile takeover of the professions culture that even the accreditation "Planner" was tarnished and displaced by "Urbanist."

Humbled and eager to lead, urbanists crafted a new credo, articulated it precisely and promulgated it vigorously. Henceforth, no academic article, city report or policy document would omit a reference to Jacobs's ideas. Rational defenses were built against "blinkered" professionals that she denigrated: traffic engineers, modernists, policy makers, architects, and public officials. There would be no slack given to "dis-urban" practices of yesterday. The new ideas would be promptly structured into simple commandments; the structure's cornerstones were already plainly laid out in Jacob's book: Density, (chapter - 11), Diversity (chapters 7 and 8), Design (Chapter 9), and Destination (also 7,8). All past and new developments must henceforth pass these (4-D) filters.

First to fail the 4-D test was the totality of a half-century of metro expansion; it met none of the criteria. Promptly, the body of the modern metropolis was surgically severed in two: the "city" and the "anti-city"—the "nowhere" of the suburbs—with a tinge of indignation. A persistent application of the vision's principles, was argued, would usher an urban renaissance—a New Urbanism—with unquestionably beneficial outcomes. Does the report card so far show progress?

WORK, PRINCIPLES, AND DISPARITIES

The first marks evaluate the overall effort to confront and push back on the "anti-city" tide, intellectually and on the ground. When judged by the sheer number of works in all media, the intellectual effort has been, indisputably, effective. For example, a previously idolized word—suburb—gathered a glut of pejorative connotations and joined by a disreputable companion: "sprawl." Among city mentors and casual observers, the anti-city enemy now had a face and a name, a decisive pro-city cultural win. What of the corresponding movement on the ground?

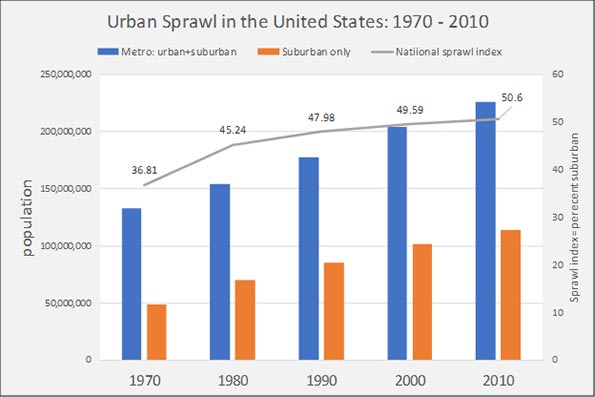

Fig 2. Outcomes of a 50-year effort against anti-city forces: a more urbanized nation and more suburbanized metros. Chart Based on: Urban Sprawl in the United States: 1970-2010 by Russell Lopez

Fig 2 shows a sizeable retreat: not only the anti-city offensive has not been held back, it shows exceptional resilience and continues to expand. Since the 1940s (at 13.4%), the share of suburban population almost quadrupled. The anti-city camp in the United States is now entrenched and holding over 50% (114 million) of metro populations hostage, living at densities between 0.3 to 5.5 pp/per acre, far below a minimum "city" density (about 20+ pp/acre) and lacking any "urban" attributes.

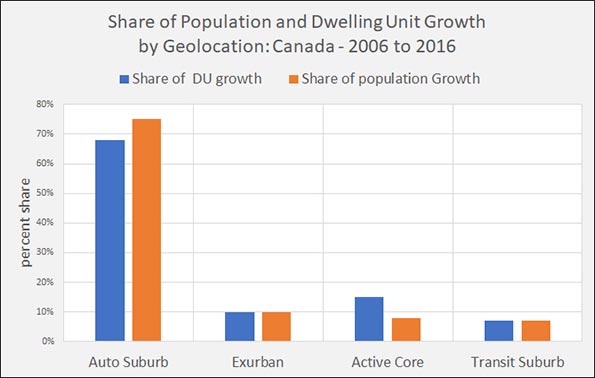

Fig. 3. Canadian Metropolitan Neighbourhood Dwelling Unit Distribution for 2006 and 2016 (Chart based on David Gordon : Still Suburban? Growth in Canadian Suburbs, 2006-2016 )

Similar trends are evident in Fig.3: Suburban development absorbed 68% of dwellings and 75% population growth in Canadian CMA's over a ten-year stretch between 2006 and 2016. Exurban development absorbed an additional 7% of metro growth—the lion's share of metro growth. That trend is also traceable to preceding decades. Before 2006, there were about 42 New Urbanist communities being built or completed in Canada. These amounted to a maximum of 110,000 dwelling units, spanning a period of about ten years prior to 2006. In the same period at least 1.5 million dwellings were added to the Canadian stock. This 1/10 ratio of NU developments attests to the degree of market penetration of the new model. Both trends show that, for all the intellectual prowess of the pro-city efforts, losses rather than gains were the outcome on the ground.

This large disparity between an absolute conquest in the cultural domain and retreat on the ground seems puzzling. At least one explanation sounds plausible: "Private investment shapes cities, but social ideas (and laws) shape private investment. First comes the image of what we want, then the machinery is adapted to turn out that image. The financial machinery has been adjusted to create anti-city images because, and only because, we as a society thought this would be good for u.," (p 313, my emphasis) Put simply, the anti-city enemy is us. This outcome could be seen as "…a manifestation of the freedom of countless numbers of people to make and carry out countless plans – [and] is in many ways a great wonder." (p 391)

Fig 4. Alluring, idyllic images of town and country

With an expectation that a new, alluring image might dislodge the entrenched one and propel the pro-city movement forward, a frame for such an image emerged in "The Second Coming of the Small American Town" (1992), molded persuasively on the 19th century "town" and "village." "The future, does not have to be imagined so much as remembered" was argued. It had a harmonious appearance and its original subject checked out all four filters of "city-ness." A "back to the future" meme summed it all up.

Following suit, of the 400 recorded new urbanist developments in the United States, spanning about 35 years, one in five has a Village (57), Town (25) or Commons (8) tag alluding to their intended form and character: A "complete," vibrant community with "lively" streets, where living, work, and play happen on location. Did such outcomes materialize?

DISCONNECT AND DISENCHANTMENT

Substantial evidence from the ground shows that they did not. In most cases, at least two of the four filters could not be fully satisfied in green-field developments: Density and Diversity, the key attributes of a good city according to Jacobs. (We will visit the rest elsewhere.)

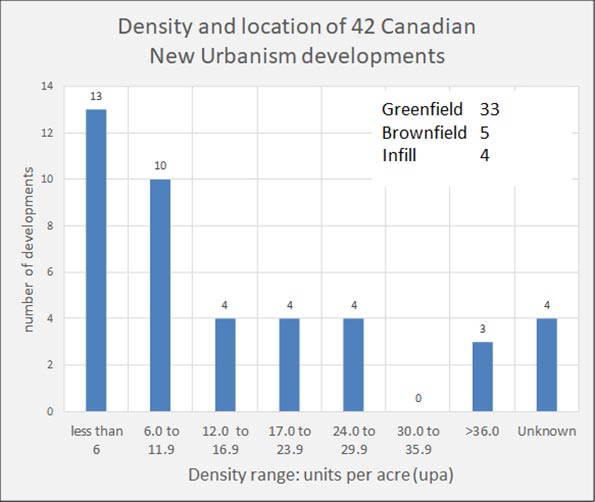

Fig 5. Known Canadian NU developments as of 2006 (42) and their geographic location. ( New urbanism developments in Canada: a survey Jill L. Grant; Stephanie Bohdanow)

Figure 6 shows that over 75% of the 42 Canadian NU developments were on greenfield sites and over half did not attain high enough density for regular bus service or for local shopping (and well below a hypothesized "liveliness" threshold). As for diversity, a representative sample of eight communities, (four of each type) selected for comparative analyses, shows that in all cases no rental units are provided; average income households ($45,800 CDN) are barely represented (at 5.7%); and the top three tiers of income constitute the decisive majority (61.3%). Evidently, both development types serve affluent, ownership households, creating exclusive new communities by means of price, just as previous ones did. To that point, average housing prices are 20% higher in the CSD communities, reflecting the higher ratio of single-family detached units (CDS-75% Vs NUD-39%).

Various explanations for these unwelcome outcomes have been attempted. But convincing arguments made earlier imply that the hoped-for outcomes are, in fact, impossible. First on account of economic factors: "[….]. But knowing what to want, although it is a first step, is far from enough. The next step is to examine some of the workings of cities at another level: the economic workings that produce those 'lively' streets and districts for city users." (p 140)

Second, the economy again: "The solution […to avoid the ravages of apathetic and helpless neighborhoods] cannot lie in vain attempts to plan new, self-sufficient towns or little cities throughout metropolitan regions" (p 219), and further on: "We cannot have it both ways: our twentieth century metropolitan economy combined with nineteenth-century isolated town or little-city life." (pp 219)

And thirdly, the limits of suburban arrangements in producing city life: "These [suburban 6 du/a or 10-20 du/a] arrangements, although they are apt to be dull, can be viable and safe if they are secluded from city life; [………] They will not generate city liveliness or public life – their populations are too thin – nor will they help maintain city sidewalk safety. But there may be no need for them to do so." (p 209)

CONCLUSION

New Urbanism practitioners embraced Jacobs's pro-city, anti-suburb sentiments with zeal and a determination to eradicate the "scourge." At the end of a 30-year, intensive effort, what emerged at the city periphery—where most of the growth occurs—were well-styled, orderly suburbs, joining an overabundance of conventional ones as the metropolis expanded. Jacobs was right to criticize the obvious disparity between intent and outcome.

But Jacobs was wrong by misdirecting the rebuke. As Jacobs was deeply aware: "Cities happen to be problems in organized complexity, like the life sciences" (p 433) consisting of many variables that are "interrelated into an organic whole." This organic whole, continually evolving, is our present metropolis that indissolubly includes its suburbs, the newest arrivals in its long history. "To see complex systems of functional order as order, and not as chaos, takes understanding" (p 376). Planners are just one of many agents of change—an undeserving target—in a complex system.

A clear lesson emerges from the disparity between intentions and outcomes: the future has to be imagined not remembered. A gathering storm of city-shaping forces now converge over the metropolitan arena, post Jacobs, encompassing the Internet, Google, Amazon, Facebook, Telework, Uber, AVs, Quadcopters, Scooters, etc. No memory of these forces exists—only prospects.

This piece first appeared at Planetizen.

Fanis Grammenos is the director Urban Pattern Associates in Ottawa, Ontario and the author of Remaking the City Grid: A Model for Urban and Suburban Development. Reach him by email with questions or comments.

Note: All quote page references are from Jane Jacobs, The Death and Life of Great American Cities (1961)