(In the mid-1980's the Chicago White Sox were struggling on many levels -- to win on the field, to excite a fan base, and to upgrade their old home ballpark. That spurred them to push for a stadium deal either in the Chicago area or elsewhere. The Sox nearly moved to suburban Addison until the promise of a new stadium was narrowly defeated in a referendum, and nearly moved to Tampa Bay until the Illinois State Assembly intervened. That deal brought us the Guaranteed Rate Field the Sox have today, which opened in 1991. But another lofty proposal was available that could've transformed not only the Sox but the entire South Side -- and indeed, the entire city, potentially setting it on a completely different trajectory. Let's imagine what could have been. -Pete)

It's the start of the 2019 MLB season, and the Chicago White Sox are celebrating their 25th anniversary in Armour Field, the retro baseball palace that completely reinvigorated the team, the community and the sport. Since moving into the ballpark in 1994, the Sox recaptured the hearts of Chicagoans and ushered in the transformation of much of the South Side. It's worth noting how the Sox went from second-tier status in the Second City, behind the despised Cubs, to one of the most popular franchises today.

Back in the '80s the Sox were facing an uphill battle, on the field and in the hearts of Chicagoans. The success of the Cubs, who nearly went to the World Series in 1984 and again in 1989, coupled with the revitalization of the Wrigleyville area, set them apart from their South Side bretheren. Wrigley Field came to be viewed as a monument to baseball history in a wonderful urban environment, while Comiskey Park was increasingly seen as an eroding structure in an uninviting part of town. The Sox indeed wanted to replace an aging ballpark, but more than anything the organization wanted to find a place that would allow it prosper beyond the shadow of the Cubs.

The failed referendum to bring the Sox to suburban Addison in 1986 sent the team into new home overdrive. The team started a serious flirtation with Tampa Bay elected officials that perhaps came even closer to fruition than the move to the suburbs. But the State of Illinois intervened and committed state funding to building a new stadium for the team in 1988. But with no new plan or site available, the Sox initially sought to replicate the suburban-style stadium proposed for Addison on parking lots just south of the existing Comiskey Park.

Many Sox fans were relieved the team would not leave its South Side base and abandon its identity, but were frustrated by the bland, out-of-character design. Baseball enthusiasts nationwide joined in. Soon, baseball fans began to rally behind an obscure proposal developed by Chicago architect Philip Bess. It put pressure on the team to think bigger.

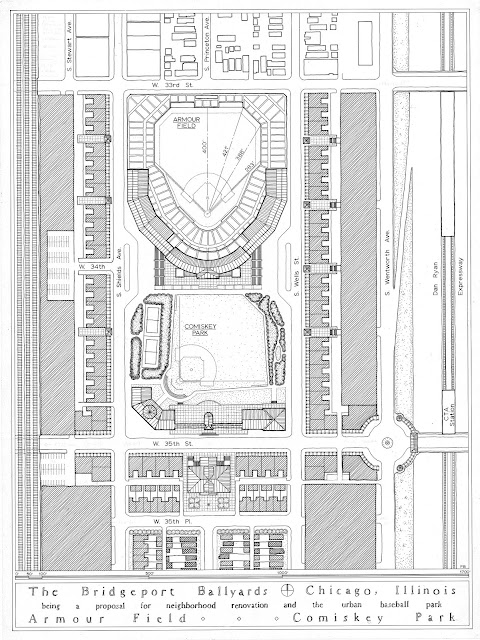

Armour Field was an audacious design that flew in the face of the cookie-cutter, multi-use stadium designs that dominated since the 1960's. It harkened back to baseball's heyday when ballparks were built into the fabric of surrounding community and accepted the constraints the built environment placed on it. Its overall height was kept reasonably low so as not to overwhelm the surrounding community. It occupied the small park known as Armour Square just north of Comiskey. Because of the site dimensions Bess designed a stadium reminiscent of the old New York Giants' Polo Grounds -- a U-shaped facility that brought fans close to the field action. The ballpark would have field dimensions that would go against the standardized scale that most MLB teams used then, with very short distances to the foul lines (just 283 feet), and exceptionally deep power alleys (421 feet to left-center and right-center fields). See the site plan below:

Armour Field site plan by Philip Bess. Source: http://afterburnham.com/armour-field/

Bess did a few other notable things as well. He replaced the lost parkland with new green space on the site of the old Comiskey including an outline of the old field. He included commercial areas near the ballpark to house restaurants, bars and other uses for fans. He placed a gateway at 35th Street and Wentworth Avenue, at the point that fans attending the game via the Red Line public transit would enter, to identify the location as a point of significance. And he added hundreds of residential uses, townhouses and multifamily structures, near the ballpark because he understood people would want to be close to the hubbub.

In 1989 the Sox and the State of Illinois sealed the deal for the new ballpark. It was great news for Sox fans and for the city, despite the huge public investment in the project. For the Sox organization, not so much. It meant starting from scratch again on the design, engineering and construction on the one site they were least wedded to, and it significantly pushed back the opening of any new facility. The Sox were hopeful, but not content.

Opening Day 1994 was a great day for the Sox and their new home; Armour Field was a hit from the start. The nostalgic look of the stadium gained admirers from across the country. The Sox set a new team attendance record of more than 3.2 million visitors. Armour Field's unique and historically pleasing design gathered tons of national attention. For the Sox it was a marketing success. Sadly, though, the labor dispute between the players and owners that culminated in the player's strike cut short a strong season by the Sox.

But the transformation of the Sox and the surrounding community began in earnest. The new ballpark and the revenues it generated meant the Sox began a transition from second-tier status to top dog in MLB. The Sox began to have a game day environment that rivaled the Cubs' Wrigleyville scene. The new residences were a catalyst for more development and renovation in the Bridgeport neighborhood. Amenities flocked to the area.

By the early 2000's Bridgeport became a neighborhood hotspot in Chicago. The area west of the ballpark between 31st and 35th streets received a huge influx of residents drawn by the Sox and the increasing recognition of the neighborhood's easy transit to the Loop. Revitalization soon spread to the northwest closer to Archer Avenue. Before long the entire area between Archer Avenue on the north, 35th Street on the south, the Dan Ryan Expressway on the east and Ashland Avenue on the west was transformed.

By 2005, Bridgeport was competing with Wicker Park as the hottest neighborhood in the Chicago -- at the same time the Sox ended their 88-year championship drought and won the World Series.

Transformation, however, came with a cost. Immense development pressure was placed on the small Armour Square neighborhood, also known as Chicago's Chinatown. Commercially Chinatown was as strong as it had ever been. But Chinatown leaders were deeply concerned about maintaining the integrity of their historic community.

East of Armour Field the story was quite different. At about the same time that the ballpark opened, demolition of the vast State Street Corridor public housing developments began. In 1999 the Chicago Housing Authority acknowledged the failure of its public housing developments and pushed to develop new, mixed-income developments. Before long, the Ickes, Dearborn, Stateway, and Robert Taylor developments were gone, with a promise of new development in the future. Many of the 20,000-plus public housing residents believed that the transformation of Bridgeport and the loss of their homes was no coincidence. There was considerable concern that the neighborhood investment they desired was all happening to the west of them. But there was fear that the terrible "G" word -- gentrification -- was about to rear its ugly head on former public housing land.

In 2014, after stinging criticism from South and West side community leaders following the closure of more than 50 public schools the year before, Mayor Rahm Emanuel announced that he would support a decking of the Dan Ryan Expressway between 31st and 35th streets with a 32-acre greenway that would connect Bridgeport on the west to Bronzeville to the east. The effort grew out of a partnership between the City, developers active in the Bridgeport area, Bronzeville leaders and activists and key institutions like Mercy Hospital and the Illinois Institute of Technology. Certainly the greenway would be viewed as a symbolic connection between adjacent communities often seen as being a world apart. But it was also viewed as an economic development catalyst that could ease development pressure on one side and stimulate investment on the other. The greenway began construction in 2016 and will open coinciding with this year's Sox Opening Day on April 4.

What started as a singular effort to help a moribund franchise gain a new home became something much, much larger. The effort leveraged the historical legacy of America's Pastime with the strength of committed local institutions and stakeholders, and promises to bring prosperity and opportunity to a long-neglected part of Chicago.

This piece originally appeared on The Corner Side Yard.

Pete Saunders is a writer and researcher whose work focuses on urbanism and public policy. Pete has been the editor/publisher of the Corner Side Yard, an urbanist blog, since 2012. Pete is also an urban affairs contributor to Forbes Magazine’s online platform. Pete’s writings have been published widely in traditional and internet media outlets, including the feature article in the December 2018 issue of Planning Magazine. Pete has more than twenty years’ experience in planning, economic development, and community development, with stops in the public, private and non-profit sectors. He lives in Chicago.

Photo: South elevation of the proposed Armour Field, looking north from 35th Street. The elevation and design proposal for Armour Field was done by Chicago architect Philip Bess. Source: http://afterburnham.com/armour-field/