It’s been a tough winter for those concerned about dynastic politics.

One-time First Daughter Caroline Kennedy is angling for a Senate appointment from the governor of New York. In Delaware Vice President-elect Joe Biden tapped a longtime aide as a placeholder for the Senate seat he will soon vacate, so his son, state Attorney General Beau Biden, will have a leg up in the 2010 special election. And an oft-mentioned Colorado Senate replacement for Interior Secretary-Designate Ken Salazar is his brother, Rep. John Salazar.

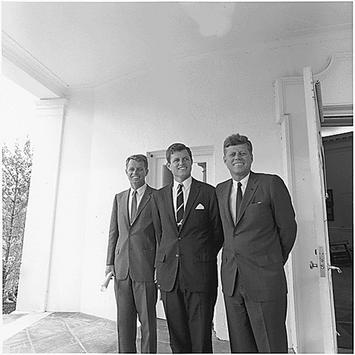

There’s nothing new about this story. Political dynasties are as old as the Republic itself. Our current president, 43, was elected just eight years after his father, the 41st, chief executive, was booted from office. The aforementioned Kennedys are an icon of American politics. In January 2009 the Senate will include a pair of first cousin freshmen lawmakers, Mark Udall (D-Colo.) and Tom Udall (D-N.M.)

The built-in advantages of political lineages are obvious. Voters, like, product consumers, are apt to go with a name brand. Moreover, parents or spouses in office can help raise campaign cash from contributors and lobbyists, thereby creating financial advantages early that can scare off primary opponents.

But political anti-royalists still can take heart that despite the best efforts of cunning pols and their operatives, voters have often rejected wannabe heirs to political thrones. The halls of Congress are full of lawmakers who beat kin and spouses of legislators who tried to keep their seats in the family.

Last month Republican John E. Sununu lost his New Hampshire Senate seat to the woman he defeated six years earlier, former Gov. Jeanne Shaheen. Sure, it could be argued that the younger Sununu might have never won high office in the first place were it not for a name strikingly similar to his father, former New Hampshire governor and White House chief of staff John Sununu. Still, in increasingly Democratic-leaning New Hampshire voters nonetheless bounced the political offspring at the first opportunity.

In North Carolina this year Sen. Elizabeth Dole of North Carolina also lost a Senate seat she had held for only one term. The wife of former Senate Majority Leader Bob Dole, the 1996 Republican presidential nominee, failed to impress Tar Heel voters with her performance. She had spent a minimal amount in North Carolina, preferring the comfy D.C. environs of her Watergate apartment. Her legislative record, meanwhile, was scant. Famous last name or not, voters went with Kay Hagan, a previously little-known state senator.

The House, too, is littered with the political bodies of defeated congressional relatives. There children of some of the highest-ranking and most influential politicians in the land have come up short.

Even a politician with relatively enduring popularity, former New Jersey Gov. Christie Todd Whitman, couldn’t help an offspring win high office. In June 2008 her daughter, Kate Whitman, sought an open House seat in the state’s bucolic central regions. But a famous name mattered little to voters, and on Election Day Whitman lost the Republican primary to veteran state legislator Leonard Lance by more than 20 points.

Or consider Scott Armey, who in 2002 sought the Dallas-area seat being vacated by his father, House Majority Leader Dick Armey. The younger Armey finished first in the Republican primary, but because he did not earn more than 50 percent, a runoff was needed. He ended up losing to Michael Burgess, a doctor and political novice whose literature reminded voters, “My dad is not Dick Armey.”

The same year, Brad Barton ran for the House in east-central Texas. He is the son of longtime Republican Rep. Joe Barton, who once served as chairman of the powerful Energy and Commerce Committee. Voters were unimpressed just the same, and the junior Barton finished third in his primary.

Most famously, political royalty did not assert itself in the 2008 presidential race. Former First Lady Hillary Clinton once seemed a shoo-in for the Democratic nomination. But Barack Obama, son of working-class Hawaii and lacking famous relatives, had other ideas. Soon the presidential spouse will be working for Obama, as his secretary of state.

Should Caroline Kennedy be appointed as Hillary Clinton’s replacement in the Senate, representing New York, she would certainly have advantages in name recognition and fundraising ability over political rivals, Republicans and Democratic primary opponents alike. But the recent history of political offspring and spouses does not mean she can expect voters to keep her around when they next get a say in the matter.

David Mark is a senior editor at Politico.com and author of Going Dirty: The Art of Negative Campaigning.