For more than a century, the city of Detroit has been an ideological and at times actual battleground for decidedly different views about the economy, labor and the role of government. At one time it was the center of a can-do entrepreneurialism that helped launch the American automobile industry. By 1914, for example, no fewer than 43 start-up companies were manufacturing automobiles in the city and surrounding region. Following a wave of sit-down strikes that began almost immediately after FDR’s landslide victory in 1936, the economic character of the city changed dramatically. Detroit soon became the quintessential union town, producing in the first decades after World War II the closest facsimile of Social Democracy that the United States has ever seen and in all likelihood will ever see again.

Detroit also specialized in race riots. In 1943, for example, a brawl that broke out at a popular getaway on a Sunday evening in June quickly escalated into mob attacks that resulted in the death of nine whites and 25 blacks. Because the white police force could not or would not restrain the violence, the mayor asked the governor to call in federal troops. Twenty four years and one month later in 1967, another Sunday riot broke out. This time most of the violence occurred between black residents and the police and National Guard. The death toll was similar, 10 whites and 33 blacks. Property damage, on the other hand, was far more extensive. Before the week was out, President Johnson appointed the Kerner Commission to make sense of the conflict and the growing unrest that was afflicting numerous cities all across America.

The next major event in the history of Detroit occurred in 1973, when Coleman Young was elected as the city’s first African-American mayor. He would go on to serve five terms. While clearly a reflection of the changing demographics in Detroit, Young also personified the city’s long history of union activism, having first gained prominence in the early 1950’s as the leader of the National Negro Labor Council. In the early 1980’s, in response to persistent economic decline, Young also led the fight to increase the city’s income tax, which included a tax on commuters. This signaled an important shift in progressive politics in Detroit and elsewhere. Rather than trying to wring additional revenue from private sector shareholders, labor and its political allies would now focus on the public sector as the preferred vehicle for income redistribution.

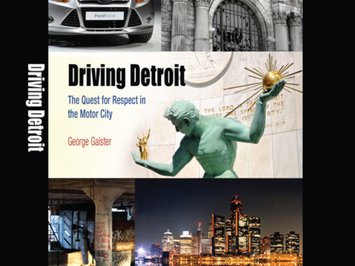

In Driving Detroit: The Quest for Respect in the Motor City, George Galster employs a multi-layered technique to bring the history of the city to life and help explain its current economic predicament. The title, for example, invokes the R&B classic “Respect” released by Aretha Franklin in 1967. Lyrics from other popular songs are also quoted, as well as a steady stream of poems by local Detroit poets. In addition, Galster weaves the stories of select individuals and families into the broader narrative that he constructs. At the very end, we learn that among the people we have gotten to know are his German-American parents and their forebears. And finally, Galster, who is the Clarence Hilberry Professor of Urban Affairs at Wayne State University, tries to explain the development of the city and region through what he calls geology, but in urban economics would more commonly be called geography. This may be the book’s most interesting contribution.

Galster emphasizes respect, which he defines as a combination of physical, social and psychological needs, because he argues that for many people in Detroit, for a long period of time, these needs were not adequately met. This was true for blacks, who faced racial prejudice. It was also true for factory workers, who historically had to endure dangerous working conditions, the monotony of the assembly line, and cyclical unemployment. The labor movement helped soften the sharper edges of factory work, but Galster shows that it was far less successful at promoting racial harmony. In part, this was a function of history. The largest boom in Detroit occurred during World War II, when the city was dubbed the Arsenal of Democracy. Because immigration had been stopped in the 1920’s, many of the new transplants came from the old South, often bearing well practiced well animosities. Solidarity in this context was difficult to achieve.

Along with the burden of history, another major challenge that Detroit faces today, surprisingly enough, is geography. In traditional terms, Detroit was an excellent place to build a city, located on a river that has never flooded and soon reaches Lake Erie. But in modern times, the local topography has proven something of a curse in disguise. Galster calls this topography a “featureless plain.” From the beginning, the city and region grew in a land extensive way. Assembly line manufacturing contributed to lower land use density, because efficiency required large, one story buildings. Typically, these factory buildings were interspersed among residential communities. This arrangement made for an attractive and prosperous lifestyle, but with de-industrialization, Detroit has not been able to fall back on a vibrant “old city” that could attract new and creative businesses.

So what kind of future can Detroit expect? Galster does not address this question directly, but clearly he appreciates the magnitude of the challenges at hand. The phenomena that characterize the metropolitan region are not unique, he says, but “Greater Detroit is distinguished by the intense degrees of all these phenomena and their special origins.” So perhaps the best take-away of Galster’s analysis is that the experience of Detroit should not be used to reach broad conclusions about the prospects of older industrial cities in general. Rather, it should be used as a cautionary case study. Detroit cannot alter its topography, but it can address problems like political chauvinism and sub-standard governance that Galster demonstrates have clearly had a negative impact on the business climate. Progress here in combination with a low cost-of-living and the revolution in natural gas production might then make it possible to attract the investment that the economy needs to re-invent itself. Certainly that would be the best case scenario.

Eamon Moynihan is Managing Director for Public Policy at EcoMax Holdings, a specialty finance company that focuses on the redevelopment of previously used properties.

most of today's jobs include

most of today's jobs include the use of technology, so it is very important that workers know how to use these technologies. One of the most common things that we might see today is the use of computer and special kind of machines. essay writers