In the last few decades, as suburbanization and deindustrialization devastated so many cities, they turned to two sectors that seemed not only immune to decline, but were actually growing: universities and hospitals. The so-called “eds and meds” sectors, often related through university affiliated hospitals, became a great stabilizer for many places. For example, the fabled Cleveland Clinic cushioned the blow of manufacturing decline in that city. Après steel, a city like Pittsburgh practically saw themselves as defined by an eds and meds economy, with the new economic pillars being the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center and Carnegie-Mellon University.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, these sectors have come to dominate so many cites' economic development strategies. It’s harder to find a major city that isn't touting some variation of a life sciences “cluster” as a strategic industry than one who is, and local medical schools and hospital complexes feature prominently in this. Similarly, technology transfer from schools is supposed to power startups, while in many cities growth in the number of students itself is supposed to be an engine of growth. For example, there are 65,000 students in the so-called “Loop U” collection of colleges in downtown Chicago, and education growth has been a bulwark of the Loop economy.

Yet in reality, overreliance on eds and meds is problematic. Firstly, these tend to be non-profit, and thus reduce the tax base in cities that are dependent on them. In danger of bankruptcy, Providence, Rhode Island was forced to ask for special contributions from Brown University and RISD, for example. Also, as quasi-public sector type entities, eds and meds are seldom a source to dynamism in communities in and of themselves. Indeed, universities are among the most conservative of institutions in many respects. Witness the firing and re-hiring of University of Virginia president Teresa Sullivan, for example, or faculty protests against the appointment of Indiana Governor Mitch Daniels as Purdue University’s next president due to his lack of an academic background.

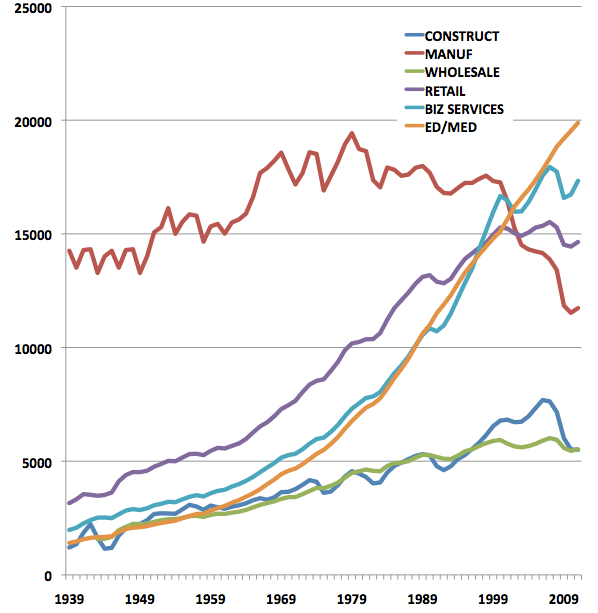

But for cities hanging their hat on eds and meds growth, a more fundamental problem now looms: these industries are at the end of their growth cycle. Spending on healthcare and college tuition costs has been skyrocketing at rates greater than inflation for years. Here’s a chart, via Atlantic Cities, showing job creation by sector since 1939:

If eds and meds employment has been going up continuously since 1939, what’s the problem? None, so long as it started from a low base at a time when other productive sectors of the economy were likewise growing strongly. But as sectors like manufacturing went into decline or stagnated, eds and meds has continued to increase relentlessly, accounting for an ever larger portion of total growth. For example, between 1990 and 2008, eds, meds, and government accounted for about 50% of all national job growth.

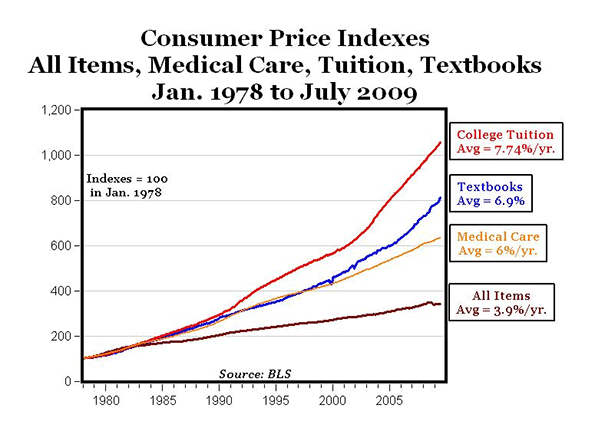

Unsurprisingly, with growth in jobs exploding, costs have followed. Medical costs and tuition have been growing at twice the rate of inflation, and at an increasingly divergent rate, as this chart from Carpe Diem shows:

Clearly, such a trend cannot go on indefinitely. As the US starts to groan under the weight of spending on health care and higher education, it's clear that, as a society, we need to be spend less, not more on these items as a share of national output. Some cities with unique strengths, like Boston, with its many specialized biotech firms, or Houston, with the world’s largest medical center, may thrive in this environment, but the vast majority of cities are likely to be very disappointed in where eds and meds growth will take them.

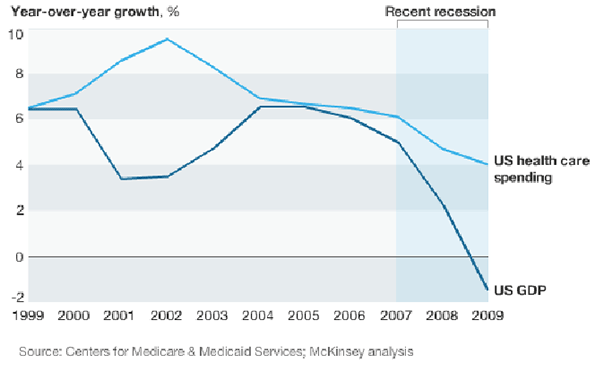

The problem with health care is most obvious. Aggregate spending on health care has been exceeding the inflation rate for many years. According to a report by McKinsey, spending on health care has consistently grown faster than GDP:

The net result is a sector that has been consuming an increasing portion of the national economy. Health care spending is projected to consume fully 20% of the entire US economy by 2021.

The health care reform act will do little to nothing to rein in this cost. It's difficult to see how in fact the trend will slow. But with the federal government (especially through Medicare) accounting for more and more total health care coverage, $16 trillion in national debt, and large deficits and unfunded entitlements, one can safely assume that whatever can't go on forever, won't. Eventually the government will be forced to take action to stabilize health care spending.

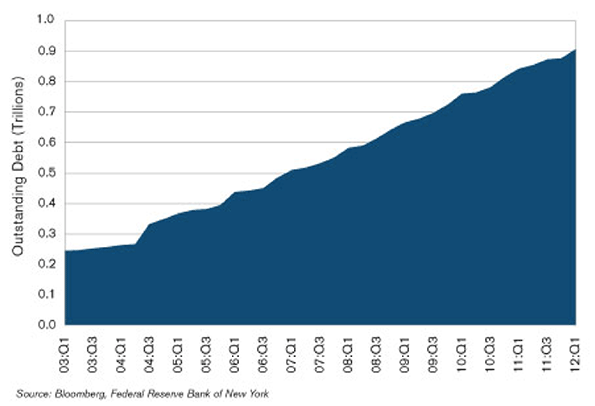

If the health care cost crisis has long been known, the public is just waking up to the crisis in higher education costs. Skyrocketing tuition has driven the cost of many colleges through the roof. This traditionally didn't bother students, who were assured that a college education the key to a good job that would easily allow loans to be repaid. In a global age where even knowledge economy jobs are subject to offshore competition, and a recession that's kept many young people --- including many now deeply in debt --- unemployed or underemployed. There is now about $1 trillion of it outstanding, much of it non-dischargeable in bankruptcy:

This student loan spike was created by many of the same dubious forces that led to the housing crisis. Indeed, some have said that student loans are the next subprime crisis, and commentators like Glenn Reynolds talk of a higher education “bubble”.

The overall economy will come back at some point, but it's clear that America is reaching the point at which it can no longer pile more debt onto the backs of students. This by itself will serve to moderate tuition increases at most institutions. There is also a significant amount of reform the current system obviously needs that, if implemented, would also tend to moderate tuition increases. For example, it doesn't seem unreasonable to suggest that colleges ought to have some skin in the game for these loans being repaid. Or that cheaper online education might substitute for physical classrooms in some cases.

Regardless of how it plays out, when you look at spending in aggregate in America, it's clear increases in health care and higher education spending cannot keep increasing at current rates. This means that it just isn't possible for all the cities out there dreaming of eds and meds glory to realize their dream. America simply can't afford it.

Whether the end of the great growth phase in eds and meds comes 1, 5, or 10 years from now can't be predicted. But come in the reasonably near future it will, and that's when the bulk of the cities that put all their chips in those baskets will receive a very rude awakening.

Aaron M. Renn is an independent writer on urban affairs and the creator of Telestrian, a data analysis and mapping tool. He writes at The Urbanophile, where this piece originally appeared.

Hospital photo by Bigstock.