To many observers, America's place in the world is almost certain to erode in the decades ahead. Yet if we look beyond the short-term hardship, there are many reasons to believe that America will remain ascendant well into the middle decades of this century.

And one important reason is people.

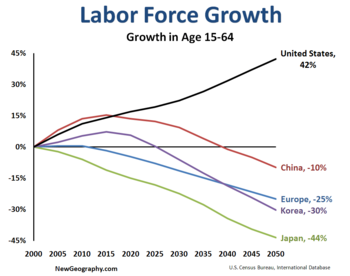

From 2000 to 2050, the U.S. will add another 100 million to its population, based on census and other projections, putting the country on a growth track far faster than most other major nations in the world. And with that growth -- driven by a combination of higher fertility rates and immigration -- will come a host of relative economic and social benefits.

More fertile

Of course the percentage of childless women is rising here as elsewhere, but compared to other advanced countries, America still boasts the highest fertility rate: 50 percent higher than Russia, Germany or Japan, and well above that of China, Italy, Singapore, Korea and virtually all of eastern Europe.

As a result, while the U.S. population is growing, Europe and Japan are seeing their populations stagnate -- and are seemingly destined to eventually decline. Russia's population could be less than a third of the U.S. by 2050, driven down by low birth and high mortality rates. Even Prime Minister Vladimir Putin has spoken of "the serious threat of turning into a decaying nation."

In East Asia, fertility is particularly low in highly crowded cities such as Tokyo, Shanghai, Tianjin, Beijing and Seoul. And China's one-child policy -- and a growing surplus of males over females -- has set the stage for a rapidly aging population by mid-century. South Korea, meanwhile, has experienced arguably the fastest drop in fertility in world history, which perhaps explains its extraordinary, if scandal-plagued, interest in human cloning.

Even more remarkably, America will expand its population in the midst of a global demographic slowdown. Global population growth rates of 2 percent in the 1960s have dropped to less than half that rate today, and this downward trend is likely to continue -- falling to less than 0.8 percent by 2025 -- largely due to an unanticipated drop in birthrates in developing countries such as Mexico and Iran. These declines are in part the result of increased urbanization, the education of women and higher property prices. The world's population, according to some estimates, could peak as early as 2050 and begin to fall by the end of the century.

Even more remarkably, America will expand its population in the midst of a global demographic slowdown. Global population growth rates of 2 percent in the 1960s have dropped to less than half that rate today, and this downward trend is likely to continue -- falling to less than 0.8 percent by 2025 -- largely due to an unanticipated drop in birthrates in developing countries such as Mexico and Iran. These declines are in part the result of increased urbanization, the education of women and higher property prices. The world's population, according to some estimates, could peak as early as 2050 and begin to fall by the end of the century.

Younger and More Vibrant

Population growth has very different effects on wealthy and poor nations. In the developing world, a slowdown of population growth can offer at least short-term economic and environmental benefits. But in advanced countries, a rapidly aging or decreasing population does not bode well for societal or economic health, whereas a growing one offers the hope of expanding markets, new workers and entrepreneurial innovation.

In fact, throughout history, low fertility and socioeconomic decline have been inextricably linked, creating a vicious cycle that affected such once-vibrant civilizations as ancient Rome and 17th-century Venice and that now affects contemporary Europe , Russia and Japan.

Within the next four decades, most of the developed countries in both Europe and East Asia will become veritable old-age homes: a third or more of their populations will be older than 65, compared with only a fifth in the U.S. By 2050, roughly 30 percent of China's population will be older than 60, according to the United Nations. The U.S. will have to cope with an aging population and lower population growth, in relative terms, but it will maintain a youthful, dynamic demographic.

More Hopeful About the Future

The reasons behind these diverging trends is complex. In some countries, a sense of diminished prospects, combined with a chronic lack of space, appear to be the root causes for plunging birthrates. As Italians, Germans, Japanese, Koreans and Russians have fewer offspring -- one recent survey found that only half of Italian women 16 to 24 said they wanted to have children -- they will have less concern for future generations.

In contrast, in the United States roughly three-quarters of young people report they plan to have offspring. Such individual decisions suggest that America, for all its problems, is diverging from its prime competitors, placing its faith in a future that can accommodate 100 million more people.

As author Michael Chabon recently wrote, "In having children, in engendering them, in loving them, in teaching them to love and care about the world," parents are "betting" that life can be better for them and their progeny.

This article originally appeared at AOLNews.com.

Joel Kotkin is executive editor of NewGeography.com and is a distinguished presidential fellow in urban futures at Chapman University. He is author of The City: A Global History. His newest book is The Next Hundred Million: America in 2050

, released in Febuary, 2010.

Photo: victoriapeckham