By Richard Reep

Investment in commercial development may be in long hibernation, but eventually the pause will create a pent-up demand. When investment returns, intelligent growth must be informed by practical, organic, time-tested models that work. Here’s one candidate for examination proposed as an alternative to the current model being toyed with by planners and developers nationwide.

Cities, in the first decade of this millennium, seem to be infected with a sort of self-hatred over their city form, looking backward to an imagined “golden era”. The most common notion is to recapture some of the glory of the last great consumerist period, the Victorians. During this time, from the 1870s to the early 1900s, many American towns and cities were formed around the horse-drawn wagon and the pedestrian. This created cities with enclaves of single-family homes and suburbs that seem quaint and tiny in retrospect to today’s mega-scale subdivisions and eight-lane commercial strips.

One bible for the neo-Victorians was “Suburban Nation,” a 2000 publication seething with loathing and anger over urban ugliness. In a noble and earnest effort to repair some of the aesthetic damage, the writers proposed a grand solution. Their goal was essentially to swing the development model back to the era of the streetcar and the alleyway, the era when cars were not dominant form-givers and families lived in higher density and closer proximity.

In the last decade, this movement gained traction with hapless city officials often tired of hearing nothing from their citizens but complaints over traffic and congestion. They embraced the New Urbanist movement which promised to turn the clock back to an era of walkable live/work/play environment of mixed neighborhoods. In the new model, the car would at last be tamed.

Yet, looking at most of these communities, the past has not created a better future. More often they have created something more like the simulated towns lampooned by “The Truman Show”. These neo-Victorian communities ended up with some of the form of that era, but devoid of employment and sacred space. They also created social schisms of low-wage, in-town employers and high-salary, bedroom community lifestyles marking not the dawn of a new era but the twilight of late capitalism as the service workers commute into New Urbanist villages while the residents commute out.

Meanwhile, planners who believe that practical design solutions and the vast quantity of remnants from the tailfin era are “almost all right” have remained quietly on the sidelines. This silent retreat, a natural reaction, now puts many good places in jeopardy as the activist planners try to “fix” neighborhoods and districts that were not broken to begin with. We risk losing some of the important postwar building form that well serves the needs of its users and, rather than being blacklisted, should be held up as a valid, comparative model for use by developers seeking to build good city form when the pent-up development demand returns.

It is time to hit back. Midcentury modern – the era from about 1945 to 1955 – has become a darling style of the interior design world, has yet to be recognized as a valid model for urban development. For too long, neighborhoods built in this era have been treated poorly by the planning community. Yet this period created a critical transition between the archaic beloved streetcar suburbs and the 1980s commercial car-must-win planning. They provide a valuable, forgotten lesson when the middle class’s newfound prosperity was expressed by low-density, car-oriented mixed-use districts that were still walkable and expressed through their form a certain heroic optimism about the future.

With building fronts set back just enough for parking, yet still close together to give a pleasant pedestrian scale, these little districts remain abundant in the landscape of our towns and cities – nearly forgotten in the fight over form, perhaps because they are doing just fine. They were built when everyone was encouraged to get a car, but before the car became a caveman club pounding our suburban form into big box “power centers” and endless, eight-lane superhighways of ever-receding building facades. These districts were developed before the local hardware store was replaced by Home Depot and many remain intact, thriving, and chock-full of independent business owners. Many of these are true mixed-use districts – with light industrial, second floor apartments, retail and other uses peacefully coexisting.

In small commercial districts developed in the late 1940s and early 1950s, a balance was struck between the traditional town form and the car, a balance that has been forgotten in the planning war being waged today. This era produced many neighborhoods and districts that are “almost all right”, in the words of noted Philadelphia architect and thinker Robert Venturi, when defending Las Vegas to the prissy academic community.

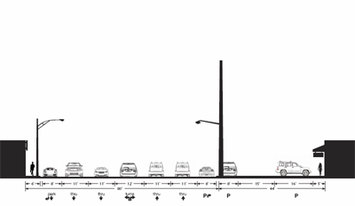

To go right to a case study, take the Audubon Park Garden District in Orlando, Florida. Adjacent to Baldwin Park, a Pritzker-funded New-Urbanist darling of 2002, this district is a vintage collection of mixed-use commercial, residential, and industrial buildings constructed in the 1950s. Set back from the curb approximately 42 feet, the mostly one-story storefronts allow parking in front yet are visible and accessible to pedestrians. The car is accommodated in the front of the store, making access easy and convenient, yet the pedestrian can walk also from place to place without long, hot trudges. Drivers see the storefronts. Scale is preserved. (See attached file for street elevations).

The architecture, instead of recalling nostalgic, Victorian styles, is influenced by the art deco and populuxe styles of the Truman era, when America was united, self confident, and victorious. And the businesses reflect an organic mix serving neighborhood needs, their storefronts and facades created by themselves, not by some Master Planner, theming consultant, or fussy formgiving designer. Here, one finds customers in dialogue with shopkeepers, blue collar and creative class mixed together, a few apartments over their stores, and a localism that has endured for fifty-odd years, largely forgotten because it works.

Places like this three-block district, and others like it, need to be championed. Decoding just what works here, and how it elegantly accommodates the car and the pedestrian, is critical to counterbalance the coercive impact of the New Urbanist movement and present a working model to future developers.

When New Urbanism was a fledgling movement, it represented a necessary alternative to car-dominated planning principles, and offered a choice where there previously was none. Today, the rhetoric of this movement has sadly forced out all other choices and emphasized one form – that of the streetcar era – over all others. This increasingly authoritarian movement shuts out all other choices today, and now threatens places like Audubon Park with its singular vision by sending in planners to “workshop” an ideal, Victorian makeover. Such actions, if implemented, will destroy the healthy, functioning connective tissue that makes up vast portions of our urban environment for the sake of a romantic notion of form over substance.

Instead of enforced, and often overpriced, nostalgia, we would do better to seek out districts planned after the car and have worked through time, and hold them up as valid choices to implement when planners are considering a development. These districts, whether a single building, a collection, or a whole community, will become important models as the pendulum swings back from the extremes that it reached by 2007 and 2008.

For too long, planners and developers have chosen to be silent in the face of the often strident rhetoric espoused by “smart growth” and New Urbanist ideologues. Meanwhile, a tough analysis of New Urbanism’s successes has yet to be seriously undertaken, and alternative models presented. Cities across the nation are considering a move to form-based codes which would lock out districts like Audubon Park and doom existing ones to Victorian makeovers. Useful, diverse and workable places will be destroyed to fit a “one size fits all” ideology.

So before midcentury modern becomes just another furniture style, a window of opportunity exists to fight back. These kinds of districts dot the cities and towns of America and deserve to be held up as alternative models for new development. Instead of a dogmatic slavishness to nostalgia, planners and developers need to stand up to the preachers of preapproved form, and look for multiple solutions for future urban form. Smart growth should not supersede the arrival of a more flexible, diverse approach of intelligent growth.

Richard Reep is an Architect and artist living in Winter Park, Florida. His practice has centered around hospitality-driven mixed use, and has contributed in various capacities to urban mixed-use projects, both nationally and internationally, for the last 25 years.

| Attachment | Size |

|---|---|

| Audubon_street_elevations.pdf | 3.49 MB |

Just viewed the streetview

How is this remarkable? This looks like any other unpleasant eyesore, and pedestrian/bicycle nightmare. It's development for cars, not for people. If my car needs a nice place, I'll make sure and refer it there. for me, I'll pass.

My problem with New Urbanism

is not that it is Neo-Victorian, but that it is too uniform and too controlling.

I believe that urban success is more an organic process than a designed process. The NU practitioners are all about control and uniformity. I find their "artwork" to be very boring. Can you imagine a NU acolyte allowing a "Gene’s Automotive" to exist as it does in the Audubon Park Garden District? No way, no how.

My prediction is that most of NU developments will fail. As all the buildings in a development were built on the same day, they will all die on the same day. The controlling rules won't let a natural occurrence of Class A thru Class D commercial space develop. NU idiots think it can all be Class A all the time. Wrong!

Dave Barnes

+1.303.744.9024

http://www.MarketingTactics.com

If you actually read the NU

If you actually read the NU codes being adopted in existing towns and cities, Dave, you would find them substantially less controlling and uniform than the traditional zoning that preceded them. See the Peoria Ill. land development code adopted in 2007. Even Suburban Nation, published in 2000, talks about accommodating class A and B commercial space, where class B is defined pretty broadly to include things like auto repair garages.

I agree that the greenfield TNDs that NU has produced so far are mostly about producing the "planned picturesque", and to do so they've been pretty controlling. Partly this is because suburban residents want a large degree of uniformity in their developments, and, as I said before, these were prototypes designed to prove the demand for traditional walkable urbanism. If you can produce any evidence that TNDs are performing worse than standard subdivisions I'd like to see it. Now older existing places have been willing to adopt NU-inspired form based codes, which allow for a much more "organic" process of growth. You should take some time to read them before dismissing their authors as a bunch of idiots.

Unfair criticism of NU

This criticism of NU is similar to the one Alex Marshall made in his book "How Cities Work". This book, though, was published almost 10 years ago when the criticism was more fair - at that time, Duany and the New Urbanists could only point to greenfield TNDs as showcases for their principles. Kentlands et al were too small of course to impact regional transportation or employment patterns, with the result that they functioned as stylized garden suburbs, not as real urban centers. Even 10 years ago, when the criticism was correct in a strict sense, it was more than a little unfair, for how else was the NU movement supposed to get off the ground? Without small greenfield "prototypes" to prove the market, NU developers could never persuade city planning boards, financiers, and the public to support their vision at a larger scale, which is necessary to change how cities actually work, not just how Victorian they look. Now that entire cities have adopted NU-inspired comprehensive plans, most notable among them Miami, we can judge more fairly how NU works at the macro scale.

You also ignore "west coast" New Urbanism which has been thinking regionally for longer than east Coast NUers like Duany and is certainly not wedded to Victorian architecture (Nor really, is Kentlands MD, which is mostly colonial/federalist. Ditto New Daleville, PA. Exactly where is the evidence that NU design must be victorian anyways?). See Calthorpe's "The Next American Metropolis" published in 1993. There is ample evidence that east coasters have been incorporating these ideas more recently, if you look at transect based codes or the Smart Growth Manual. Rather than representing a "dogmatic slavishness to nostalgia", NU thought is trending towards accommodating more flexibility and diversity across the region. There would be nothing contradictory about a NU form based code allowing for art deco design, or for allowing parking in front in some areas. It is certainly not a "one size fits all" ideology, your unsubstantiated assertion notwithstanding.