Korea’s success, to date, in limiting the spread of the new coronavirus without extensive lockdowns has been widely acknowledged. A May 6, 2020 Atlantic article provides an excellent description of the “trace, test and treat” system employed here. The text messages used to trace new infections are even more detailed than described. The messages are still reassuring, particularly in light of the new cluster of cases in and near Seoul [attributed to a club-hopping infected individual]. They communicate a strong message that the authorities are doing everything reasonably expected to stay in command of the situation.

The same Atlantic article, so helpful overall, takes special pains to caution against attributing Korea’s success to anything other than the experience the country gained through the mistakes made during two previous public health crises, the SARS outbreak in 2002-2003 and MERS in 2015. Attributing Korea’s success to aspects of the country’s culture is racist in the author’s view; Korea’s success, he concludes, is “not the product of religion, or cultural destiny, but rather the result of diseases bested and crises weathered.” To think otherwise will prevent other countries from learning from Korea’s example.

But if the rise of East Asia the past half century tells us anything, it is that culture matters. After all, Korea and other Asian countries’ rise was not the product of conquest, favorable location on trade routes or concentrations of valuable natural resources. It may be offensive to suggest this success came from “an ancient culture of docile collectivism and Confucianism,” but the fundamental values are critical to understanding how Asian societies have been able to adjust to the pandemic. To be sure, other cultures outside Asia can adopt some of Korea’s model, but the cultural predicates are critical.

In Confucian thinking, a well-ordered state and cultivated individuals are mutually dependent. One cannot exist without the other. The Great Learning is where beginners have always started. Paragraph 4 of this work, regarded as a key text in the Confucian school, makes this interdependency clear. In Korea, the more or less satisfactory resolution of competing interests, hard work and citizen cooperation necessary for any undertaking of this magnitude were made possible by a general recognition that the coronavirus crisis, as frightening as it was, also provided another opportunity for Korea to show the world how a medium-sized country of 51 million with a nominal GDP roughly the same as Texas’ could punch way above its weight. That, in turn, matters immensely because, in the Confucian mind-set, a country’s success reflects the cultivation and rectitude of its individual members.

Korea is not unique in this respect. Routine trade disputes in the 1980s were derided as “Japan bashing” in that country. And Chinese commentators today bristle at anything that “insults China.” President Trump, in referring to the “Wuhan” or “Chinese” virus, failed to understand this, or understood it all too well. The identification of individuals with their state is hardly unique to East Asia. In Plato’s Crito, Socrates was quick to distinguish between well-governed cities and the disorderly places he had no desire to call home. Many Americans still take pride in being citizens of a nation thought of as having a distinct mission. But many Koreans have an equal or even stronger sense of exceptionalism, which has been on display throughout this crisis.

Experience with the prior outbreaks did not by itself assure success with the new coronavirus. Equally important was a foundation built on general good health and high educational achievement. Both have deep cultural roots. The hard work in a Confucian-influenced society begins, again, with cultivation of the individual, not the community. Among its features, at least in Korea today, is a near obsession with personal health. Health concerns helped shape an excellent, though not perfect, medical establishment that is accessible to almost everyone, is at once closely regulated and highly competitive, and focuses on preventative medicine. Life expectancy at birth is 82.7 years, among the highest in the world; Koreans consult doctors on average 16 time per year, more than twice the OECD average; health screenings for early detection of common diseases are usually free.

The desire for individual cultivation also supports a vast public, private and commercial educational system that keeps students, at least in normal times, in classrooms almost every waking hour. The country consistently ranks in the top ten in all subjects measured by the OECD’s Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA). Approximately 70 percent of 24-35-year-olds have completed tertiary education of some form, according to the OECD. Excellent but not perfect (many middle-class families struggle to pay for extensive after school instruction; not all college graduates find employment commensurate with their education), it produces citizens who are by and large inquisitive and very well informed.

Individual cultivation has become somewhat suspect as “victim bashing” among western progressives as it seems to ignore the systematic unfairness said to make self-improvement difficult or impossible. But many Koreans combine a strong sense of individual responsibility with deeply felt grievances, sometimes personal, often collective and of long standing. Each spring brings commemorations, recriminations and debate over the March 1st Movement (1919), the “comfort women” dispute with Japan (-1945), civilian massacres on Cheju Island (1948-1949) and in Gwangju city (1980), and the tragic sinking of the Sewol ferry (2014). Docile and serene are not apt descriptions of this society. The lesson here transcends the COVID-19 pandemic. People can strive to improve themselves and their lot without forgetting or giving a pass on injustices that have impeded them.

It is not that Korea does not suffer from incompetency and alleged self-dealing --- this doomed former President Park Geun-hye --- and helped bring current President Moon Jae-in into office. Yet when governments are run according to meritocratic principles --- the bureaucracy has to sit through difficult examinations --- they can assume, with widespread support, unusually strong powers. The meritocracy is open, to an extent Americans can envy, to almost everyone. But everyone has to play by the rules. The idea is very Confucian.

The Atlantic article also states that Korea’s politicians let the health ministry do the talking, and invites its readers to imagine U.S. briefings with no members of the White House present. Korean health officials do indeed appear almost every evening on the news, but the president appears as well, along with the prime minister and, with the recent outbreak in Seoul, that city’s mayor. They have to. Competent ministers are the key to a well-managed state, but the head of state has to lead --- as failed leaders, like former President Park, learned the hard way in her much-criticized handling of various domestic crises.

To ignore culture is also to miss out on much that is interesting about other societies. Briefings by health officials and political leaders alike here have a formal aspect (“ceremonial” does not quite capture it). Korean politics can be a blood sport and the combatants sometimes wear their respective party colors, particularly during elections. The president’s party wears blue or uses that color in its sloganeering, the main opposition invariably wears or employs red. But everyone, regardless of party or position, dons the same off-yellow windbreaker for briefings and in most personal appearances. The same jackets are worn in other emergencies. Westerners sometimes dismiss this kind of thing as empty ritual, but this actually reflects deep Confucian roots. Observing the proper form helps assure the audience that matters are being properly handled, that the people in charge are putting aside their own interests, on this matter, for now, for the common good.

The online version of the Atlantic article described above contains a link to an earlier essay on America’s own response to the coronavirus. That author attributes the U.S.’s failures almost entirely to its culture of individualism, contrasting, in the words of an academic quoted there, the “solidarity and trust” in states seen as “smart and generous and honest and competent” with America’s “market-based, hyper-individualistic system organized around distrust and fragmentation.” The contrast is overstated. President Moon enjoys a great deal of solidarity and trust, on this issue and for the present, but it was hard won and will evaporate overnight if the measures he has overseen fail or if the economy, dependent heavily on exports and with a large and vulnerable small and medium industry sector, weakens as a response to the emerging recession.

Taken together, the two Atlantic pieces and articles like them employ an odd and perhaps condescending double standard. Success abroad is a cultural orphan but U.S. failures have many fathers, at least where the coronavirus is concerned. If we are all to learn from this crisis, then culture either counts for everyone or not at all.

The better course would be to consider potential cultural factors in an informed and well-meaning way. There is a good deal of truth to the assertion that greater individualism has hampered America’s response to COVID-19. Almost everyone on our campus and in our city wears masks, even families at the beach with a near gale blowing in off the sea and solo hikers in the hills behind our school. The few without masks are mostly Westerners. They do not draw comment, at least directly, but the sight is disconcerting. Why this insistence on a right so trivial and so at odds with an obvious communal norm in a place they have chosen to be?

If cultural strengths and weaknesses are to be considered, the implications and potential benefits extend well beyond the new coronavirus. Thoughtful people are already considering them. The first two chapters of a recent work, Confucianisms for a Changing World Cultural Order, are excellent examples. The first outlines a Confucian critique of global capitalism. The second calls for a dialog between Confucianism properly understood and what the author describes as the liberal self-centeredness characteristic of Western societies. One can disagree with some of the points made, but a debate would be worth having.

Nor would the exercise be a one-way street, with East schooling West, or vice versa. Traditional Confucianism jumps directly from the family (or friends) to the state, with few references to what Westerners would think of as civil society – the multiple communities of voluntary association that bring individuals together apart from government. To be sure, Korea has its churches and labor unions, but they exist mostly to benefit their immediate members. Beyond family and a tight circle of friends or classmates, categories with considerable overlap, and short of the nation state, others are usually kept at a polite distance, with less sense of community than many Americans take for granted. Family formation, Confucian bedrock, has declined precipitously in Korea, which creates opportunities for positive cultural exchange. [Our small, mostly American law faculty has played a modest role here. All but one professor is married, two for more than 40 years. Nine professors and their spouses are parents of a total of 36 children. Our students notice. We celebrate a lot of weddings and an increasing number of new births.]

No culture has a monopoly on civic virtue. All of us can learn, and the coronavirus disease provides an excellent opportunity to do so.

Edward Purnell is a professor at Handong International Law School in Pohang, Republic of Korea. Before teaching, he practiced law in Chicago. He served in the U.S. Peace Corps (Korea) immediately after college.

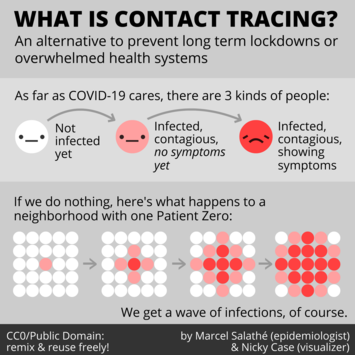

Graphic: Marcel Salathé and Nicky Case via Wikimedia under Public Domain