The newly published US Census Bureau state and District of Columbia population estimates contain some surprises about changing growth and net domestic migration (movement between states) patterns.

Perhaps the most significant shifts are declines in net domestics migration to states that have long benefited from population growth from California. Washington, Colorado and Oregon now are seeing their own domestic migration rates plummet since the beginning of the pandemic. In contrast, other states to which many Californians and others have fled — such as Texas, Arizona, Idaho, Nevada, Utah, Florida and Tennessee — continue to display strong attraction.

Moving Away from California

The outmigration of Californians has been substantial. Each annual population estimate by the US Census Bureau at least since 2000 has shown net domestic outmigration. The total of these more than two decades of report is that nearly 3.5 million more Californians have left for other states than have moved into California. This is more people than live in any of the nation’s cities (municipalities), except for New York and Los Angeles. That’s also more people than live in 31 states.

More recently, there is considerable evidence that the exodus of households from California has been joined by a large number of corporate relocations to other states, according to a Hoover Institution report.

Reverses like those long evident in California, but now also in Washington Colorado and Oregon are not unprecedented. There was a time, in the not too distant past, that California was not only the largest state, but also routinely the one that gained the most population. As late as 2007, the California State Department of Finance projected that the population would reach 60 million by 2050. However, growth soon stalled, and the present projection anticipates 44 million by 2050, more than a quarter lower than previously projected.

By the early 2000s, net domestic migration losses from California were already occurring, and were to become much larger. Just in the last two years, the net domestic outmigration was more than 800,000 — nearly equal to the population of the city of San Francisco (815,000 in 2021).

Why have so many people left California? Multiple reasons have been suggested. The state’s high cost of living, driving by its far higher than average housing costs may be the most important. For example, in its seven major metropolitan areas (Los Angeles, Riverside-San Bernardino, San Francisco, San Diego, Sacramento, San Jose and Fresno) only from 4% to 15% of houses are affordable to median income families, according to the NAHB/Wells Fargo Housing Opportunity Index. In other words, the median income family cannot afford a middle income lifestyle.

In the United States, even including the high prices of California, the overall average of houses affordable to the median income family is at least three times as high, at 42%.

Higher taxes and higher gasoline prices have also been cited. State and local public policy is an important determinant of the differences in housing costs, taxes and gasoline process with other states.

Washington, Colorado, and Oregon

In the last two decades, Washington, Colorado and Oregon attracted more than 1.6 million net domestic migrants, according to Census Bureau data. Yet, in the past two years, the three states lost a net 15,000 residents to other states. This compares to an average annual net domestic migration gain of more than 80,000 between 2000 and 2020.

Among the three, Washington is the most populous, with 7.8 million residents. Between 2010 and 2015, Washington was among the 10 states with the highest net domestic migration rates. By 2022, it had dropped to 26th. Washington peaked at a net domestic migration of 68,000 in 2016. By 2021, it had dropped to net domestic migration outflow of 15,000, and a minus4,000 in 2022. These were the first two domestic migration losses for the state reported by the Census Bureau since at least 2000.

Colorado, with 5.9 million residents was also among the 10 largest recipient states in net domestic migration, through much of the 2010s. The peak came in 2015, at 57,000. By 2021, net domestic migration had dropped to 5,700 and then to 5,400 in 2022. In 2022, Colorado’s net domestic migration rate had dropped to 21st.

Oregon is the smallest of the three, with 4.2 million residents. Like Colorado and Washington, Oregon was among the top 10 net domestic migration destinations earlier in the 2010s. Oregon peaked at a net domestic migration figure of 51,000 in 2016. By 2021, net domestic migration had fallen to 10,000, and then further, to a minus 17,000 in 2022. Oregon ranked 41st in net domestic migration in 2022. These were the first net domestic migration losses for the state reported by the Census Bureau since at least 2000.

Further, Oregon’s 2022 population is slightly below that of two years ago.

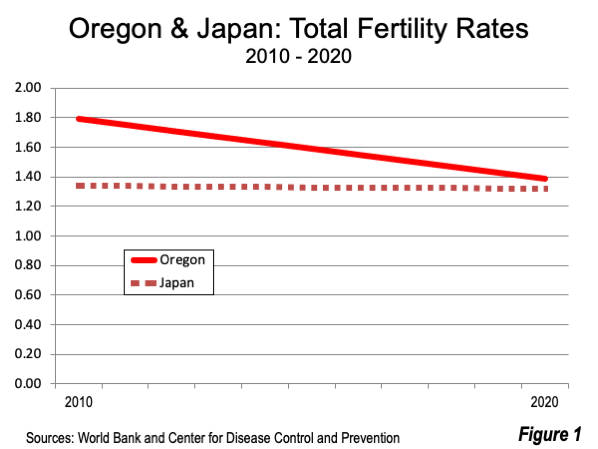

In addition, Oregon, unlike Washington and Colorado had a net decline in natural growth, with deaths exceeding births by 5,100 in 2022 and 2,200 in 2021. Oregon’s lagging total fertility rate (TFR) contributes to this. Oregon’s 2020 TFR was reported at 1.39 by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, having dropped from 1.79 in 2010. The TFR estimates the average number of live births by each woman, with 2.10 required to retain the same level of population. Japan, is legendary for its low TFR, (now at 1.32, according to the World Bank), and is declining slowly by comparison to Oregon. Oregon could be poised to drop below Japan’s TFR in the near future (Figure 1).

With their far smaller populations, Washington, Colorado and Oregon are unlikely to rival the net domestic migration losses of California. But all three states could be facing a future of substantial out migration.

Following the California Model

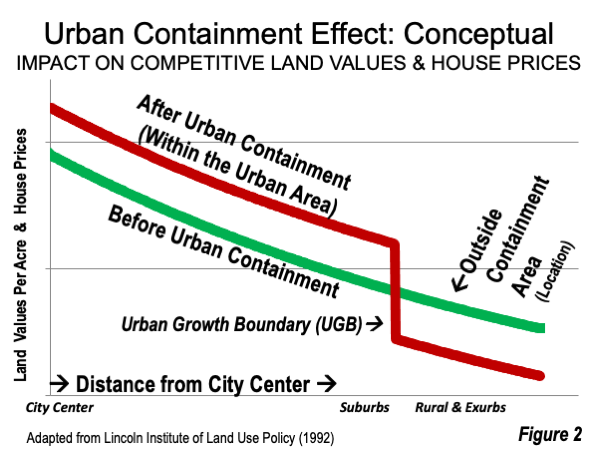

What do these states have in common that could be deterring inbound migration?Policies that make housing more expensive are at least part of the answer. For about five decades, California has made it more difficult (read: more expensive) to build new houses, along with state, regional and local urban containment policies that have been associated with grossly inflated land prices (and house prices) by rationing land for development on the urban periphery (Figure 2) and its overly strong statewide environmental regulation (the California Environmental Quality Act, or CEQA) London School of Economics Professor Paul Cheshire has shown that urban containment policies are irreconcilable with housing affordability and price stability. The major metropolitan areas of Washington, Colorado and Oregon have urban containment policies and have seen their house prices rise far more in relation to incomes than nearly all other states.

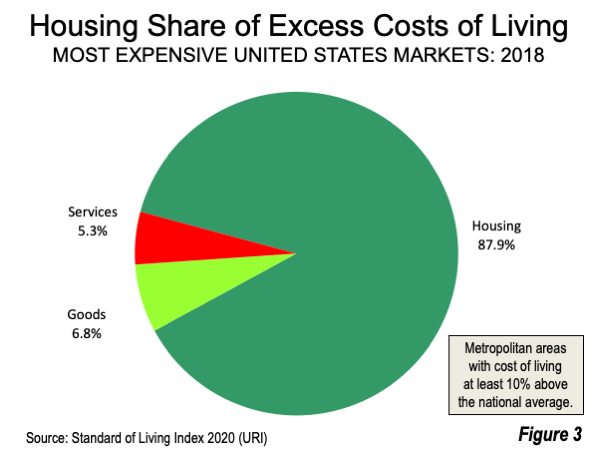

Differences in the cost of living largely reflect housing cost differences (Figure 3) and the three major metropolitan areas (housing markets) of Washington, Colorado and Oregon have seen about a doubling of their median house prices relative to median household incomes in the last quarter century. Middle-income households are less likely to move to where a middle-income lifestyle cannot be afforded.

Wendell Cox is principal of Demographia, an international public policy firm located in the St. Louis metropolitan area. He is a founding senior fellow at the Urban Reform Institute, Houston, a Senior Fellow with the Frontier Centre for Public Policy in Winnipeg and a member of the Advisory Board of the Center for Demographics and Policy at Chapman University in Orange, California. He has served as a visiting professor at the Conservatoire National des Arts et Metiers in Paris. His principal interests are economics, poverty alleviation, demographics, urban policy and transport. He is co-author of the annual Demographia International Housing Affordability Survey and author of Demographia World Urban Areas.

Mayor Tom Bradley appointed him to three terms on the Los Angeles County Transportation Commission (1977-1985) and Speaker of the House Newt Gingrich appointed him to the Amtrak Reform Council, to complete the unexpired term of New Jersey Governor Christine Todd Whitman (1999-2002). He is author of War on the Dream: How Anti-Sprawl Policy Threatens the Quality of Life and Toward More Prosperous Cities: A Framing Essay on Urban Areas, Transport, Planning and the Dimensions of Sustainability.

Photo: Downtown Seattle, largest business district in the three states of Washington, Colorado, and Oregon. By Daniel Schwen via Wikimedia under CC 4.0 License.