You could say that Ventura County, just north of Los Angeles, represents what is best about California. Some people believe that its amenities – beaches, gorgeous interior valleys and parks – assure perpetual economic growth for Ventura County and California. They are wrong. There is trouble in paradise.

Ventura County has changed, and not for the better. It is aging, losing its demographic as well as economic vitality. This represents a relatively new phenomenon, the slow decline of even formerly healthy suburban areas.

The current recession illustrates the change. In the past Ventura County suffered mild recessions even as the country and the region suffered mightily. The County saw no annual net job losses in the 2001 recession. The early 1990s recession was more painful, but Ventura County did far better than California as a whole.

All of that has changed with the current recession. Ventura County has recently been losing jobs at a faster pace than California. In 2007, the County lost jobs while California gained jobs.

The picture is even worse when Ventura County’s economy is compared to the Los Angeles County economy. In 2008, Ventura County’s economy shrank at a rate about five times faster than did Los Angeles’s economy.

What is going on here? In the past, Ventura County has been buffered by its twin giants, Amgen and Countrywide. Amgen’s Ventura County growth has slowed. Countrywide has done much worse than Amgen, and its demise has been well documented.

But you can’t blame all of Ventura County’s weakness on Countrywide. It has contributed, but it is not Ventura County’s sole source of economic weakness. The weakness is quite general, spanning the construction sector, non-durable manufacturing, retail trade and other services. Each lost over 1,000 jobs in 2008. By contrast, the finance, insurance, and real estate sectors, where Countrywide resides, lost just fewer than 900 jobs, accounting for about 4 percent of the job losses.

My sense is the real underlying problem is demographic, and this may not go away even if the economy recovers. One clue is that more people have been leaving Ventura County than moving in from all sources, and this has been happening long enough to be a trend. It reflects still-high housing costs and limited opportunity. It implies a weak future.

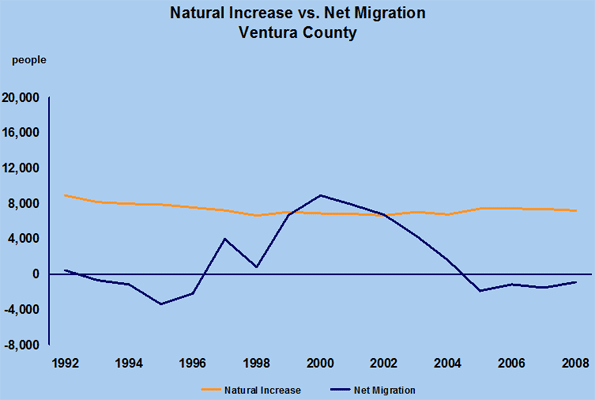

This chart shows that in exactly half of the past 16 years, migration has been negative. That is total migration, not just domestic migration.

Think about this for a moment. More people are leaving Ventura County than are moving in. That is certainly counter to what has happened in most of the past 150 years.

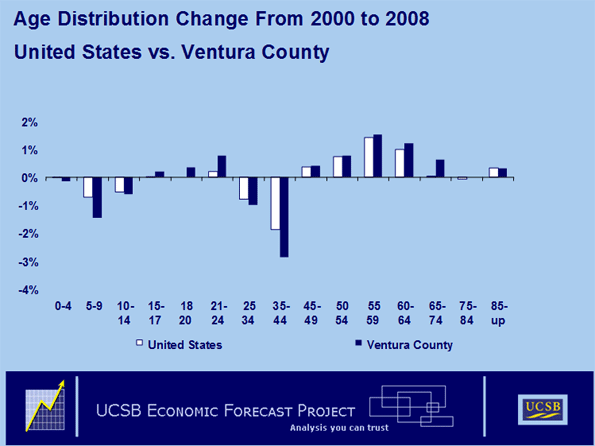

Ventura County’s net out migration has impacts beyond its effect on the size of the population. The composition of the county is also changing, away from working age people and families and towards people either close to retirement or already there.

The above chart compares relative changes, by age cohort, in Ventura County’s population since the 2000 census with changes in the United States population since the 2000 census. The County’s population between 25 and 44 years of age and their children has been collapsing. At the same time, the County’s populations of both young adults and people over 45 have been growing as a percentage of the total population. The bulk of that growth has occurred in the over 55 cohort.

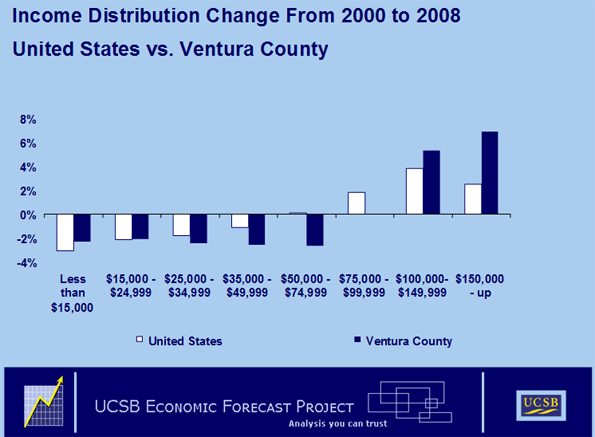

The migration out of Ventura County has also resulted in changes to the County’s income distribution. The following chart compares changes in the County’s income distribution to changes in the United States income distribution since the 2000 census:

The comparisons are telling. The County has been losing very-low-income people at a slower pace than has the United States. At the same time, the growth in population with incomes over $100,000 has been spectacular. The local population with incomes between $25,000 and $75,000 has fallen far more rapidly than that of the United States. The County’s population with incomes between $75,000 and $100,000 is relatively unchanged, while that of the United States has shown significant growth.

People – particularly in the late 20s and early 30s – aren’t leaving Ventura County because amenities have suddenly disappeared. They are leaving because of a deficit in opportunity. Their leaving has consequences. Ventura County’s population is aging more rapidly than it otherwise would. The net result of these demographic changes is that Ventura County’s median real per-capita income is declining, while the County’s median age is rising. Real per-capita personal income has fallen almost $1,000 in only eight years, to $32,718 (Constant 2000 dollars) from $33,797 in 2000.

Ventura County’s demographic changes can be easily summarized. It is losing its middle class and becoming bi-modal. The young families that provide a community’s vigor and future have been leaving. There is no reason to believe that the trend will reverse itself. Ventura County home prices are still relatively high, while opportunity is declining.

The County is left with an aging and increasingly wealthy population along with the lower-income people that service the wealthy aged and the very-low-income farm workers. In a sense, it now resembles what we see in many expensive city cores – even if it is on the periphery!

This creates enormous risks. Most amenities are luxury goods. Poor people don’t invest in luxury goods. Generally, the lower-income population does not have the resources to provide leadership or invest in a community’s future. They have their hands full just taking care of their families, particularly in an expensive place like Ventura County. Their children will likely join the middle class, but in someplace more affordable like Texas, Arizona, or Nevada.

High concentrations of older people and declining incomes are often associated with deteriorating schools, amenities and increasing crime. The aged wealthy are not in Ventura County to invest in its future. They are there to consume it. They will not invest in the future – particularly if their children and relatives have gone elsewhere.

Ventura County is not unique. It is fairly representative of Coastal California. Communities like Ventura, Goleta, and San Luis Obispo used to be middle-class communities that valued opportunity. Things are even more extreme in California’s elite playgrounds: Monterey, Malibu, and Santa Barbara. Populations in Monterey and Santa Barbara have actually declined over the past several years. Similar phenomena may be noticeable in other formerly elite suburbs within our most favored metropolitan areas.

These changes present serious challenges to California’s workers, businesses, and those policy makers who still care about something other than greenhouse gases and public employee pensions. Something needs to be done, and quickly. But the immediate prognosis is less than encouraging. Like Ventura County, California is suffering its worst recession in decades, and policy makers don’t seem to be focusing on policies that may help the area return to its previous status as a region of opportunity.

Portions of this essay have previously appeared in a UCSB-EFP Ventura County Forecast.

Bill Watkins, Ph.D. is the Executive Director of the Economic Forecast Project at the University of California, Santa Barbara. He is also a former economist at the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System in Washington D.C. in the Monetary Affairs Division.