The Trump Infrastructure plan has finally been released. The critics are out in force, especially those with particular interest in rapid transit. The plan would reduce funding to the federal “new starts” program, which provides funding for new urban rail and busway systems. The Los Angeles Times editorial board expressed angst at this proposal. According to The Times, the "…public transit building boom in L.A. County relies on federal funding that would be slashed under the president's infrastructure and budget proposals. The Purple Line subway to Westwood was slated to receive more than $1 billion, or roughly 45% of the total cost, from the federal government. Without that money, it will be extremely difficult to complete that project, as well as others, in time for the 2028 Summer Olympics in Los Angeles.”

The Times needn’t worry. The experience in Los Angeles suggests that even with the nation’s worst traffic congestion, a concerted effort can sufficiently reduce traffic congestion and that buses alone can provide sufficient levels of high-quality, transit service for the Olympics.

1984: The Catastrophic Traffic that Never Was

In the early 1980s, as today, Los Angeles had the worst traffic congestion in the nation. The largest venue, the near 100,000 capacity Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum, is located near where the traffic is the worst, just a few miles south of where eight freeways converge on downtown, both an important destination, but a chokepoint for travel between the widely dispersed business centers and residences throughout the metropolitan area. As bad as it was, the average Angeleno managed to travel less than 30 minutes to work.

There was considerable concern that the gridlock always imagined by the press would occur. It did not.

To the contrary, traffic conditions improved (See: 1984: The Year of Catastrophic Traffic that Never Was). A Southern California Association of Governments (the Los Angeles area metropolitan planning organization) noted the surprising events: “Were you in Los Angeles during the “Olympics Miracle”? Did you like the absence of traffic jams and freeway congestion?” The publication continued: “What happened? People modified their work schedule and stayed off the roads at normally peak periods. Truckers changed their delivery schedules to avoid peak period traffic. … The result was that more people were travelling in the region, but traffic congestion was much lower than normal.”

Companies around Southern California established programs to advise employees of transportation alternatives, including alternate routes (I managed the corporate program for my then employer, Crocker National Bank, which was later absorbed by Wells-Fargo). Companies allowed more people to take vacations during the period and there was greater use of flexible work schedules.

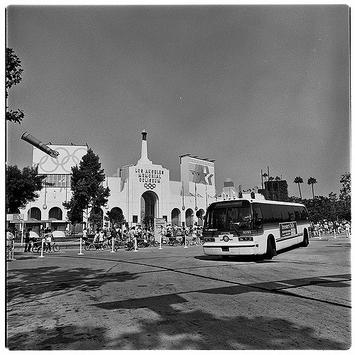

Successfully Serving the 1984 Olympics with Buses

In 1984, there was great concern that for the first time since 1960, the Summer Olympics were being held in a city that did not have a regional rail transit system. Local transit planners at the Southern California Rapid Transit District (SCRTD), the operating predecessor to today’s Metro, set about to solve the problem. They designed an extensive Olympics bus system that served the Olympics venues around Southern California. From an operational perspective the system worked well, with 40 percent of Olympics spectators using the buses. As the video below indicates, customers were very happy with the service.

Video: A Gold Medal Performance for Public Transit

Coincidentally, the Olympics were held in fiscal year 1984-5, when SCRTD set an all time SCRTD-MTA ridership record of 497 million riders (1,000,000 of whom rode the Olympics service). With the huge ridership losses since that time, and despite the rail building boom, there are now likely to be many more empty seats to carry Olympics passengers.

Transportation in Los Angeles: Up to the Challenge

More than three decades later, despite the massive expansion of transit service, Los Angeles traffic is worse. The multiple rail lines completed have failed to reduce traffic congestion, as transit ridership has experienced a “reverse boom,” unlike the building boom referred to by The Times. In calendar year 2017, there were 100 million fewer MTA bus and rail riders than rode SCRTD, then only with buses, the year of the 1984 Olympics (fiscal year 1984-5).

But there have been roadway capacity and operational improvements. The latest American Community Survey data shows that drivers still travel less than 30 minutes one-way to work, the shortest work trip travel time reported for any of the world’s megacities (over 10 million population). Companies can still make short term arrangements to reduce traffic. And MTA still has buses. There is every reason to believe that Los Angeles companies, planners and elected officials have the capacity, much enhanced by the digital revolution, to meet whatever challenge arises in facilitating access to the 2028 Olympics, with or without the Purple Line.

Finally, it is hard to imagine a program that makes a better case for cutting that federal new starts. Huge expenditures have been spent to build new rail lines (and some exclusive busways) around the country in the last four decades. Yet, driving continues to increase. Among 23 metropolitan areas adding new rail lines, there was a small loss in transit’s market share (0.4 percent), while driving alone increased 3.7 percent. Los Angeles, which suffered by far the largest transit drop since 2014, some 16.6 percent, epitomizes these trends.

Yet, one of the principal justifications for these systems was to attract drivers out of their cars. That objective has not been met and there is no reason to believe it will be in the future. It would be better to use available funds for improvements that are likely to serve passengers better, both before and during the Olympics.

Note: During this period, I was one of three city of Los Angeles representatives on the Los Angeles County Transportation Commission (the policy predecessor to today’s Metro), having been appointed by Mayor Tom Bradley. I opposed the SCRTD Olympics bus plan, and expressed concern that it would leave taxpayers “holding the bag” for a deficit of at least $5 million. SCRTD had projected that revenues would equal costs. In the end, the deficit was slightly less than I expected ($4.7 million). Actual ridership fell 63 percent short of SCRTD’s projections, a figure that mirrors the persistence of overly optimistic ridership projections for both transit and high speed rail around the world. I had objected to the service on a number of occasions and at my farewell reception a few months later, the SCRTD President, in good humor, presented me with a set of SCRTD commemorative Olympic coins. But on balance, the SCRTD Olympics loss was small compared to the billions that have been spent since that time only to see ridership drop by a fifth.

Wendell Cox is principal of Demographia, an international public policy and demographics firm. He is a Senior Fellow of the Center for Opportunity Urbanism (US), Senior Fellow for Housing Affordability and Municipal Policy for the Frontier Centre for Public Policy (Canada), and a member of the Board of Advisors of the Center for Demographics and Policy at Chapman University (California). He is co-author of the "Demographia International Housing Affordability Survey" and author of "Demographia World Urban Areas" and "War on the Dream: How Anti-Sprawl Policy Threatens the Quality of Life." He was appointed to three terms on the Los Angeles County Transportation Commission, where he served with the leading city and county leadership as the only non-elected member. He served as a visiting professor at the Conservatoire National des Arts et Metiers, a national university in Paris.

Photograph: SCRTD bus in front of the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum, August 3, 1984 photo

Courtesy of the Metro Transportation Library and Archive on Flickr. It was used under a Creative Commons License.