Is Europe a museum of old success? The question is topical, as Europe's population will peak in two years and is then expected to decline for the rest of the century. During the roughly three decades that have passed, Europe has also fallen behind North America economically. However, Europe is not yet a museum of old success, as Stockholm, London, Paris, Amsterdam, Dublin are among the world's leading centers for the development of deeptech. Sweden, Ireland, the UK and other European nations need to continue to be at the technological forefront, to avoid stagnation at a time when the emerging economies in Asia are catching up.

As late as 1990, the current EU countries and North America together constituted a clear majority of 55 percent of the world's global economic output. In connection with the financial crisis in 2008, it fell to less than half of the world economy. As the rest of the world has caught up, the percentage is now 42 percent.

It is not surprising that the roughly one billion people living in North America and Europe no longer make up half the world economy. In this regard, a process of normalization has taken place, in connection with the spread of the market economy to more countries, which have been integrated into global trade and have grown economically. What is remarkable is that North America, which already accounted for a larger share of the world's economic output just over 30 years ago, has maintained its relative position significantly better than the EU.

Even in terms of population, the US and North America as a whole are growing, while the existing challenges with an aging population in Europe are getting worse according to new forecasts. According to Eurostat's latest analyses, the EU's population is expected to reach its peak as early as 2026, and then gradually decrease. While the UK and a few other countries have more positive growth during coming decades, for Europe as a whole the trend is clear. During the rest of the century, there will be fewer inhabitants, but more elderly people, in Europe year after year. In order to avoid economic stagnation, it is required that Europe at least maintains its technological leadership.

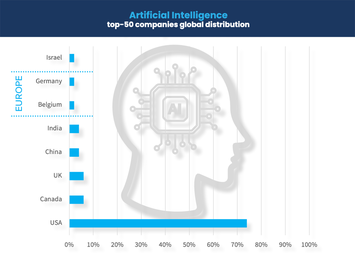

In the new Deep Tech Index, launched by the European Center for Entrepreneurship and Policy Reform (ECEPR), with support of Nordic Capital, the 500 leading deep-tech companies in the world are mapped out. A strong lead for North America relative to Europe is clearly evident when it comes to the development of cutting-edge technology. Despite that, Europe is not a museum of old success, because the lead over the rest of the world is still clear. There are more world leading deep tech companies in Europe than Asia.

The leading deep tech hubs outside the US are London, Tel Aviv, New Delhi, Toronto, Paris, Tokyo, Bengaluru, Amsterdam, Berlin, Stockholm, Montreal and Dublin. Many of them are in fact in Europe.

The countries with a high concentration of deep tech companies per million adults have strong private property protection, lower taxes as a share of total economic output, good school results in PISA, and a high proportion of world-leading colleges of engineering and technology per million adults.

School results according to PISA are plummeting in high-tax countries such as Sweden and Finland, but are stronger in Ireland and Estonia, European nations with limited taxation. Where individuals have stronger incentives to gaining education, growth is occurring.

According to the QS World University Rankings, 30 of the hundred leading universities in engineering and technology are in Europe, slightly more than 27 in North America and just behind 34 in Asia. It is true that the US benefits from attracting the sharpest minds, but again it is European politics that through high taxes push out talents. The UK is the leading higher learnings hub of Europe, with fully 7 out of the leading global universities. European nations need to focus better on fostering top universities, with the UK being the most successful nation to emulate in this regard.

Europe is not a museum of old success. Yet it is falling behind with policies focused on preserving old prosperity, not creating new economic values. The international connection is that the presence of one additional leading deep tech company per million adults is linked to 1.26 percentage points lower unemployment in that country. There are clear economic benefits associated with succeeding in technological progress, for the labor market and the level of prosperity. Ultimately it is about a Europe that is growing, or stagnating.

Development does not come by itself. Economic policy and education policy are needed that focus on future prosperity. A growth mentality is required for Europe to remain in the technological edge. Taxes need to be reduced, private property rights protection strengthened, school results improved, and top technological universities need more funding.

When for example a firm stagnates, this may create a reaction to preserve the old economic values, for example keep the old business model at any cost, instead of looking on how to again become profitable. The same goes for Europe, governments regulate and give grants, to protect the old – while doing so stifle new progress. This instinct, for long dominant in countries such as France, is spreading. There are clear signs of Europe moving towards polices of stagnation, for example the UK has shifted towards more regulation and higher taxation lately. Smaller European nations such as Ireland and Malta, with competitive taxation, are leading the way. Ireland, which has a factor ten higher population of the two, is also a strong hub of deep tech.

Europe as a whole should learn more to embrace new creation, becoming a museum of past success is not a given development. But as Europe in a couple of years from now is expected to stagnate population wise for the remainder of the century, it is worth focusing on what it takes to remain vibrant while the population is shrinking. Remaining on top of technological development really is the key challenge because that has been Europe’s bread and butter since it become world technology leader during the renaissance.

Nima Sanandaji, Director, European Centre for Entrepreneurship and Policy Reform (ECEPR)

Chart: courtesy Nima Sanandaji