From public forums to mobility conferences to office watercoolers, dockless electric scooters (“e-scooters”) are a hot topic these days. Travelers are turning to e-scooters to shave precious time off their commutes and experience urban environments in fun new ways. City officials, meanwhile, are asking difficult questions about their safety and impacts on sidewalk use and transit.

Despite all the attention being given to this “micro mode” of travel, remarkably little analysis exists about its potential transportation role. Typically, traveling by e-scooter tends to be a bit slower than bicycling; however, e-scooters have a smaller footprint, and can be made available in more places, making them less geographically constrained than traditional “bikeshare” systems. Furthermore, unlike dock-based bikeshare systems (like Chicago’s Divvy), e-scooters available for “sharing” are usually free-floating and thus do not need to be returned to a docking station. This can result in a significant time-saving advantage.

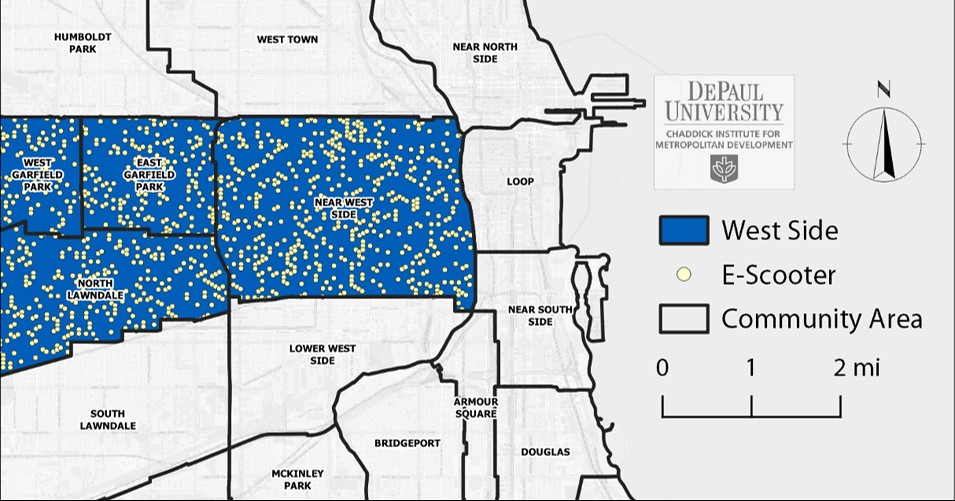

Figure 1: Scooters randomly distributed on the West side of Chicago

This image shows the random assignment of scooters in our mobility model in the West Side study area of Chicago.

Amid all the hubbub about e-scooters, however, basic questions about their transportation role remain unanswered. Will e-scooters encourage more urban residents to avoid car ownership? Are they cost effective for the typical commuter? Are e-scooters mostly a complement to—or substitute for—urban transit systems?

To help answer these questions, we developed a “multimodal mobility model” to see how e-scooters stack up against the competition. We compared how travel times change under hypothetical scenarios in which e-scooters are randomly distributed throughout a neighborhood (Figure 1). Our new study measures how e-scooters performed on trips between approximately 30,000 randomly generated locations on the North, South, and West sides of Chicago.

But first, a disclaimer: we received financial support for the study from Bird, the Santa Monica-based e-scooter company, which operates in many cities and has an interest in serving Chicago. This support allowed us to evaluate e-scootering as both a stand-alone mode of travel and a “last mile/first mile” solution involving connections to buses and trains.

Based on our model, several findings stand out:

1. In neighborhoods just outside of downtown, the “sweet spot” for e-scooter trips is between 0.5 – 2 miles. E-scooters fill a void for trips at these distances, which are often too long to comfortably walk but too short for transit. When taking a bus or train, travelers often spend more time walking and waiting than on a transit vehicle.

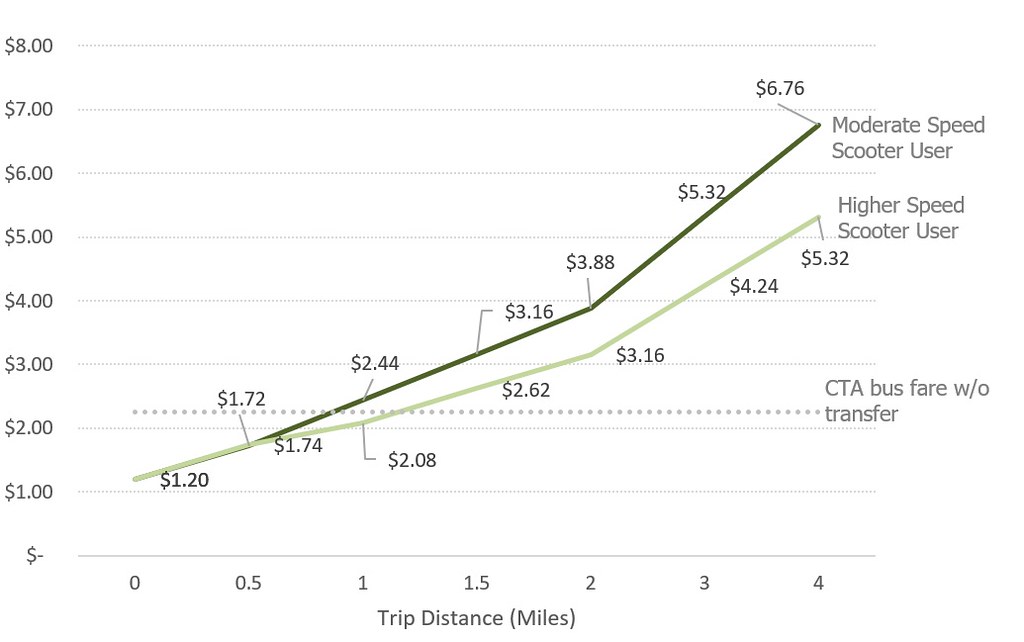

At these distances, e-scootering is generally faster than dock-based bikesharing due to the ability to access a vehicle quicker and drop it off directly at one’s destination without the hassle of finding an open dock at a bikeshare station. Ridehailing services, such Lyft and Uber, conversely, have their own problems, with wait times and per-mile costs that are at least twice that of scooters. On trips under one-half mile, though, finding a scooter and paying the fee (generally, $1 plus $.15 per minute, not including taxes) often makes them not worth the trouble.

2. For short-hop trips in areas in which travelers must search for parking or spend time accessing parking garages, e-scooters can be as fast—or faster—than driving. Based on our model, when a traveler spends three minutes at each end of her trip searching for and accessing (and paying for!) parking, e-scooters can get her to the same place within two minutes of driving on three-quarters of trips in the 0.5-2 mile range. For this reason, we think that e-scooters have the potential to help foster car-free urban living.

3. Due to their cost on trips over three miles, e-scooters would likely not be a major factor on medium- and long-distance journeys. The appeal of e-scootering drops off sharply when traveling more than a couple of miles. Not only are they typically slower than using bikesharing at these distances, but the costs can exceed $5 or $6 per trip, putting them out of reach for many. On these longer journeys, e-scooters are often best used on short hops to neighborhood transit stops.

Figure 2: Expected Average Price of Using Shared E-Scooter, Inclusive of 10.25% City Tax

Short e-scooter trips are often less than transit fare. Longer trips made at moderate speed (7.5 mph average) rises to levels more than $5.

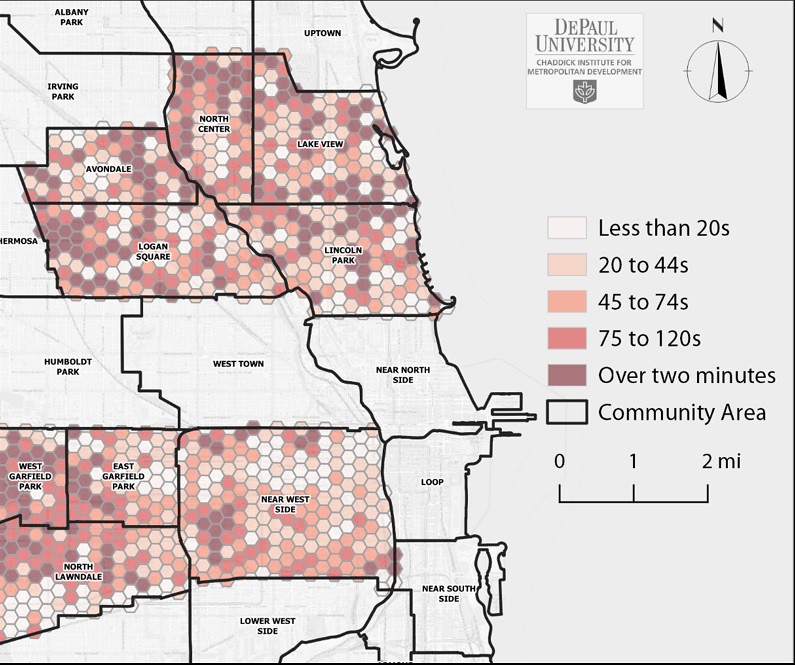

4. The benefits of e-scooters can differ widely between geographic areas that are only a few blocks apart. This is the result of the often-spotty nature of transit lines and bikeshare stations, which we found to be particularly problematic on Chicago’s South Side. The average time saving on trips to downtown Chicago (compared to bikesharing and transit) varies from zero to three minutes in the same neighborhood (Figure 3). But the net effect, we find, is that e-scooters would make 16% more jobs reachable within 30 minutes compared to those currently accessible by other non-auto modes.

Figure 3: Average Time Savings from the Introduction of E-Scooters on trips to Downtown Chicago

The estimated average time saving for downtown travel compared to docked bikeshare and transit resulting from the introduction of e-scooters varies sharply within the same neighborhood.

A complete analysis of e-scooters, of course, requires consideration of a wider range of issues, such as aesthetics, safety and sidewalk clutter, none of which are considered in our study. Cities certainly have their hands full assessing all the difficult tradeoffs. But from a mobility perspective, e-scooters appear destined for a promising future – if they can navigate the regulatory speedbumps along the way.

Joseph Schwieterman, Ph.D., is director of the Chaddick Institute for Metropolitan Development at DePaul University in Chicago. C. Scott Smith, Ph.D., serves as the institute’s assistant director. Their study E-Scooter Scenarios was released last week.