Many public transit agencies are struggling to sustain lightly-used routes as passenger traffic dips in response to relatively cheap automobile fill-ups, a rise in work-from-home lifestyles, and the growing popularity of transportation network companies (TNCs), such as Lyft and Uber. The brunt of the decline has been sharpest in small and mid-size communities, where some bus services are infrequent, follow meandering routes, and stop running after peak hours.

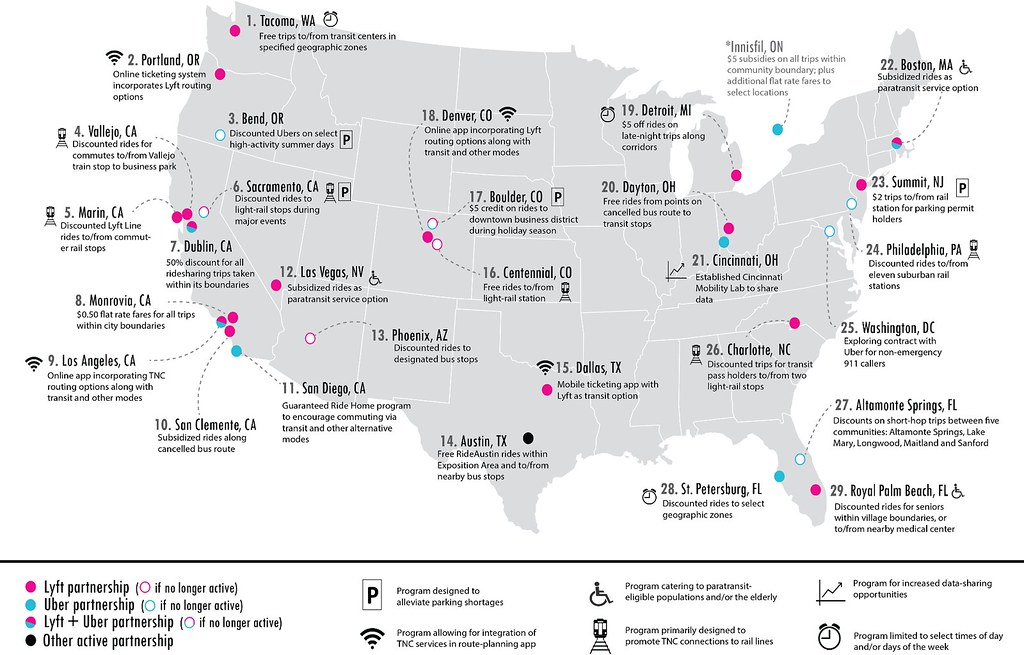

Facing growing pressure to try new things, many transit agencies and municipal governments are experimenting with strategies that involve ridesharing. Our new study, Partners in Transit: A Review of Partnerships between Transportation Network Companies and Public Agencies, describes more than two dozen partnerships around the country designed to allow transit operators and TNCs (predominately Lyft and Uber) to concentrate on what they do best. TNCs fill gaps, offer “first- and last-mile” solutions, and augment service to those with mobility challenges, while transit providers direct resources to modernizing top-performing routes, serving commuters, and other core strengths.

The idea behind many partnerships is that a properly designed program can be less expensive than buying buses and paying for labor, fuel, and maintenance on lightly used routes. They also give public bodies experience with emerging technologies and can boost the public image of transit, not to mention get travelers to their destination faster. The pace at which partnerships are emerging across the country deserves far more attention than it has received.

Several of the most intriguing partnerships provide all travelers free or discounted ridesharing trips within a community. Monrovia, CA’s partnership subsidizes Lyft rides so that travelers can go between any two points within its boundaries cost just $0.50. Since the program’s introduction in March, more than 53,000 trips have been taken at this ultra-low rate, which city officials believe boosts mobility, alleviates parking shortages, and enhances economic development.

Dublin, CA offers across-the-board 50% discounts of up to $5 on all Uber and Lyft trips within its boundaries, including those shuttling to its Bay Area Rapid Transit station. Across the Canadian border, Innsifil, Ontario—reportedly Uber’s first program in that country—boasts a similar discount program and has generated an outsized amount of publicity.

But more narrowly focused programs, such Dayton, OH’s and San Clemente, CA’s, which limit most rideshare discounts to areas affected by service cuts, are especially “hot”. Austin, TX’s program offers free trips provided by RideAustin within its Exposition Area, which has many technology jobs, as well as trips to/from nearby bus stops. Charlotte, NC, Summit, NJ, and Marin County, CA have improved access to new rail-transit lines and have mitigated parking shortages by offering discounted rides to certain stations. In Detroit, MI and the St. Petersburg, FL area, there are special discounts for night-shift workers.

The process is simple: customers usually enter a discount code into an app to receive the fare reduction, and government agencies pay the difference, which is often $4 - $8 per ride—well below the cost of moving the same customers on buses or trains. Nevertheless, making these programs permanent can be tricky: if programs are too generous, they can become victims of their own success, outstripping the budget; if too stingy, they generate little “buzz” and go largely unused.

Still, both large and small agencies are testing the waters: 11 of the 50 largest transit agencies in the United States have experimented with some form of partnership. If more major players make the plunge, there will likely be “strings attached” for users, due to the obvious problem that a poorly designed program could cannibalize bus and train ridership. Agencies in Boston and Las Vegas, for example, have created programs limited primarily to paratransit-eligible users to manage that risk. Boston’s program appears to involve the greatest ridership of any partnership created to date.

What comes next? Being able to pay for both rideshares and transit – and connections between the two – on a single app. Up until now, customers must buy pay two fares when making ridesharing/transit connections. This inconvenience will end once sensitive issues such as protecting private information and technological hurdles can be crossed.

Considering the speed at which ridesharing is growing, more agencies will likely reach out to Lyft, Uber and other providers to test out new strategies in the next couple years.

Joseph Schwieterman, Ph.D., is professor of Public Services and director of the Chaddick Institute for Metropolitan Development at DePaul University in Chicago. His co-authored study Partners in Transit was released last week.

Top photo: A Miamisburg, Ohio bus stop, part of the Dayton area’s free Lyft-ride program for areas affected by service cuts. Photo source: J. Schwieterman